November 2015 Issue - Northwest Climate Science Center

Northwest Climate Science Digest: Science and Learning Opportunities Combined

November 2015 Issue

The Northwest Climate Science Digest is a monthly newsletter jointly produced by the

Northwest Climate Science Center and the North Pacific Landscape Conservation

Cooperative aimed at helping you stay informed about climate change science and upcoming events and training opportunities relevant to your conservation work. Feel free to share this information within your organization and networks, and please note the role the NW CSC and NPLCC played in providing this service. Do you have a published article or upcoming opportunity that you would like to share? Please send it our way to nwcsc@uw.edu

. Many thanks to those who have provided material for this edition, particularly the Pacific

Northwest Climate Impacts Research Consortium , the Climate Impacts Group and the

Environmental Protection Agency’s Climate Change and Water News . The contents of the

Climate Digest are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NPLCC or the Northwest Climate Science Center.

Subscribe to the NW CSC’s e-mail update list to receive periodic updates on Northwest climate-related information.

Note: In the interest of reducing clutter to your inbox we have combined science content with events and learning opportunities. Please use our hyperlinks to minimize scrolling.

To subscribe or unsubscribe please e-mail nwcsc@uw.edu

.

SCIENCE : Recent climate change-relevant publications, special reports and science resources.

UPCOMING EVENTS : Upcoming climate change-relevant webinars, workshops, conferences, list servers and other learning opportunities.

PREVIOUS ISSUES : An archive of previous Northwest Climate Change Digest issues developed by Region 1 of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Biodiversity/ Species and Ecosystem Response

Saving bull trout from a warming climate

Coastal/Marine Ecosystems/ Ocean Acidification/ Sea Level Rise

Changing El Ninos reduce stability of North American salmon survival rates

Impact of increasing CO2 emissions on the world’s oceans

Aquatic Resources/ Stream Flow/ Hydrology in the Western U.S.

Trends in snow cover and other variables at weather stations in the conterminous US

Patterns of precipitation change and climatological uncertainty

Local variability mediates vulnerability of trout populations to land use and climate change

Improved bias correction techniques for hydrologic simulations of climate change

Projected changes in snowfall extremes and interannual variability of snowfall in the western

Arid Ecosystems

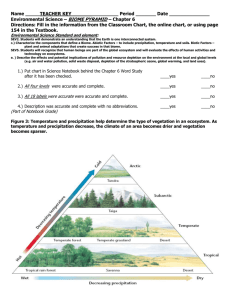

Increased precipitation variability decreases grass productivity and increases shrub productivity

Land Use

Water rights pit growth against rivers

Forests

Larger trees suffer most in drought

Trees can take up to four years to return to normal growth rates after a severe drought

Does climate directly influence Net Primary Productivity globally?

Fire

Tribal and Indigenous Peoples Matters

Tulalip and Swinomish preserve forest and salmon habitat

Climate change could endanger tribal electric systems

Taking Action

Panel to debate long-awaited drought measures

US launches 13 new mini satellites

Carbon Engineering unveils carbon capture project in Squamish, B.C.

Climate and Weather Reports and Services

NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center releases US Winter Outlook

Evaluation of a regional climate modeling effort for the Western United States using a superensemble

Special Reports/ Announcements

Biodiversity/ Species and Ecosystem Response

Earlier spring onset in the western U.S. A new study from the University of Wisconsin examines changes in the onset of spring plant growth. Earlier spring onset may cause phenological mismatches between the availability of plant resources and dependent animals.

This could potentially lead to more false springs, when subsequent freezing temperatures damage new plant growth. The authors of this study used the extended spring indices to project changes in spring onset, and predicted false springs through 2100 in the conterminous United States (US) using downscaled climate projections from the Coupled

Model Intercomparison Project 5 (CMIP5) ensemble. The median shift in spring onset was

23 days earlier in the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 8.5 scenario with particularly large shifts in the Western US and the Great Plains. Spatial variation in phenology was due to the influence of short-term temperature changes around the time of spring onset versus season-long accumulation of warm temperatures. False spring risk increased in the Great Plains and portions of the Midwest, but remained constant or decreased elsewhere. This study concludes that global climate change may have complex and spatially variable effects on spring onset and false springs, making local predictions of change difficult. http://www.nbcnews.com/science/environment/climate-change-means-spring-couldcome-three-weeks-earlier-across-n443856

Allstadt, A. J., Vavrus, S. J., Heglund, P. J., Pidgeon, A. M., Thogmartin, W. E., & Radeloff,

V. C. (2015). Spring plant phenology and false springs in the conterminous US during the

21st century. Environmental Research Letters, 10(10), 104008.

http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/10/10/104008

Saving bull trout from a warming climate: A news story about ecologists attempting a radical new method in conservation biology: physically relocating species that will not survive in their current habitat with a rapidly warming climate. Clint Muhlfeld with the USGS is undertaking one of the largest relocation projects to date, moving bull trout populations to higher elevation lakes in Montana. The project is in its early experimental stages and displays a

“herculean” scientific effort to save the most vulnerable of trout species from a man-made environmental threat. http://www.npr.org/2015/10/08/446354927/scientists-try-radical-move-to-save-bull-troutfrom-a-warming-climate

Coastal/Marine Ecosystems/ Ocean Acidification/ Sea Level Rise

Changing El Ninos reduce stability of North American salmon survival rates: Pacific salmon are a dominant component of the northeast Pacific ecosystem. In this new study, scientists from the Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, UC Davis, and

Georgia Tech address the question of how recent changes in ocean conditions will affect populations of two salmon species (coho and Chinook). Since the 1980s, El Niño Southern

Oscillation (ENSO) events have been more frequently associated with central tropical

Pacific warming (CPW) rather than the canonical eastern Pacific warming ENSO (EPW).

CPW is linked to the North Pacific Gyre Oscillation (NPGO), whereas EPW is linked to the

Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). Here the authors show that both coho and Chinook salmon survival rates along western North America indicate that the NPGO, rather than the

PDO, explains salmon survival since the 1980s. The observed increase in NPGO variance in recent decades was accompanied by an increase in coherence of local survival rates of these two species, increasing salmon variability via the portfolio effect. The portfolio effect is an ecological phenomenon where increased biodiversity leads to increased ecological stability.

Such increases in coherence among salmon stocks are usually attributed to controllable freshwater influences such as hatcheries and habitat degradation, but the unknown mechanism underlying the ocean climate effect identified here is not directly subject to management actions. http://www.pnas.org/content/112/35/10962.short

D. Patrick Kilduff, Emanuele Di Lorenzo, Louis W. Botsford, and Steven L. H. Teo,

Changing central Pacific El Niños reduce stability of North American salmon survival rates, PNAS 2015 112 (35) 10962-10966; published ahead of print August 3,

2015, doi:10.1073/pnas.1503190112

http://pnwcirc.org/study-links-salmon-survival-to-different-climatic-factor/

Abrupt tipping points: One of the most concerning consequences of human-induced increases in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations is the potential for rapid regional transitions in the climate system. Yet, despite much public awareness of how “tipping points” may be crossed, little information is available as to exactly what may be expected in the coming centuries. In this study, a group of scientists assessed all Earth System Models underpinning the recent 5th Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report and

systematically searched for evidence of abrupt changes. The authors found abrupt changes in sea ice, oceanic flows, land ice, and terrestrial ecosystem response, although with little consistency among the models. A particularly large number of abrupt changes was projected for warming levels below 2° C, a warming level commonly acknowledged as safe. The authors discuss mechanisms and include methods to objectively classify abrupt climate change.

Drijfhout, S., Bathiany, S., Beaulieu, C., Brovkin, V., Claussen, M., Huntingford, C., &

Swingedouw, D. (2015). Catalogue of abrupt shifts in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change climate models. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201511451.

http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2015/10/07/1511451112.abstract

Impact of increasing CO

2

emissions on the world’s oceans: Rising anthropogenic CO

2 emissions are anticipated to drive change to ocean ecosystems, but quantitative analyses of this understanding is limited. The authors of this study, Ivan Nagelkerken and Sean D.

Connell, compiled 632 published experiments and quantified the direction and magnitude of ecological change resulting from ocean acidification and warming. They found that primary production by temperate, noncalcifying plankton increased with elevated temperature and

CO

2

, whereas tropical plankton productivity decreased from acidification. In addition, secondary production decreased with acidification in both calcifying and noncalcifying species. In summary, Nagelkerken and Connell showed that ocean acidification and warming increased the potential for an overall simplification of ecosystem structure and function with reduced energy flow among trophic levels and little scope for species to acclimate.

Nagelkerken, I., & Connell, S. D. (2015). Global alteration of ocean ecosystem functioning due to increasing human CO2 emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,

201510856.

http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2015/10/06/1510856112.abstract

Aquatic Resource/ Stream Flow/ Hydrology in the Western U.S.

Trends in snow cover and other variables at weather stations in the conterminous

US: Noah Knowles from the USGS used three statistical analyses (trend tests, linear regression, and canonical correlation analysis) to study National Weather Service

Cooperative Observer (COOP) changes to snow depth data from 1950-2010. Knowles showed that patterns toward later snow-cover onset in the western half of the conterminous

United States and earlier snow-cover onset in the eastern half, combined with a widespread trend toward earlier final meltoff of snow cover produced shorter snow seasons in the eastern half of the United States and longer snow seasons in the Great Plains and southern

Rockies. Additionally, the annual total number of days with snow cover exhibited a widespread decline. Knowles concluded that temperature is the dominant variable influencing snow cover during the warmer snow-season months, while the colder months are dominated by a combination of temperature and precipitation. A canonical correlation analysis indicated that most trends presented here took hold in the 1970s, consistent with the temporal pattern of global warming during the study period.

Knowles, N. (2015). Trends in Snow Cover and Related Quantities at Weather Stations in the Conterminous United States. Journal of Climate, 28(19), 7518-7528.

http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/JCLI-D-15-0051.1

Patterns of precipitation change and climatological uncertainty: Projections of changes in precipitation from global warming scenarios display disagreement at regional scales.

Scientists from UCLA, the State University of New Jersey, and Boston University examined spatial patterns of disagreement in the simulated climatology and end-of-century precipitation changes in phase 5 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5) archive. The term principal uncertainty pattern (PUP) was used for any robust mode calculated when applying these techniques to a multimodel ensemble. This study found two

PUPs in the tropics, one at the margins of the convection zones and the other in the Pacific cold tongue. Both modes appear to arise primarily from differences in the response to radiative forcing, distinct from internal variability. The leading storm-track PUPs for precipitation and zonal wind change exhibited similarities to the leading uncertainty patterns for the historical climatology, which indicated important and parallel sensitivities in the eastern Pacific storm-track. However, expansion coefficients for climatological uncertainties tended to be weakly correlated with those for end-of-century change.

Langenbrunner, B., Neelin, J. D., Lintner, B. R., & Anderson, B. T. (2015). Patterns of precipitation change and climatological uncertainty among CMIP5 models, with a focus on the midlatitude Pacific storm track. Journal of Climate, (2015).

http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00800.1

Local variability mediates vulnerability of trout populations to land use and climate change: Land use and climate change occur simultaneously around the globe. Fully understanding their separate and combined effects requires a mechanistic understanding at the local scale where their effects are ultimately realized. In this study, a group of researchers applied an individual-based model of fish population dynamics to evaluate the role of local stream variability in modifying responses of Coastal Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii

clarkii) to scenarios simulating identical changes in temperature and stream flows linked to forest harvest, climate change, and their combined effects over six decades. The study found that climate change most strongly influenced trout (earlier fry emergence, reductions in biomass of older trout, increased biomass of young-of-year), but these changes did not consistently translate into reductions in biomass over time. Forest harvest, in contrast, produced fewer and less consistent responses in trout. Earlier fry emergence driven by climate change was the most consistent simulated response, whereas survival, growth, and biomass were inconsistent. Overall the findings from this study indicate that a host of local processes can strongly influence how populations respond to broad scale effects of land use and climate change.

Penaluna, B. E., Dunham, J. B., Railsback, S. F., Arismendi, I., Johnson, S. L., Bilby, R. E., ...

& Skaugset, A. E. (2015). Local variability mediates vulnerability of trout populations to land use and climate change. PloS one, 10(8), e0135334.

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0135334

Improved bias correction techniques for hydrologic simulations of climate change:

Global climate model output typically needs to be bias corrected before it can be used for climate change impact studies. Researchers from Scripps, USGS, Santa Clara and University of Idaho applied three existing bias correction methods, and one new one they developed, to daily maximum temperature and precipitation from 21 global climate models (GCMs) to investigate how different methods alter the climate change signal of the GCM. The quantile mapping (QM) and cumulative distribution function transform (CDF-t) bias correction methods significantly altered the GCM’s mean climate change signal, with differences of up to 2°C and 30 percentage points for monthly mean temperature and precipitation, respectively. Equidistant quantile matching (EDCDFm) bias correction preserved GCM changes in mean daily maximum temperature, but not precipitation. An extension to

EDCDFm termed PresRat was introduced, which generally preserved the GCM changes in mean precipitation. Another problem is that GCMs can have difficulty simulating variance as a function of frequency. To address this, a frequency-dependent bias correction method was introduced that is twice as effective as standard bias correction in reducing errors in the models’ simulation of variance as a function of frequency, and does so without making any locations worse, unlike standard bias correction. Lastly, a preconditioning technique was introduced that improved the simulation of the annual cycle while still allowing the bias correction to take account of an entire season’s values at once.

Pierce, D. W., Cayan, D. R., Maurer, E. P., Abatzoglou, J. T., & Hegewisch, K. C. (2015).

Improved bias correction techniques for hydrological simulations of climate change. Journal

of Hydrometeorology, (2015).

http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/abs/10.1175/JHM-D-14-0236.1

Projected changes in snowfall extremes and interannual variability of snowfall in the

western United States: Projected warming will have significant impacts on snowfall accumulation and melt, with implications for water availability and management in snowdominated regions. Changes in snowfall extremes are confounded by projected increases in precipitation extremes. Three scientists from the University of Idaho bias-corrected downscaled climate projections from 20 global climate models to montane Snowpack

Telemetry stations across the western United States. The study assessed mid-21st century changes in the mean and the variability of annual snowfall water equivalent (SFE) and extreme snowfall events. The researchers found that changes in the magnitude of snowfall event quantiles were sensitive to historical winter temperature. At climatologically cooler locations, such as in the Rocky Mountains, changes in the magnitude of snowfall events mirrored changes in the distribution of precipitation events, with increases in extremes and less change in more moderate events. By contrast, declines in snowfall event magnitudes were found for all quantiles in warmer locations. Common to both warmer and colder sites was a relative increase in the magnitude of snowfall extremes compared to annual SFE and a larger fraction of annual SFE from snowfall extremes. The coefficient of variation of annual

SFE increased up to 80% in warmer montane regions due to projected declines in snowfall days and the increased contribution of snowfall extremes to annual SFE. In addition to declines in mean annual SFE, more frequent low-snowfall years and less frequent highsnowfall years were projected for every station.

Lute, A. C., J. T. Abatzoglou, and K. C. Hegewisch (2015), Projected changes in snowfall extremes and interannual variability of snowfall in the western United States, Water Resour.

Res., 51, 960–972, doi: 10.1002/2014WR016267 .

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2014WR016267/full

Arid Ecosystems

Increased precipitation variability decreases grass productivity and increases shrub productivity: The impacts of projected variation in precipitation on functional diversity have received limited attention. Two scientists from Arizona State University examined the impact of increased levels of precipitation on the functional diversity of grass populations using a 6-year rainfall manipulation experiment. Five precipitation treatments were switched annually, resulting in increased levels of precipitation variability while maintaining average precipitation constant. Functional diversity showed a positive response to increased variability due to increased evenness. Dominant grasses decreased and rare plant functional types increased in abundance because grasses showed a hump-shaped response to precipitation with a maximum around modal precipitation, whereas rare species peaked at high precipitation values. Increased functional diversity ameliorated negative effects of precipitation variability on primary production. Rare species buffered the effect of precipitation variability on the variability in total productivity because their variance decreases with increasing precipitation variance.

Gherardi, L. A., & Sala, O. E. (2015). Enhanced interannual precipitation variability increases plant functional diversity that in turn ameliorates negative impact on productivity. Ecology

letters.

http://www.researchgate.net/publication/282645030_Enhanced_interannual_precipitation_ variability_increases_plant_functional_diversity_that_in_turn_ameliorates_negative_impact_ on_productivity

Land Use

Water rights pit growth against rivers: Washington may be entering a new era of water rights management, according to this news story from a small town, Yelm, with emerging water rights issues. Yelm is a junior water rights holder whose current method of obtaining enough water from the state is being outgrown by its population. New plans to keep up with

Yelm’s population may have negative environmental consequences, particularly on the nearby Nisqually River. http://www.king5.com/story/tech/science/environment/2015/10/12/yelm-water-rightsfarmer/73846116/?utm_source=E-clips&utm_campaign=7aedd6af0d-

E_clips_October_19_201510_19_2015&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_c909fc207a-

7aedd6af0d-388501765

Forests

Larger trees suffer most in drought: The frequency of severe droughts is increasing in many regions around the world as a result of climate change. Droughts alter the structure and function of forests. Site- and region-specific studies suggest that large trees, which play keystone roles in forests and can be disproportionately important to ecosystem carbon storage and hydrology, exhibit greater sensitivity to drought than small trees. In this new study, a group of researchers synthesized data on tree growth and mortality collected during

40 drought events in forests worldwide to see whether this size-dependent sensitivity to drought applies more widely. The authors found that droughts consistently had a more detrimental impact on the growth and mortality rates of larger trees. Moreover, droughtrelated mortality increased with tree size in 65% of the droughts examined, especially when community-wide mortality was high or when bark beetles were present. The more pronounced drought sensitivity of larger trees could be underpinned by greater inherent vulnerability to hydraulic stress, the higher radiation and evaporative demand experienced by exposed crowns, and the tendency for bark beetles to preferentially attack larger trees. The authors of this study suggest that future droughts will have a more detrimental impact on the growth and mortality of larger trees, potentially exacerbating feedbacks to climate change.

Bennett, A.C., McDowell, N.G., Allen, C.D., & Anderson-Teixeria, K.J. (2015). Larger trees suffer most during drought in forests worldwide. Nature Plants 1, Article number: 15139. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.139

http://www.nature.com/articles/nplants2015139

Trees can take up to four years to return to normal growth rates after a severe

drought: The impacts of climate extremes on terrestrial ecosystems are poorly understood but important for predicting carbon cycle feedbacks to climate change. Coupled climate– carbon cycle models typically assume that vegetation recovery from extreme drought is immediate and complete, which conflicts with the understanding of basic plant physiology.

In this new study, a team of scientists examined the recovery of stem growth in trees after severe drought at 1,338 forest sites across the globe, comprising 49,339 site-years, and compared the results with simulated recovery in climate-vegetation models. The team found pervasive and substantial “legacy effects” of reduced growth and incomplete recovery for 1 to 4 years after severe drought. Legacy effects were most prevalent in dry ecosystems, among

Pinaceae, and among species with low hydraulic safety margins. In contrast, limited or no legacy effects after drought were simulated by current climate-vegetation models. The results of this study highlight hysteresis in ecosystem-level carbon cycling and delayed recovery from climate extremes.

Anderegg, W. R. L., Schwalm, C., Biondi, F., Camarero, J. J., Koch, G., Litvak, M., & Pacala,

S. (2015). Pervasive drought legacies in forest ecosystems and their implications for carbon cycle models. Science, 349(6247), 528-532.

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/349/6247/528

Does climate directly influence Net Primary Productivity globally?: A new article published by Global Change Biology refutes the findings of a 2014 study (Michaletz et al. 2014) that concluded that climate change has little to no influence on Net Primary Productivity

(NPP). The authors of this paper re-analyzed the same database that was used in the 2014

study to partition the direct and indirect effects of climate on NPP, using three approaches: maximum-likelihood model selection, independent-effects analysis, and structural equation modeling. These new analyses showed that about half of the global variation in NPP could be explained by total stand biomass (Mtot) combined with climate variables and supported strong and direct influences of climate independently of Mtot, both for NPP and for net biomass change averaged across the known lifetime of the stands (ABC = average biomass change). The authors showed that the length of a growing season is an important climate variable, intrinsically correlated with, and contributing to mean annual temperature and precipitation (Tann and Pann). The analyses in this paper provide guidance for statistical and mechanistic analyses of climate drivers of ecosystem processes for predictive modeling and provide novel evidence supporting the strong, direct role of climate in determining vegetation productivity at the global scale.

Chu, C., Bartlett, M., Wang, Y., He, F., Weiner, J., Chave, J., & Sack, L. (2015). Does climate directly influence NPP globally?. Global change biology.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.13079/abstract

Fire

Vegetation, topography and daily weather influenced burn severity in central Idaho

and western Montana forests: Burn severity is useful for evaluating fire impacts on ecosystems. Scientists infer burn severity using the satellite-derived differenced Normalized

Burn Ratio (dNBR). While this is a useful tool, the environmental controls on burn severity across large forest fires are both poorly understood and likely to be different than those influencing fire extent. In this study, scientists from University of Idaho and the USDA in

Montana related dNBR to environmental variables including vegetation, topography, fire danger indices, and daily weather for daily areas burned on 42 large forest fires in central

Idaho and western Montana. The 353 fire days that were analyzed burned 111,200 ha as part of large fires in 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2011. The researchers found that percent existing vegetation cover had the largest influence on burn severity, while weather variables like fine fuel moisture, relative humidity, and wind speed were also influential but somewhat less important. The authors posit that, in contrast to the strong influence of climate and weather on fire extent, ‘‘bottom-up’’ factors such as topography and vegetation have the most influence on burn severity. While climate and weather certainly interact with the landscape to affect burn severity, pre-fire vegetation conditions due to prior disturbance and management strongly affect vegetation response even when large areas burn quickly.

Birch, D. S., Morgan, P., Kolden, C. A., Abatzoglou, J. T., Dillon, G. K., Hudak, A. T., &

Smith, A. M. (2015). Vegetation, topography and daily weather influenced burn severity in central Idaho and western Montana forests. Ecosphere, 6(1), art17.

http://www.esajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1890/ES14-00213.1

Tribal and Indigenous Peoples Matters

Tulalip and Swinomish preserve forest and salmon habitat: Two significant environmental initiatives were implemented in the last month. The first was on August 28 at

Tulalip, when bulldozers removed about 1,500 linear feet of levee in the Snohomish River’s

Qwuloolt Estuary, reopening 350 acres of wetlands to threatened salmon and other species.

It’s part of what is reportedly the largest restoration project so far in the Snohomish River watershed. The second initiative was implemented thirty-two miles north, on the Swinomish

Reservation, where the Swinomish Tribe and Ecotrust will use a $528,000 three-year grant to develop a forest conservation plan. The plan is being developed with public input and could include carbon sequestration credits, conservation easements and forestland acquisition. http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/09/24/tulalip-swinomish-preserveforest-and-salmon-habitat-two-significant-initiatives-161863

Climate change could endanger tribal electric systems: A new report from the U.S.

Department of Energy has suggested that heat waves, extreme storms, wildfire and other effects of climate change pose major threats to the electric power systems in Native

American communities across the country, most significantly in the West and Southwest.

The DOE produced the report to help tribes, especially those such as the Navajo Nation that own and manage many of their power lines, understand the vulnerabilities of their power systems so they can adapt to the risks posed by a warming world. According to the report, tribes across the country are likely to pay more for their electricity as high heat forces residents to use air conditioners more often, increasing demand for electricity. Severe storms and heatwaves are likely to damage power lines more frequently and disrupt the supply of fuel to power plants, causing more frequent power outages. And, extreme heat is likely to reduce the power generation capacity at some power plants because of their inability to keep cool during heatwaves.

http://www.climatecentral.org/news/climate-change-tribes-electric-power-risk-19415

To download report: http://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2015/09/f26/Tribal%20Energy%20Vulnerabilities%20t o%20Climate%20Change%208-26-15b.pdf

Federal appeals judges hear challenges to fish-passage ruling: The most recent development in a long history of litigation between Washington State and Native American tribes: a federal appeals judge will weigh whether Washington State should have to spend billions of dollars to replace culverts that block migrating salmon. The argument is based on mid-19 th Century treaties that say tribes don't just have a right to fish but for there to be fish to catch. When culverts are designed in such a way that block salmon from spawning, there are no fish to catch, consequently violating tribal rights. Washington State has said it would need to fix 30 to 40 culverts each year until 2030, spending $155 million annually, to comply, making this a complex and expensive issue. http://www.theolympian.com/news/state/washington/article39385668.html?utm_source=

E-clips&utm_campaign=7aedd6af0d-

E_clips_October_19_201510_19_2015&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_c909fc207a-

7aedd6af0d-388501765

US launches 13 new mini satellites: Thirteen miniature CubeSats, satellites made up of one or more cube-like modules roughly the size of coffee mugs, were launched alongside a

classified U.S. spy satellite deployment. Among the 13 new CubeSats was one developed from a Native American college. The satellite, named BisonSat, is the first CubeSat from a

Native American college to go to space. BisonSat includes space-based imagery capabilities that will be useful for tribal governments making land use decisions. https://eos.org/articles/u-s-launches-13-new-minisatellites

Taking Action

Panel to debate long-awaited drought measures: Efforts to pass Western drought legislation are about to be made public as Sen. Lisa Murkowski's (R-Alaska) Energy and

Natural Resources Committee holds a long-awaited legislative hearing on the two lead

California-specific relief measures. Bills dealing with more preventative drought measures in many other western states are also emerging alongside the two immediate California relief measures. One of prominence is from Washington State Sen. Maria Cantwell. Her legislation

(S.1694) authorizes a water-sharing agreement in Washington state’s agriculture-heavy and drought-hit Yakima River Basin. Legislation from other states will likely enter the discussion as well. http://www.eenews.net/stories/1060025813

Carbon Engineering unveils carbon capture project in Squamish, B.C.: A carbon capturing company called Carbon Engineering, founded by Harvard scientist David Keith and funded by big investors (including Bill Gates), has unveiled their pilot plant in Squamish,

B.C. The plant moves large volumes of air through an instrument that absorbs CO

2

via a liquid solution and then transforms it into pellets of calcium carbonate. The pellets are then heated to 800 or 900 degrees Celsius and break down, releasing pure carbon. The company plans to further build upon this operation with technology that will turn this pure carbon into renewable fuel. Many groups are already interested in this future product, and the company hopes to scale up their operations to eventually capturing up to one million tonnes of CO

2

per day.

http://www.cbc.ca/m/news/canada/british-columbia/topstories/carbon-capturesquamish-1.3263855

Climate and Weather Reports and Services

NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center releases US Winter Outlook: Forecasters at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center issued the U.S. Winter Outlook today favoring cooler and wetter weather in Southern Tier states with above-average temperatures most likely in the West and across the Northern Tier. This year’s El Niño, among the strongest on record, is expected to influence weather and climate patterns this winter by impacting the position of the Pacific jet stream. http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2015/101515-noaa-strong-el-nino-sets-the-stage-for-

2015-2016-winter-weather.html

NOAA’s Winter Outlook found here:

http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/long_range/fxus05.html

Evaluation of a regional climate modeling effort for the Western United States using

a superensemble: A group of scientists from OSU, the Union of Concerned Scientists, and

Oxford compared simulations from a regional climate model (RCM) as part of a superensemble experiment with observational data over the western United States. Overall, the means of seasonal temperature were well represented in the simulations. Additionally, the overall magnitude and spatial pattern of precipitation were well characterized, though somewhat exaggerated along the coastal mountains, Cascade Range, and Sierra Nevada. The simulations also produced regional U.S. weather patterns associated with El Niño. The superensemble simulated the observed spatial pattern of mean annual temperature more faithfully than any of the RCM–GCM pairings in the North American Regional Climate

Change Assessment Program (NARCCAP), and its errors in mean annual precipitation fell within the range of errors of the NARCCAP models. Lastly, this paper provided examples of the size of an ensemble required to detect changes at the local level and demonstrated the effect of parameter perturbation on regional precipitation.

Sihan Li, Philip W. Mote, David E. Rupp, Dean Vickers, Roberto Mera, and Myles Allen.

(2015). Evaluation of a Regional Climate Modeling Effort for the Western United States Using a

Superensemble from Weather@home . Journal of Climate, Vol. 28, No. 19 : pp. 7470-7488

(doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00808.1) http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00808.1

Special Reports/Announcements

Department of Energy’s Office of Indian Energy soliciting applications from Indian

tribes for clean energy projects: The Funding Opportunity Announcement is soliciting applications under two Topic Areas. Topic Area 1: Install clean energy and energy efficiency retrofit projects for tribal buildings, Topic Area 1.a.: Clean Energy Systems, Topic Area 1.b.:

Deep Energy Retrofit Energy Efficiency Measures. Topic Area 2: Deploy clean energy systems on a community scale. https://eere-exchange.energy.gov/Default.aspx#FoaId4a7967f3-f608-497f-a02d-

95c215342d15

OLYMPEX announcement: In a few weeks a veritable army of meteorologists will descend upon the Olympic Mountains of Washington State with radars, aircraft, rain gauges, and other meteorological sensors. All of these resources and participants will be part of the OLYMPEX field program, whose primary goal will be to help NASA evaluate and improve its latest earth-observation satellite: the GPM satellite, which possesses an advanced downward-looking weather radar. But OLYMPEX will be much more, with a huge suite of observing systems that will probably produce the most comprehensive description of clouds and precipitation over any mountain barrier on the planet. http://cliffmass.blogspot.com/2015/10/olympex-starts-next-month.html

UPCOMING EVENTS

11/2-11/3 - Conference, Sacramento, CA. 2015 Southwest Climate Summit

11/3-11/5 – Conference, Cambridge, MA. 2015 Rising Seas Summit

11/4 – Training, Sacramento, CA. Climate Smart Conservation Training

11/4-11/5 – Conference, Coeur d'Alene, ID. Sixth Annual Pacific Northwest Climate Science

Conference

11/8-11/12 – Conference, Portland, OR.

CERF 23 rd Biennial Conference

11/9 – Online Course, Climate Change Policy and Public Health

11/10 – 10am – Webinar. BIA’s Climate Change Competitive Award Process Overview

11/12, 10am – Webinar. OneNOAA Science Seminar: Ocean Parks & The National Park

Service Centennial

11/12-11/13 – Workshop, Cody, WY. First workshop of WGA Species Conservation and

ESA Initiative

11/12-11/3 – Conference, Cambridge, MA. Rising Seas Summit

11/16-11/19 – Conference, Denver, CO. 2015 AWRA Annual Water Resources Conference

11/20 – Deadline. Applications for USDA Climate Hubs Fellows Program

12/1 – Deadline. Abstracts Due: NOAA’s Climate Prediction Applications Science

Workshop

List Servers

BioClimate News & Events from NCCWSC & the CSCs

ClimateNews-- is a snapshot from British Columbia’s Ministry of Forests, Lands and

Natural Resource Operations, provides new and emerging climate change adaptation and mitigation activities in the natural resource sector. Contact: katharine.mccallion@gov.bc.ca

Climate CIRCulator (Oregon Climate Change Research Institute)

Climate Impacts Group (Univ. Washington)

Earth to Sky Newsletter (NASA/DOI Partnership): anita.l.davis@nasa.gov

EPA Climate Change and Water E-Newsletter

FRESC monthly e-newsletter: Contact fresc_outreach@usgs.gov

FWS CC Monthly E-Newsletter: Contact kate_freund@fws.gov

LCC list servers (see your LCC’s website ) and the national LCC Network newsletter

Ocean Acidification Report

OneNOAA Science Webinars

NASA's Climate Change Newsletter climate-feedback@jpl.nasa.gov

North Pacific LCC Listserve – North Pacific Tidings - important news and announcements; and NPLCC Climate Science Digest - new science/information affecting natural and cultural resources.

NCTC Climate Change List server (upcoming webinars and courses): contact christy_coghlan@fws.gov

Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions (PICS) (British Columbia) Climate News Scan- a weekly summary of the major climate-change related science, technology, and policy advances of direct relevance to the BC provincial and the Canadian federal governments and more generally to businesses and civil society

PointBlue Weekly Ecology, Climate Change and Related e-Newsletter: Contact ecohen@prbo.org

PNW Tribal Climate Change Network : Contact kathy@uoregon.edu

US Forest Service Fish & Wildlife Research Updates

USGS Climate Matters

White House Energy and Environment Updates