Click here to get the file

advertisement

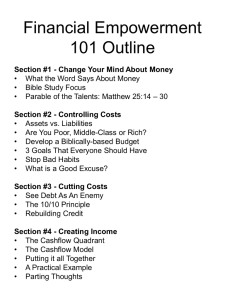

2nd SUNDAY BEFORE ADVENT 2014 (Proper 28A) HC 16-11-14 Do you recall Donald Rumsfeld, the American Secretary of Defence to Presidents Ford and George W Bush? One of the things I remember him for is this saying: “...as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns -- the ones we don't know we don't know. And ... it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.” Let’s apply a version of ‘Rumsfeld’s Law’ to scripture. Sometimes the readings we hear on a Sunday seem straightforward, and sometimes they seem obscure. When they’re straightforward we think we understand them, and when they’re obscure we know we don’t understand them. The trouble is, there are times when we think they’re straightforward and we understand them, but that’s only because we don’t know enough to realise that we don’t understand them! So I wonder whether there’s anything we don’t know we don’t know in the gospel reading about the talents? First of all, of course, what we’ve had read out today contains a sleight of hand. We began to read from chapter 25 at verse 14: ‘The Kingdom of Heaven is as if...’. Actually, the words of that verse start ‘It is as if...’, but those who chop scripture up into bite-sized pieces for public reading have decided that the ‘It’ refers back to verse one of the chapter, the words that introduce the parable about the wise and foolish virgins. Jesus says of that, ‘The Kingdom of Heaven is as if...’. Lectionary compilers, having decided that we need a few words to put today’s reading in context, have seized on those words. But have they got it right? You see – and this might be something we didn’t know we didn’t know – a lot of scholars think that the ‘It is as if’ actually opens up a whole new line of thought to do with those who ‘know neither the day nor the hour’ of the coming of the Kingdom. And here’s an important bit of evidence: in St Luke’s Gospel Jesus tells the same story introduced by the words, ‘He went on to tell a parable, because he was near Jerusalem, and because they supposed that the Kingdom of God was to appear immediately’ – Luke uses it as a caution against thinking the Kingdom is coming immediately, just as Matthew leads into it by using the end of the parable of the wise and foolish virgins to say ‘you know neither the day nor the hour.’ So is it simply about how to live ordinary life while we wait? Seen this way, it isn’t a Kingdom parable but, rather, a Wisdom parable. Now you might think this is all of academic interest but of no practical use whatsoever. Except that there’s more. A hundred stewardship sermons and religious reflections have taught us that this is a parable about working hard and using the talents that God has given us (and the sin of not using them), so that those who do that are rewarded and those who don’t are punished. But suppose that this parable of the talents actually is simply a Wisdom parable about how to survive in this world, rather than a Kingdom parable about how to live out the life of heaven; that it’s about ‘how do I get along in the current situation’ rather than ‘what is my vocation as an agent of God’s Kingdom.’ Let’s say, for today, that it is; and so let’s unpack it with that in mind for once. When we do that, the servant who buries the talent comes out rather differently. So how might this parable have sounded to the Jewish peasants who were Jesus’ followers, rather than it does to us who have been conditioned to read it in a western, capitalist, individualistic way (because that’s the world of assumptions that we’ve been born into)? For one thing, they would have been well aware that it was against the Law of Moses to charge interest; and for another, that when the 12 tribes entered the Promised Land the ‘promise’ was that every family would receive and hold a share of the land forever. Those who had become rich had become rich by acquiring land that belonged to others – the master in the parable admits this when he says that ‘I reap where I did not sow, and gather where I did not scatter’ (verse 26). In other words, he got rich (effectively) by stealing from others. So, viewed from the perspective of Jesus’ Jewish hearers, the slave who buried his master’s talent was doing an honourable thing. He was not using the wealth proactively to cheat or to steal even more, nor was he breaking God’s law by using it passively to earn interest. He was simply acting as honourably as he could in the situation, preserving the wealth of another that had unfortunately been entrusted to his care, but washing his hands of any further business with it. The servant does nothing to harm anyone, but through a (later) publicly revealed act he makes clear his refusal to participate in an unjust system in which the few become wealthy by impoverishing the many. It’s an act of passive resistance in which a person of no account, with little power, refuses to be drawn into the game played by the wealthy elite. To have put the ill-gotten wealth to work, or to have invested it, would have been to make himself no better than his unrighteous master; it would have been positively to declare himself as his master’s man, rather in the way that criminal gangs bind weak fringe members into the gang by forcing them to commit some crime so that they are tarred by the same brush. But he refuses to be drawn in. No wonder his master has such harsh words for him. It’s highly ironical – on this reading at least – that the master’s words to the servant have been taken by the Church to be Jesus’ words, and have been used to support the very practices that the parable condemns. Well, I’ve laid out an alternative reading of the story; a way of understanding it in its 1st century Jewish context that maybe we didn’t know we didn’t know. And in the context of the early Church, with Christians living lives immersed in all the ambiguities and difficulties and dangers of a multi-cultural world to which the long-awaited Christ hadn’t returned, it was perhaps simply a message about how to survive. ‘You’ll be expected to do things that you don’t agree with – find ways of not doing them. You could just sell your principles and go along with it all and get rewarded and congratulated. But the faithful servant – the truly faithful servant, servant to God and not to Mammon – finds ways of not going along with it.’ In all the ambiguities and temptations of our own society that might be a message for us as well. The Kingdom of God is known among us not just in heroic lives of sacrifice and courageous faith and love, but in a million small acts of rebellion, made by unsung men and women – perhaps even by you and by me -- of not following the way of the world, and of preserving our integrity and honour thereby. That too has its place in the teaching of our Lord Jesus Christ. Christopher Pullin, 16-11-14