Staring at a Blank Sheet of Paper Write

advertisement

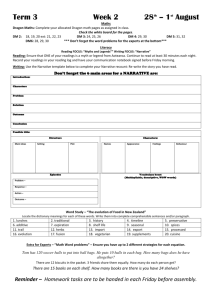

Kristin Runyon EIWP 2012 Demo Lesson Staring at a Blank Sheet of Paper Rationale: Gretchen Berabei states: “Some writers would be able to take off with [the instructions for an essay or narrative] and no further assistance. Other writers (including most writers in my classes) appreciate a step-by-step process, at least until they become confident and inventive. Breaking down a complex process into concrete steps is the craft, the fun of teaching. For essay [or any writing], these steps can work:” (Teaching the Neglected “R” 75) 1. Decide what to say. 2. Design a structure. 3. Flesh it out Additionally, Dolores Perin and Steve Graham analyzed research-based recommendations for adolescent writing instruction and organized them from #1-11 based on their effect. #1. Strategy Instruction—Teach adolescents strategies for planning, revising, and editing their compositions. (Best Practices 248) #3. Peer Assistance—Develop instructional arrangements where adolescents work together to plan, draft, revise, and edit their compositions. (250) #4. Setting Product Goals—Set clear and specific goals for what adolescents are to accomplish with their writing product. (251) #9. Prewriting—Engage adolescents in activities that help them gather and organize ideas for their compositions before they write a first draft. (255) Learning Standards: The Common Core Standards require that students at ALL grade levels (kindergarten through 12th grade) write three types of compositions/essay each year: 1) Opinion (K-5)/Argumentative (6-12) 2) Informative or Explanatory 3) Narrative Preparation: Copies of Prewriting Topic Bank on colored paper (to be kept and added to all year) Copies of Round Robin Elements of Literature to be included in final draft of story Activity for Prewriting Topic Bank: As one of the start of the school year activities, my students will complete the Topic Bank foursquare to keep handy for writing assignments throughout the school year. For the personal narrative assignment, if a student is struggling to find a topic, I would have him/her complete the Decide What to Say series of questions. Activities for Writing a Round Robin Creative Narrative: Have students sit in groups of 3, 4, or 5 students (depending on your age group and number of students in class). Review the elements of literature plot map. Explain to the class that each student will be creating a story but only in stages. Each student will start a story, writing the EXPOSITION—setting (time and place), characters, and conflict. After a few minutes of writing (3-5 minutes), students will pass their expositions to the next person in the group. Each student will read the exposition and then write the RISING ACTION—all the events leading up to the but NOT including the climax—using the setting, characters and conflict created by the original author. After a few minutes (5-7 minutes; you will need to give extra time for the reading), students need to pass to the next person in the group. Each student will need to read the new exposition and rising action and write the CLIMAX. After a few minutes of reading and writing (5-10 minutes), students need to pass to the next person in the group. (If using groups of three students, each student should be receiving his/her original exposition.) Each student will need to read the exposition, rising action, and climax and then write the FALLING ACTION and RESOLUTION. (If using groups of five students, have them only write the falling action in this step and then have person #5 write the resolution). After a few minutes of reading and writing (7-10 minutes), students should pass the narrative to the student who wrote the exposition. After reading their completed stories, students may choose to share with the group. Activities for Editing and Revising Round Robin Short Stories: Students may choose which story to edit and revise; they do not need to stick with the narrative in which they wrote the exposition. If more than one student wants to revise the same story, photocopy the story so that each student has a copy. I allowed students to delete two details (not two sections) from his/her story. For example, one student in a group introduced aliens into each story, but not every student wanted aliens in his/her story. Provide students with Round Robin Elements of Literature Narrative handout. Students need to revise to include all the listed elements of literature. The handout is created so that the students list each element as it is included in the narrative. This strategy helps the students to keep track of the required elements. Have the students peer edit the narratives; I would suggest having a student who did NOT help write the narrative. The peer editor could also complete a new copy of the elements handout. Assessment: Both the original narrative and the revised narrative should be turned in. The revised narrative should be graded for the successful inclusion of the required elements. Adaptations and Modifications: Students could revise in partners. In content areas, before or after writing the initial round robin story, students could be required to include historical figures or events, vocabulary words, or scientific processes to prove understanding of the current unit. To practice prediction skills, the teacher could read the exposition to a story and have students write an individual narrative (rising action, conflict, resolution) predicting what could happen. Students should write explaining what details in the exposition made them choose the events in the rising action/conflict/resolution. The teacher should then read the remainder of the story so that students hear the original version (students should not be penalized for having different versions but should be graded on the use of prediction skills). References: Best Practices in Writing Instruction. Eds. Steve Graham, Charles A. MacArthur, and Jill Fitzgerald. New York: The Guilford Press, 2007. Print. Teaching the Neglected “R”: Rethinking Writing Instruction in Secondary Classrooms. Eds. Thomas Newkirk and Richard Kent. Portsmouth, NH: Heineman, 2007. Print. Topic Bank by Ralph Fletcher and JoAnn Portalupi I am an expert at: I will always remember: I feel deeply/strongly about: Life lessons that I have learned: “Decide What to Say” by Gretchen Bernabei 1-3: Write down words or phrases which remind you of moments in your life you were proud of someone. 4-6: Write down moments in your life when you had to struggle in some way. 7-9: List memories in addition to the first six that you’d like to keep if a dystopian government (robot) were erasing your memory tomorrow. 10: Write down a memory involving an animal. 11: Write down a memory involving a gift you gave someone. 12: Write down a time someone gave you money, any money—a nickel, a dollar, a check. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12.