Chapter-3-Current-state-of-biodiversity

advertisement

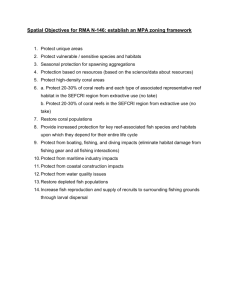

Dutch Caribbean Biodiversity Strategy (draft version 10.2) 23rd December 2013 Chapter 3 Current State of Biodiversity All nature conservation organisations and/or government bodies are requested to submit the updated information for their island to the DCNA Secretariat before the end of February 2014. !! Please highlight all changes with Track Changes !! In case you make any other changes outside the scope of this section of the document, please contact research@dcnanature.org to make sure your changes don’t get lost. Biodiversity Strategy for the Dutch Caribbean 3. Current state of biodiversity Biological diversity – biodiversity – is the variety of life and its processes and it includes the variety of living organisms, the genetic differences amongst them and the communities and ecosystems in which they occur. This section presents a summary of our current knowledge of the state of the islands’ biological resources. Since biodiversity in the Dutch Caribbean has not been systematically inventoried and indicators for species and/or ecosystem trends have not been identified information is incomplete. In general, expert qualitative assessments reveal that all natural habitats show minor or severe signs of degradation. Considering the fact that many endemic and other species depend on the small island habitats it’s obvious that the current status of biodiversity on the islands is threatened [ref: xxx] Habitats The main marine habitats found on and around the islands are coral reefs, mangroves, seagrasses, macro-algal communities, open ocean and a range of subtidal and intertidal habitats including hard, rubble and sand bottoms, rocky shores, sand/rubble beaches, salt and freshwater ponds as well as saliñas and lagoons. The main terrestrial habitats are semi-desert, dry scrub, dry forest, other woodlands and rainforest and cloudforest. All of these environments are biologically diverse and provide a range of resources and ‘services’ for wild animals and plants as well as humans. Coral reefs, mangrove forests, seagrass beds and rainforests and cloudforests are all recognised as globally threatened ecosystems of high biodiversity. A number of threats are contributing to declines in health and extent of these habitats as well as others in the Dutch Caribbean. Coral reefs Coral reefs occur around all islands of the Dutch Caribbean and are diverse in structure and extent. Bonaire and Curaçao have highly developed fringing coral reefs, which encircle the entire islands. St Maarten has patch/barrier reefs while the reefs on Saba are found on the top of underwater seamounts or pinnacles. St Eustatius by contrast has well developed patch reefs and Aruba has small areas of patch reef amongst a topographically complex marine landscape. Coral cover has systematically declined throughout the Caribbean by more than 80% since the 1970s due to a number of factors including chronic overfishing, the insidious effects of population expansion and coastal zone development, climate -2- Biodiversity Strategy for the Dutch Caribbean change – which is causing more intense and more frequent storms as well as frequent coral bleaching events and acidification - and invasive species. Many of the large reef fish (particularly groupers, snappers and grunts) are declining at the same or even greater rate than corals. The greatest threat to fish populations is posed by invasive lionfish, which were first spotted on the ABC islands late 2009 and by 2011 were also established on the SSS islands. The situation looks grim as lionfish appear to colonize all depths and habitats and this voracious predator is capable of reducing in situ juvenile fish populations by up to 78%. Aruba’s patches of coral reefs are widely dispersed and discrete. Little is known about their status and they are not protected. Bonaire’s fringing coral reefs, which extend around the island of Bonaire and satellite island of Klein Bonaire are protected within the Bonaire National Marine Park and include the Ramsar areas of Lac (Ramsar site # 199) and the fringing reefs around Klein Bonaire (Ramsar site # 201). Within the Marine Park are two Marine Reserves, where all activities are prohibited and two small Fish Protected Areas where fishing activities are banned. Bonaire’s coral reefs are considered to be some of the healthiest in the Caribbean (AGRRA, Carmabi Foundation, 2011), yet remain seriously threatened with collapse, more so than at any time since monitoring began (Steneck et al. 2011). Populations of grouper, snapper and grunt have plummeted since data was first collected in the early 1970s. Curacao’s fringing coral reefs extend around the island. They are not actively managed although the Curacao Underwater Park officially protects xx of coastline. The coral reefs, particularly in the area adjacent to Oostpunt, are generally regarded as among the healthiest in the Caribbean (Carmabi Foundation, 2011). Saba’s pinnacles xxx [extent – management – status] The patch reefs on St Eustatius xxx [extent – management – status] St Maarten recently established the Man o War Shoals Marine Park to protect their most valuable areas of coral reefs. [extent – management – status] Mangrove forests It is well known that there is considerable interchange between mangrove forest ecosystems and coral reefs with mangroves and adjoining seagrass beds acting as breeding and nursery grounds for countless species of fish and invertebrates many of which spend their adult lives in coral reef environments. Mangroves are also considered globally threatened ecosystems and are under significant pressure throughout the Caribbean region. -3- Biodiversity Strategy for the Dutch Caribbean In the Dutch Caribbean mangrove forests are found on Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao and St. Maarten, consisting of Red Mangrove (Rhizophora mangle), Black Mangrove (Avicennia germinans), White Mangrove (Laguncularia racemosa)and Buttonwood (Conocarpus erectus). Despite the active management offered by protected areas and Ramsar site designation, mangroves are still being cleared for coastal development. This is a particular problem on St Maarten and Curaçao. On Aruba, well-developed mangrove forests occur at Spanish Lagoon (Spaans Lagoen). This is a Ramsar site (# 198), but falls outside of the Parke Nacional Arikok and is therefore not under active management. The status of the mangrove forests is not known. Bonaire’s best developed mangrove forests are found encircling Lac, a large semienclosed bay on the windward shore although mangrove stands are also found at Lagoen and red mangroves have been slowly but systematically colonizing the southern coastal fringe on the leeward shore of Bonaire for over a decade. The mangroves at Lac are well protected within the Bonaire National Marine Park and are a Ramsar site. Special attention has been paid to the study and management of Lac for over twenty years. The mangrove forest is made up of approximately equal parts Red Mangrove, on the seaward edge and Black Mangrove, which colonize the drier interior areas. Changed hydrology and/or natural progression has caused the mangroves in the north-western corner of the bay (at Awa di Lodo) to die off decades ago though the area is now being slowly recolonized by Black Mangrove. Despite this, and increasing tourist use of the bay, the mangrove forests at Lac are considered to be in very good condition and recent studies have shown a high rate of land reclamation (a natural process of mangroves growing seaward and dying off further in land) at Lac Bay Bonaire (Engel, 2013). The unusual hydrology of the bay, with two independent basins, sand bars and fresh water replenishment via sheet flow, puts the mangroves on the landward fringe at risk and the invertebrate life in the mangrove forests appears depleted. On Curacao mangrove forests can be found xxx [extent – management – status] An incident of oil pollution at Jan Kok on 2012 resulted in xxx Few of the mangrove forests on St Maarten have escaped land clearance for development. There are still mangroves at xxx [extent – management – status] Little systematic monitoring has been done of mangrove forests in the Dutch Caribbean. Analysis of satellite images may be the most suitable method for monitoring areal extent, species composition, and health of mangrove areas in the Dutch Caribbean (IMARES, 2012). -4- Biodiversity Strategy for the Dutch Caribbean Seagrass Seagrass ecosystems often occur alongside coral reefs and play a vital role in maintaining the health and diversity of adjacent coral reefs. They also form important habitat for the globally endangered Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) and locally threatened Queen Conch (Lobatus gigas). Seagrass beds are sensitive to landbased pollution, sedimentation, trampling and invasive species, and climate change. Aruba has extensive sea grass beds around the island. These are not protected and have not been well studied. The seagrass beds at Lac on Bonaire have been studied since 1969 (Wagenaar Hummelinck and Roos). There has been some decline in the extent and coverage of native seagrass [extent – management – status] On Curacao, seagrass beds can be found [extent – management – status] Extensive seagrass beds are found around St Eustatius xxx [extent – management – status] St. Maarten has extensive seagrass beds in the Simpson Bay lagoon and xxx. None of St Maarten’s seagrass beds are protected or under active conservation management. Much of the Simpson Bay lagoon has been overrun by the invasive H.stipulacea. An invasive seagrass (Halophila stipulacea) has been found on St. Maarten, Curaçao and Bonaire. The average coverage of H.stipulacea in Lac has increased 14%, in three years (Engel, 2013). Rainforest Tropical rainforests are among the most threatened ecosystems globally due primarily to logging and agricultural clearance. Globally, rainforests now cover less than 6% of Earth’s land surface. The rainforests occur on Saba and St. Eustatius Saba’s rain forests cover the steep slopes of the island from an altitude of xx to the top of Mount Scenery. Most are protected by the Saba Conservation Foundation and some fall within the islands terrestrial protected area. [extent – management – status] Statia’s rain forests are found around the top of the Quill crater within the Quill Boven National Park [extent – management – status] however they remain at threat to invasive species, climate change and hurricanes. Species The Dutch Caribbean is home to the greatest level of biodiversity within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. There are over 200 endemic plants and animals in the ABC Islands alone that cannot be found anywhere else in the world. -5- Biodiversity Strategy for the Dutch Caribbean 75 globally endangered or vulnerable species are present on the islands, including trees, snakes, sea turtles, birds, whales and fish. These species are facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the medium to near future and many are protected by local and international law (see Appendix I for specially protected species in the Dutch Caribbean). Birds Birds often provide an indication of changing environmental conditions. In addition to the designation of 23 Important Bird Areas, local conservation organizations and BirdLife International have identified 26 locally or globally important or threatened bird species. Audubon’s Shearwater (Puffinus lherminieri) The Audubon’s Shearwater is listed as IUCN category Least Concern. Global population estimated at (minimum) to be 500,000 individuals (Croxall et al. 2012). Population trend thought to be declining throughout the region, with dramatic declines at some location, but few specific data. Distribution is poorly known due, in part, to their nocturnal behaviour and activity patterns, and the remoteness and steepness of their nesting terrain. The Audubon’s Shearwater has a population estimate for the Lesser Antilles thought to be approximately 3,000 pairs (Bradley and Norton, 2009). These estimates are largely based on aerial or calling birds and thus subject to inaccuracy and multiple counting. Caribbean Coot (Fulica caribaea) The species is listed as Near Threatened by IUCN. The total Caribbean population is estimated at 40,000 individuals (BirdLife International 2008). There are no data available on population trends, productivity, nesting requirements, and specific habitat use. The Caribbean Coot population was estimated at 250 individuals on Bonaire (Well et al., 2008), 280 individuals on Aruba (Delnevo 2008), 1,000 individuals on Curaçao (Debrot et al. 2008), and 75 individuals on St. Maarten (Collier and Brown 2008). Note that these population numbers refer to the respective Important Bird Areas (IBA) for each island. Periodic wetland areas do occur following seasonal rains, particularly on Aruba, and provide ephemeral habitat for this species. Consequently, population estimates may be higher than noted here. There are no breeding records for this species on Saba or St. Eustatius. Common terns (Sterna hirundo) Common terns do not breed in the Dutch Lesser Antilles. This species nests on Aruba (165 individuals; Delnevo 2008), Bonaire (115 individuals; Wells et al., 2008), and Curaçao (400 individuals; Debrot et al., 2008). These three islands represent the most significant population for this species in the Caribbean. However, some caution should be expressed as the very similar (tropical form) roseate tern is often confused with common tern. Least terns (Sternula antillarum) -6- Biodiversity Strategy for the Dutch Caribbean Least terns occur primarily on Bonaire where an estimated 2,375 individuals have been reported (Wells et al. 2008). On Curaçao 1,860 individuals have been recorded (Wells et al., 2008). A long-term study of terns on Aruba has identified a population of ca. 480 individuals. On St. Maarten the national population is estimated at 450 individuals (Collier and Brown 2008), although recent estimates (2009 and 2010) only list 10 individuals (EPIC 2012). There are no records on breeding least terns on Saba or St. Eustatius. The only population trend exists for Aruba where all nesting tern species have been studied intensively since 1999. Least terns nesting pairs on Aruba have fluctuated widely at some colonies and have ranged from 0 to 55 pairs. The smaller (5-15 pair) colonies tend to remain more stable, and the large fluctuations at the bigger colonies reflect movements between areas. Marked interyear and inter-colony movement (based on individually marked birds) demonstrates movement but an overall population stability. However, productivity tends to be lower for those colonies exhibiting inter-year movement Delnevo pers. comm.) Northern Caracara (Caracara cheriway) The Northern Caracara is rare and localized in the Lesser Antilles. This species does not breed on St. Maarten, Saba and St. Eustatius. It does breeds on Aruba, Curaao, and Bonaire. Population data exists for Aruba, but we are not aware of any population status or trend data for either Bonaire or Curaçao. In 2006, Delnevo (pers.comm.) used 52 standardized point counts (based on stratified random design), to estimate a total of 28 nesting pairs and 60 individual Caracara on Aruba. Since 2006, the prevalence of northern Caracara within standardised counts has declined to an estimated 52 total individuals in 2011. Comparable data are not available for other islands. Yellow-shouldered Amazon (Amazona barbadensis) Bonaire’s Yellow-shouldered Amazon parrot is listed as Vulnerable on IUCN’s Redlist. Habitat loss, degradation and human conflict and poaching are threatening the sustainability of Bonaire’s population. Red-billed Tropicbirds Sea Turtles Global trends of sea turtle populations continue to trend downward, bringing the several species close to the brink of extinction. Of the seven species of sea turtles, four are regulars in the Dutch Caribbean. The Green, Loggerhead, Hawksbill and Leatherback sea turtles have been documented to nest on our islands with Saba being the only island not known as a successful turtlenesting area due to the lack of sandy beaches. The rare and outstanding presence of the Olive Ridley in the Dutch Caribbean is generally attributed to a lost-in-migration individual. Lesser Antillean Iguana (Iguana delicatissima) The Lesser Antillean Iguana only remains on St. Eustatius. Population sizes on St. Eustatius have been estimated in the past at around a few hundred individuals, -7- Biodiversity Strategy for the Dutch Caribbean which is below the minimum viable population size. Earlier in 2013 it became clear that since 2004, population densities have declined to an average of 0.35 iguanas per square hectare across all habitats on the island, which is less than 1% of the average densities of healthy populations documented elsewhere and certain populations on St. Eustatius have even disappeared completely. Aruba Rattlesnake (Crotalus unicolor) Crotalus unicolor exists on the island of Aruba, Dutch West Indies, in a single, small, isolated population with a total distribution of approximately 76 km2. Between 1993 and 2005, 185 specimens were captured and examined, 57 specimens were telemetrically monitored, and over 3,656 field observations were catalogued. Sampled snakes occupied both desert thorn scrub and baranca (rock terrace) macrohabitats in the interior portion of the island. Conch Conch text to be written by Sabine Engel Lobster -8-