Getting along across Cultures

advertisement

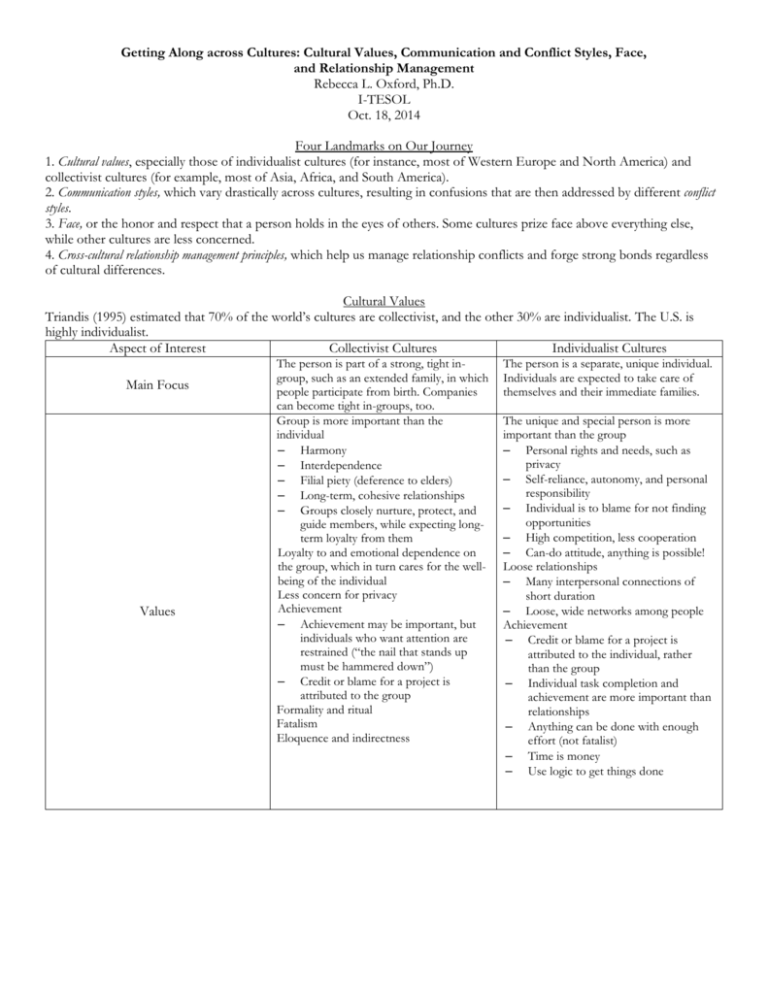

Getting Along across Cultures: Cultural Values, Communication and Conflict Styles, Face, and Relationship Management Rebecca L. Oxford, Ph.D. I-TESOL Oct. 18, 2014 Four Landmarks on Our Journey 1. Cultural values, especially those of individualist cultures (for instance, most of Western Europe and North America) and collectivist cultures (for example, most of Asia, Africa, and South America). 2. Communication styles, which vary drastically across cultures, resulting in confusions that are then addressed by different conflict styles. 3. Face, or the honor and respect that a person holds in the eyes of others. Some cultures prize face above everything else, while other cultures are less concerned. 4. Cross-cultural relationship management principles, which help us manage relationship conflicts and forge strong bonds regardless of cultural differences. Cultural Values Triandis (1995) estimated that 70% of the world’s cultures are collectivist, and the other 30% are individualist. The U.S. is highly individualist. Aspect of Interest Collectivist Cultures Individualist Cultures Main Focus Values The person is part of a strong, tight ingroup, such as an extended family, in which people participate from birth. Companies can become tight in-groups, too. Group is more important than the individual – Harmony – Interdependence – Filial piety (deference to elders) – Long-term, cohesive relationships – Groups closely nurture, protect, and guide members, while expecting longterm loyalty from them Loyalty to and emotional dependence on the group, which in turn cares for the wellbeing of the individual Less concern for privacy Achievement – Achievement may be important, but individuals who want attention are restrained (“the nail that stands up must be hammered down”) – Credit or blame for a project is attributed to the group Formality and ritual Fatalism Eloquence and indirectness The person is a separate, unique individual. Individuals are expected to take care of themselves and their immediate families. The unique and special person is more important than the group – Personal rights and needs, such as privacy – Self-reliance, autonomy, and personal responsibility – Individual is to blame for not finding opportunities – High competition, less cooperation – Can-do attitude, anything is possible! Loose relationships – Many interpersonal connections of short duration – Loose, wide networks among people Achievement – Credit or blame for a project is attributed to the individual, rather than the group – Individual task completion and achievement are more important than relationships – Anything can be done with enough effort (not fatalist) – Time is money – Use logic to get things doneSelfreliance, autonomy, and personal responsibility Collectivist Cultures Individualist Cultures High-context communication is largely indirect, with much of the message unsaid and with many meanings and values implicitly shared by others in that culture – but not by outsiders. Most of the meaning is not communicated through the words themselves. Meaning is communicated through facial expression, posture, eye contact, physical contact, tone, status, eloquence (Hall, 1976). Truth emerges nonlinearly, without necessitating consistency or firm logic. Dialectical thinking, or the acceptance of cognitive dissonance (presence of simultaneously incongruous ideas), is more frequent in high-context communicators. High-context communicators think low-context communicators are very rude. Most of the information is in the explicit code, i.e., is openly expressed in words. No need for many contextual cues from tradition, the physical environment, nonverbal behavior, social status, or family background (Hall, 1976). Decisions are largely made on the basis of facts rather than feelings. Discussions are expected to lead to action. Key information is “out on the table,” logically and briefly presented. No patience for eloquence, formalities, circular arguments, dialectical thinking. Yes-no thinking. Legalistic. Low-context communicators distrust highcontext communicators.ng people, unlike the long-term, cohesive relationships found in collectivist cultures. Aspect of Interest Communication Styles The individual is independent, unique, and special Usually Avoiding, Accommodating, perhaps Conflict Styles Compromising Honor (face) is crucial Maintaining face is a key to life Shame is directly tied to face Morality is often related to group shame (or individual shame in reference to the group) Threats to face in collectivist cultures: – Doing anything that harms the group mission or group solidarity – Not following relevant gender-related customs – Using gestures that are offensive – Dressing unacceptably – Losing temper in public – Not using the appropriate greetings (words, Face (honor in the eyes of handshake style, etc.) others; how others see you) – Not learning customs for gifts or hospitality – Constantly rejecting dinner invitations – Not showing gratitude for hospitality – Saying negative things about people – Being overly direct – Making fun of men holding hands in certain collectivist cultures – Asking too many personal questions – Being too demanding, – Stating feelings in a too-direct way – Giving brutally honest feedback that might undermine others’ dignity. Usually Competing, sometimes Collaborating or Compromising Self-face orientation is more prevalent in individualist cultures. Oetzel and TingToomey (2003) found that a concern about maintaining one’s own face was associated positively with the dominating conflict style, which is often attributed to individualist cultures. During a conflict, people from individualist cultures frequently maintain their own face through directness, with the goal of winning (Culpach & Metts, 1994). Cross-cultural relationship management principles: • • • • • Collectivist and individualist cultures need to understand the others’ cultural values. Reach out to the other culture while honoring that culture’s values as much as possible High-context and low-context communicators need to understand each other. Reach out to another culture using that culture’s communication style as much as possible, including during negotiations Across cultures, use cognitive empathy (an interpretation in which you intentionally try to see a situation, action, or person through the eyes of the other culture) Become an informal “cultural anthropologist”: Find a trustworthy cultural informant. Observe cultural dimensions in action. Ask to hear stories and myths. Take notes. Have informal conversations about the culture. Ask yourself “What do I need to understand? Read everything you can! Reframe to avoid stereotypes. Listen well to others. Understand different conflict styles and use the most effective one for the situation; be flexible. Avoid losing face and causing other individuals or cultural groups to lose face (use the appropriate facework strategy).