What is a sentence? - University of Hull

advertisement

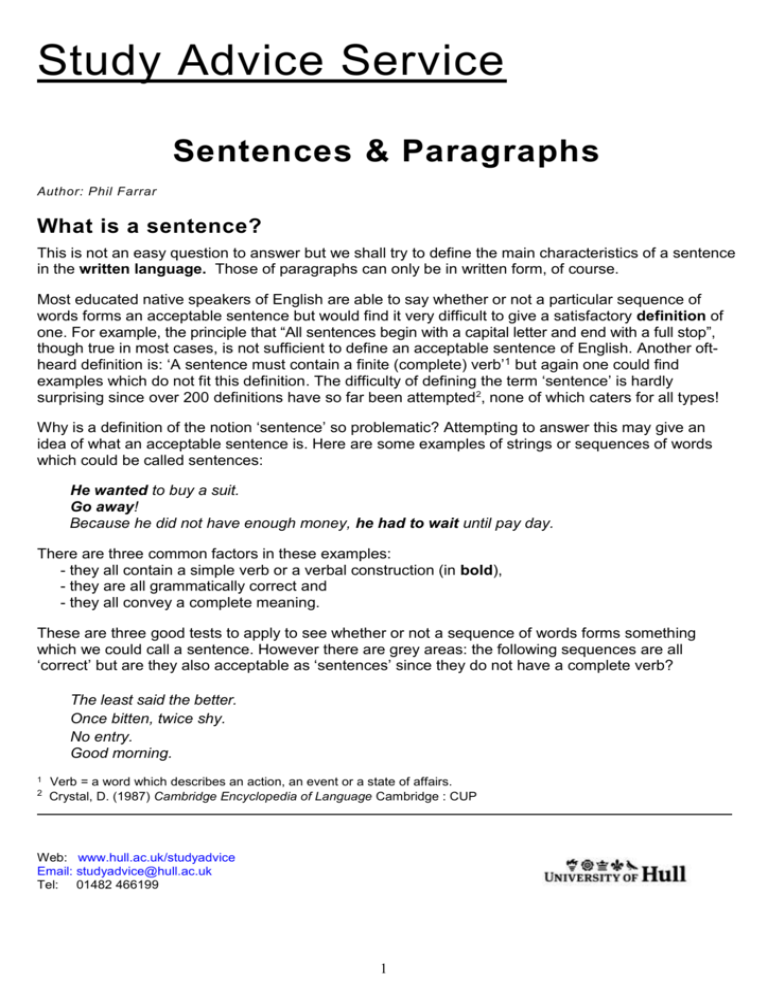

Study Advice Service Sentences & Paragraphs Author: Phil Farrar What is a sentence? This is not an easy question to answer but we shall try to define the main characteristics of a sentence in the written language. Those of paragraphs can only be in written form, of course. Most educated native speakers of English are able to say whether or not a particular sequence of words forms an acceptable sentence but would find it very difficult to give a satisfactory definition of one. For example, the principle that “All sentences begin with a capital letter and end with a full stop”, though true in most cases, is not sufficient to define an acceptable sentence of English. Another oftheard definition is: ‘A sentence must contain a finite (complete) verb’1 but again one could find examples which do not fit this definition. The difficulty of defining the term ‘sentence’ is hardly surprising since over 200 definitions have so far been attempted2, none of which caters for all types! Why is a definition of the notion ‘sentence’ so problematic? Attempting to answer this may give an idea of what an acceptable sentence is. Here are some examples of strings or sequences of words which could be called sentences: He wanted to buy a suit. Go away! Because he did not have enough money, he had to wait until pay day. There are three common factors in these examples: - they all contain a simple verb or a verbal construction (in bold), - they are all grammatically correct and - they all convey a complete meaning. These are three good tests to apply to see whether or not a sequence of words forms something which we could call a sentence. However there are grey areas: the following sequences are all ‘correct’ but are they also acceptable as ‘sentences’ since they do not have a complete verb? The least said the better. Once bitten, twice shy. No entry. Good morning. 1 2 Verb = a word which describes an action, an event or a state of affairs. Crystal, D. (1987) Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language Cambridge : CUP Web: www.hull.ac.uk/studyadvice Email: studyadvice@hull.ac.uk Tel: 01482 466199 1 These all express a clear message, are grammatically correct, start with a capital letter and end with a full stop. Some linguists suggest an answer to this question by saying that “All native speakers can recognise a well-formed utterance (a sequence of words, spoken or written)”, but whether or not it can be classified as a sentence is not always clear. So, we could say that He will arrive later this afternoon, or Later this afternoon, he will arrive. are acceptable sentences but that the following are not, since the order in which the units combine does not follow an acceptable syntactic pattern (i.e. the way the sentence is structured), or because the utterance is semantically incomplete (i.e. it does not convey a complete meaning or idea): He will later this afternoon arrive. Arrive later this afternoon he will. He later this afternoon. We can see from the above that word order is often crucial to the meaning of an utterance in English. The sentences and He knows the result He will ring with all the details are each correct and complete but simply joining the two together will not make an acceptable sentence. To achieve this, the word He will need to be deleted to avoid repetition and the addition of the word when or but is required to produce: or or When he knows the result, he will ring with all the details. He will ring with all the details when he knows the result. He will ring with all the details, but he knows the result. (The last two examples have slightly different meanings since the logical connection between the two halves of the sentence - when/but - is not the same. It is interesting to note here that, in formal written English, it is advisable not to start sentences with but and that the Present Tense is used to convey a future meaning, illustrating the fact that human language is not an exact science and not always logical - thank goodness!) So, a sentence could be defined as ‘the largest unit [of language] to which syntactic rules apply’. 1 It is a good idea, especially for non-native speakers of English, not to construct sentences which are too long in order to avoid problems with syntax2. Often, one becomes so engrossed in communicating the meaning or series of ideas that the sentence becomes jumbled or incomplete, but it may be the confusion of subject and verb, or a lack of one of these, which causes the problem. Some examples (below) showing constructional and other errors may serve to illustrate the point: 1 Crystal D. (1997) The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language Cambridge : C.U.P. p. 94 is the study of word combinations or sentence structure. 2 Syntax 2 Non -s e nte nc e Corre c te d ex a mple “Although the Consumer Act 1991 came into force, which play a key role in the new policy, but to what extent the regulation will improve the situation for consumers.” The Consumer Act came into force in 1991 and it plays a key role in the new policy, but to what extent will the regulation improve the situation for consumers? Remarks: This is really two or three sentences in one which is too far from the noun phrase to which it refers (the Consumer Act 1991). there is no main clause for the subordinate clause beginning “Although …” the modal (auxiliary) verb will should precede the subject of the main verb improve, thus changing the statement into a question the direct question (to what extent…) has no question mark Structure: [Main clause] + and + [main clause] + but + [main clause] Note that each main clause has its own complete verbal form, came into force, plays, will …improve. or: Although the Consumer Act came into force in 1991 and plays a key role in the new policy, to what extent will the regulation improve the situation for consumers? Structure: [Subordinate clause] + and + [subordinate clause] + [main clause] Here too, each clause has a complete verbal form (see above) “With the development of the economies, higher standards require for companies to meet.” With the development of economies, companies need to meet higher standards. Remarks: the second the is not needed. require is a transitive verb and has a direct object, so there is no for. here, the verb meet would mean that the companies would need to meet each other. Meet can also be transitive, in which case the sentence is incomplete and would require an object e.g. “ … to meet certain criteria.” Structure: [noun phrase] + [main clause] “This theory closely linked with the stakeholders, the underlying elements of corporate governance.” This theory is closely linked with the stakeholders (who are) the underlying elements of corporate governance. or: The development of economies requires companies to meet higher standards. Structure: [main clause] Remarks: there is no finite or tensed verb, so there is not a complete sentence. Structure: [main clause] + [relative clause] 3 “Focuses on the company, its survival closely associated with some other social parts in broader social system.” [This essay] focuses on the company. Its survival is closely associated with some other aspects of the broader social system. Remarks: the verb focuses has no subject and associated with is not a complete construction: there is no auxiliary verb. the meaning of social parts is unclear. there is repetition of the word social. Structure: [main clause] + [main clause] or: [This essay] focuses on the company, whose survival is closely associated with the broader social system. Structure: [main clause] + [relative clause] “Ethical stakeholders, that is, regardless of whether there is an improvement of financial performance, management should take account into all stakeholders’ benefits, such as human rights, public relations and environmental performance.” Regardless of whether or not there is an improvement of financial performance, management should take account of all stakeholders’ benefits … Remarks: that is is not needed. whether should be followed by or not since there is an implied comparison or alternative the phrasal verb is to take account of, not into, something (but we do say to take something into account). take account has two different subjects. Who is taking account of what? If it is the management which is taking shareholders into account, then the first two words of the ‘sentence’ are not needed either. Note that this sentence is simpler and avoids repetition of the word performance. Structure: [subordinate clause] + [main clause] Paragraphs All essays, books, reports etc are divided into paragraphs – the building blocks of an essay - and there are two good reasons for this. Firstly, a long text with no breaks is an unappealing prospect for any reader and he or she would also find it difficult to refer to any given part of it afterwards. It would have a most uninteresting appearance on the page and perhaps be difficult to follow. Secondly, dividing it into paragraphs, each of which is a collection of closely related ideas about a particular theme or idea, organises the arguments better for both the author and the reader. It clearly marks a progression in the arguments into visually obvious steps or parts. Whether the paragraph is descriptive or discursive, it is a good idea to have the first sentence give a good idea of what it will contain, thus guiding the reader along the ‘pathway’ you have devised. So, a paragraph could be said to be ‘a short passage or a collection of sentences, with a unity of content or purpose’ (Chambers Dictionary 1998). It is usually possible (and preferable) to organise 4 ideas into paragraphs. Most are of ‘medium’ length and of course there is no ‘rule’ about this, but it is often a good idea, as you might with sentences, to vary their length from time to time. One or two paragraphs might be relatively long, if the idea being described or discussed requires this, while the occasional short paragraph can be quite ‘punchy’ and memorable. Recommended reading: Arscott, D. (n.d.) Good English: the witty, in-a-nutshell, language guide. Lewes, Sussex : Pomegranate Press. (An excellent guide. Sentencing policy starts on page 5.) Cottrell, S. (2008) The Study Skills Handbook 3rd edn. Basingstoke, Palgrave. (Paragraphs section pp. 192 – 5.) Institute of Education, University of London. http://www.ioe.ac.uk/caplits/writingcentre Go to ‘Quick tips’, then ‘Paragraphing’. There is then a short one-page description of the function of sentences and paragraphs. Kirkman, N. (n.d.) The Bumper Guide to Writing University of Hull, Disability Services. (Another excellent guide, with short exercises. The section on paragraphs is on page 19.) The Open University, Skills for Study: http://www.open.ac.uk/study-strategies/ Click the Assignments section, then Dividing your work into paragraphs. The Activity sections are for OU students but the rest is very useful. Peck, J. & Coyle, M. (1999) The Student’s Guide to Writing: Grammar, Punctuation and Spelling. Basingstoke : Palgrave. (Paragraphs are discussed starting on page 63.) Teesside University, Drop-In Student Skills Centre http://dissc.tees.ac.uk/ Click the tab Sentences and Paragraphs at the top. This goes into some very useful detail and contains examples and FAQ & quiz sections. Varley, A. & Arscott, D. (n.d.) Good Essays – every student’s guide to effective writing. Lewes, Sussex: Pomegranate Press. (An excellent, witty guide to the subject and highly recommended. A short section on paragraphs is on page 20.) (Websites correct at time of publication 1.2.11) The information in this leaflet can be made available in an alternative format on request. Telephone 01482 466199 © 04/2011 5