ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ ᡤᠢᠰᡠᠨ

advertisement

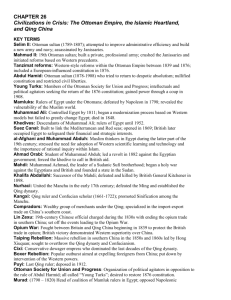

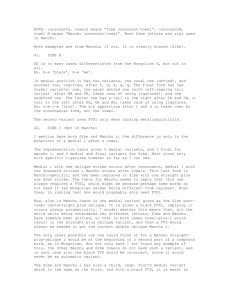

Language of the Month: Manchu By Naoki Watanabe (ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ ᠸᠠᠬᠠᠣ/Manju Gisun) When you think of Chinese history, what language first comes to your mind? Most of you would probably think of Mandarin or other forms of Chinese like Hakka, Cantonese, or Dungun. A few of you may think of non-Chinese languages spoken by ethnicities that at one point or another ruled vast amounts of or even all of present day China’s territory. These languages include Mongolian (which was official in the times of the Yuan Dynasty), Uyghur (in the areas of the Uyghur Khaganate), Oirat/Kalmyk (in the former Dzungarian Khanate), Tibetan (in Tibet), and many others. However, not many of you may think of Manchu. The Manchu language is the best known and arguably the most widely spoken of the Tungusic languages. These languages are native to Manchuria and many parts of Northeastern Asia as well as a small pocket in Xinjiang (where Xibe is spoken). Apart from Manchu, other languages in this family include Xibe (spoken in Qapqal), Evenki (spoken in Siberia, Northern Mongolia, and Manchuria), Nanai (spoken in Siberia), the extinct Jurchen language (spoken by the Jurchens—the ancestors of the Manchus), and Orok (which is spoken in Sakhalin and Hokkaido). When most people think of the Yuan Dynasty, the image of Kublai Khan and his Mongol warriors administering China and speaking Mongolian often comes to mind. However, when most people think of China’s last and most powerful dynasty—the Qing—most people just assume that the rulers were Chinese and spoke Chinese. This, however, is not the case as the Qing Dynasty was established and ruled by a Tungusic ethnic group known as the Manchus who come from the region of Manchuria (which today consists of the Chinese provinces of Heilongjiang, Liaoning, Jilin, and a part of Inner Mongolia). The Manchus initially spoke a language known as Jurchen which was developed into Manchu after Nurhaci ordered the creation of the Manchu script (which is derived from the Mongolian alphabet). The Manchus were initially quite protective of their language and continued to use it for administrative purposes after their conquest of China as the Qing Dynasty. However, as time passed, the Manchus gradually lost proficiency in their language due to the overwhelming influence of Chinese since Manchus only made up about 2% of their empire’s population. This was worsened by mass Chinese immigration to Manchuria in the 19th Century which resulted in the Manchus becoming a minority in their own homeland and Mandarin eventually becoming the dominant language of the region and the natives. Nowadays, Manchu is on the verge of extinction as a native language with the number of native speakers being between 18 and 70 and all of them being elderly Manchus living in isolated villages in Heilongjiang. Moreover, out of 10 million ethnic Manchus, only about a million have some ability in the language. However, there is an active movement amongst Manchus in recent years to revive their language and due to the abundance of resources as well as the circumstances of the language, revival is a possibility. The once completely extinct Hebrew language was revived in Israel due to the availability of resources on the language and due to its centuries-old use amongst Jews as a liturgical language. Manchu is in an even better position due to the massive amounts of Qing Dynasty-era archives and textbooks that were written in the language and also due to the existence of the Xibe people. The Xibe are a Tungusic people who speak a language that has many similarities to Manchu (to the point that Xibe is considered by some linguists, such as Jerry Norman, to be a dialect of Manchu) who were sent to garrison the area of Qapqal in Xinjiang. Due to their isolation, about 40,000 Xibe still speak their language and many Manchus have been travelling to Qapqal with the intent of learning Xibe and then using their knowledge of the language to aid in teaching themselves Manchu. In addition to the Xibe people, the revival of Manchu is aided by the existence of several autonomous counties in Manchuria which sometimes contain schools where Manchu is taught as an elective. If a Japanese person were to study Manchu, he/she would find two things to be incredibly easy: pronunciation and grammar. Tungusic languages in general have similar sounds to Japanese and Korean due to centuries of historical contact and possible linguistic relations and this makes it easy for Japanese people to pronounce them. For the same reason, the grammar is also similar. An example of this can be seen in the sentence ᠪᠢ ᠣᠴᠢ ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ ᡤᡠᠷᡠᠨ ᡳ ᠨᠢᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠ ᠃ (bi oci manju gurun i niyalma)—I am a person of Manchuria (“manju” means Manchu while “gurun” means country or empire). The word “bi” means “I” while the word “oci” is analogous to the Japanese は or が. The word “i” is analogous to the Japanese の while “niyalma” here means person but can also be used as a race or ethnicity (much like the Japanese 人). Another similarity in grammar can be -ᠮᠪᠢ -mbi which is used in the same way as the Japanese ます, する, or だ. Verbs such as ᡤᠢᠰᠨᠷᡠᠡᠮᠪᠢ “gisurembi” (to drink) ᡥᠠᠢᠷᡠᠠᠮᠪᠢ “hairambi” (to love) and ᠣᠮᠢᠮᠪᠢ “omimbi” (to drink) can be seen in the way verbs end. Manchu verbs almost always end with directly translated into Japanese as 話します, 愛する, and 飲みます, respectively. Despite these aspects of the language being relatively easy for Japanese people, there are also several difficulties. The most notable one is the script as the Manchu script is somewhat difficult for people who aren’t used to writing systems derived from the Mongolian script (such as Todo Bichig and the Xibe alphabet). The Manchu script is very similar to the Mongolian alphabet as it was created under the orders of Nurhaci when he proposed modifying the Mongolian script with symbols to represent sounds in Manchu that don’t exist in Mongolian. The script is written from top to bottom with lines following from left to right in most cases and with commas being marked by a dot and periods being marked with two dots. Apart from the script, another difficulty is in the transliteration of Manchu as several systems exist. However, the most widely used and wellknown system for transcribing Manchu is the one created by German diplomat Paul Georg von Möllendorff. The Möllendorff System, as it is called, uses Roman letters in the same way they’re used in English with a few exceptions. These exceptions are The Manchu alphabet. Note that it can also be used like the Roman Alphabet the use of the letter c to represent the “ch” sound, the use of x to represent the “sh” sound, and the use of the letter v to represent the long “u” sound (ū). Additionally, the letter w is sometimes read with a v sound and there are also 10 characters of the Manchu alphabet that exist specifically to transcribe Chinese words. One of the peculiarities of studying Manchu is that study materials are relatively easy to come across if you look for them. This is in spite of the fact that Manchu speakers are incredibly difficult to find and opportunities to use the language (outside of Manchuria or Qing Dynasty research circles) are very limited. In my opinion, the best resource in existence is Manchu: A Textbook For Reading Documents by Gertraude Roth Li as this book not only contains details on Manchu grammar, pronunciation, script, and mannerisms, it also contains historical records in the form of reading samples written in Manchu, an account of the Manchu conquest of Dzungaria (and how this contributed to the survival of Xibe) and even reading samples and guides on Xibe. Other noteworthy resources are A Manchu Grammar, With Analysed Texts by Paul Georg von Möllendorff, the Manchu textbook available on Wikibooks, and A Comprehensive Manchu-English Dictionary by Jerry Norman. Another noteworthy resource is the South Korean movie War of the Arrows by Kim Han-min. Set during the Manchu invasion of Korea in 1636, the actors portraying Manchu characters in the movie speak Manchu throughout the movie. Manchu is overall mostly studied for two reasons: to be used as a tool in research on Qing Dynasty history and to be studied as part of the movement to revive the language amongst ethnic Manchus. Either way, I believe Manchu is a language that’s worth studying. Not only is it the most prominent member of the Tungusic language family (as it was the only one to be used in an empire), Manchu has been incredibly influential to China’s history and it would be a shame if it became extinct. Furthermore, for those of you who’re going to Okinawa for the school trip, be sure to look for the Manchu stamps available at the gift shop in Shuri castle (Manchu stamps were used by the Ryuukyuu Kingdom in their relations with the Qing Dynasty). Phrase List English Manchu/ ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ Hello hojo na ᡥᠣᠵᠣ Thank You baniha ᠪᠠᠨᠢᡥᠠ You’re Welcome ume manggaxara ᡠᠮᠡ Excuse me xinde fonjiki ᡧᠢᠨᡩᠡ Where is the toilet? abade bi edun karanara? Goodbye sirame acaki ᠰᠢᠷᡠᠠᠮᠡ My name is…. mini gebu oci __ ᠮᠢᠨᠢ Can you speak Manchu? ᠨᠠ inggiri Japanese ziben Chinese nikan 1 Emu ᠡᠮᡠ 2 Juwe ᠵᠨᠸᠡ 3 Ilan ᠢᠯᠠ 4 Duin ᡩᠨᠢ 5 Sunja ᠰᠨᠨᠵᠠ ᠮᠠᠨᡤᡤᠠᡧᠠᠷᡠᠠ ᡫᠣᠨᠵᠢᠬᠢ ᠠᠪᠠᡩᠡ ᠪᠢ ᠡᡩᠨ ᠬᠠᠷᡠᠠᠨᠠᠷᡠᠠ ᠃ ᠠᠴᠠᠬᠢ ᡤᠡᠪᡠ ᠣᠴᠢ ___ si oci manju gisurembio? ᠰᠢ English Happy Birthday ᡤᠢᠰᠨ ᠢᠨᡤᡤᠢᠷᡠᠢ ᡰᠢᠪᠡ ᠨᠢᠬᠠ banjiha arambi ᠪᠠᠨᠵᠢᡥᠠ ᠠᠷᡠᠠᠮᠪᠢ ᠣᠴᠢ ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ ᡤᠢᠰᠨᠷᡠᠡᠮᠪᠢᠣ᠃