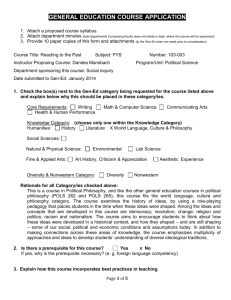

D. Maltby Fall 2015 English 1111 final project assignment

advertisement

English 1100 Final Project, D. Maltby, University of Missouri-St. Louis page 1 Final project: Dream up a Reacting To The Past game proposal This assignment is intended to bring together many elements we’ve worked on all semester: historical issues and moments, persuasion, the RTTP game concept, collaboration, writing, etc. Your assignment will involve thinking, research, and writing, but will not produce a fully developed game (that takes years!). We will work on a good bit of this together, in class. So it’s important to be here each day even if – especially if! -- you’re not as far along with your game project as you’d like. We’ll help each other! According to Nicolas W. Proctor, RTTP games need to have certain components: - “real historical setting - rich texts - multiple meetings - roles with well-developed characters - victory objectives - intellectual collisions - indeterminancy - reading, writing, and speaking - narrative structure with drama - possibilities for alternate historical outcomes - accessibility to non-specialists” (Proctor 10-11). 1. Start by thinking of an important historical moment when a decision had to be made and there was more than one issue at stake.1 The situation could be local, statewide, nationwide, or international. It needs to be a situation for which there is no RTTP game. To find out, see the Big List of Reacting Games (BLORG) https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1GkDM2eHFRl5zv0NA7tz6HZKRsK um603sl8k343MFXsc/pub?output=html. If the link doesn’t work, go to https://reacting.barnard.edu, then Curriculum, and click on a link to ‘Browse the Big List of Reacting Games (BLORG). Examples: o The Civil Rights Act of 1964 o The Equal Rights Amendment 1923 to 1979 o Red-light cameras: legal, or not? 2. Time and place. At what time and place did this moment occur? Where would the debates in your game take place? 3. What were the issues and who were the significant people? i. What groups had different opinions about these issues? 1 Remember that in the game, the situation can turn out differently from the actual event. English 1100 Final Project, D. Maltby, University of Missouri-St. Louis page 2 ii. What did those groups have to gain or lose, depending on the outcome? iii. Probably within those groups, what significant interesting people played major roles? iv. How would opinion/stake holders be grouped into two factions? v. Who will the indeterminates be (who has to be persuaded?) 4. Inherent in the issues, or surrounding them, are ‘big ideas’ that your game will focus on. Part of the process of dreaming up a game is realizing what the big ideas are. Here are examples of ‘big ideas’: - The nature of science and its relationship to modern life in an industrial society. - The tension between natural and teleological views of the world. - The nature of faith and the meaning of the Bible; how does it relate to scientific principles and methods? - How to reconcile religious identity with nation building. - How the majority can rule in a democracy while still protecting the rights of minorities. - How advancements in technology can be incorporated into workplaces when jobs are sorely needed. - How to maintain valuable traditions in a society and still move forward. - How to nurture and protect family life when both partners are active as workers or community citizens. 5. What should the students read? Find at least five relevant primary sources: a. Primary sources will mostly be written texts that present crucial information on the issues, the positions, and historical background. These texts would be assigned reading for the game. b. More thoughts on these readings: According to the RTTP Pedagogical Introduction: “[S]tudents will be obliged, in a very short period of time, to acquire a solid understanding of complex ideas and difficult texts, and also to navigate through a historical situation that is equally complicated. The readings, consequently, tend to be of two types: 1) the works of important thinkers; and 2) books and articles that establish the social or historical context. Students may be daunted by their first encounter with Plato’s Republic, the Analects of Confucius, or the sermons of Puritan ministers. These works are not easy because the ideas themselves are (literally) so thoughtful. There are good reasons why they have influenced civilizations so powerfully. Students must engage with these texts fully and in the light of the historical moment that brought them to the fore” (RTTP Pedagogical Introduction). We’ll be sharing #s 1-5 in class as you’re working on them. English 1100 Final Project, D. Maltby, University of Missouri-St. Louis page 3 WRITTEN PRODUCTS for this project (note: I strongly suggest conferences with me!) 1. Write a preliminary proposal for the game, at least 3 but no longer than 5 pages long. Include: historical moment, time/place, issue(s), groups with differing ideas about the issues, big ideas, significant interesting people, and the five primary sources. Your audience for the preliminary proposal is your classmates and me. Due on the date on the schedule. We’ll also report on these in class on that date. I’m expecting this to be a very well thought out proposal, but I also expect that the project will evolve and that the final product will emerge significantly altered from your original vision. 2. Write an annotated bibliography using the primary sources. An annotated bibliography looks much like a Works Cited page, but after each entry, you will write a paragraph of 150-300 words in which you summarize the source, explain the claim/thesis, and explain why the source is useful in the game you’re developing. Your audience for the annotated bibliography is your classmates and me. Due on the date on the schedule. See posted sample (Handouts). 3. Steps 1 and 2 will help prepare you to write an introduction to and vignette for your game. Your audience for these is your classmates, me, imaginary faculty who might teach your game, and imaginary students who may have no experience playing RTTP games. a. The introduction and vignette must total at least 4 typed, doublespaced pages, and preferably no more than 10 pages. Your muchrevised written introduction and vignette will be due during exam week. See the course schedule. b. Introduction. This is an overview of the game, including the kind of information you presented in your preliminary proposal. It will be greatly revised from that version! To get started, review the introductions to the Paterson and Greenwich Village games. c. Vignette. The vignette plunges the reader into the historical moment, setting up the situation for the students. Review the opening vignettes for the Paterson and Greenwich Village games. Here are openings from sample vignettes from two other games. Note the style in which the vignettes are written: tone, personal pronouns, scenario, etc.: “Again, your hands are fussing with your wig. You can’t help it. When you rose from your seat, walked down the long aisle, and joined the line to speak, you knew you could do it. You WOULD address the National Assembly of France. But now, you stand behind Abbé Maury and there are only three speakers ahead of him. Your heart is beating fast. The room has become stiflingly hot . . .” (Carnes and Popiel) English 1100 Final Project, D. Maltby, University of Missouri-St. Louis page 4 “Through the train’s window, smeared with grit and soot, you can barely make out the faces of the torrent of people surging along the station platform. But that swirling chaos is India: a red-turbaned Sikh, with a long, dark beard, three dark barefooted children begging for food, a Muslim woman swathed in black . . . sprinkled throughout are British soldiers in khaki, walking with that brisk, purposeful swagger that won an empire . . . “ (Embree and Carnes) ORAL PRODUCT During the last week of class, you’ll share your final game idea with the class in a polished presentation. Your audience for the presentation is your classmates and me. Your presentation should be between 10-15 minutes long and may include slides, video, handouts, etc. If you decide to use Powerpoint, see below.2 The game idea should demonstrate considerable growth and evolution since we heard your preliminary proposal. Many students revise the final introduction and vignette again after hearing feedback from the class on the presentation. This always improves the final product! Works Cited Carnes, Mark and Jennifer Popiel. “Prologue: A Night at the National Assembly.” Rosseau, Burke, and the Revolution in France, 1791. Manuscript. Norton 2.0, 2014. N.p. Embree, Ainslie T. and Mark Carnes. “The Train to Simla.” Defining a Nation: India on the Eve of Independence, 1945. New York: Barnard College and Boston: Pearson, 2006. Proctor, Nicholas W. Reacting to the Past Game Designer’s Handbook. Third edition. 2011. RTTP Pedagogical Introduction. Reacting the Past website. http://reacting.barnard.edu/sites/default/files/inline/reacting_pedagogical_ introduction-9-20-2010.pdf *Powerpoint is one of the rampant evils of the 21 st century; most people do a terrible job with it. If you MUST use it, rigorously adhere to these guidelines: - Never put your presentation text or script on the slides. - Slides should be simple but attractive. Think classy: imagine you’re presenting this to the deans of the university. - Have as few slides as possible; use them only to keep yourself and the audience organized. - Only put a few key words or appropriate visuals on the slides. - Never read your slides aloud. The audience already knows how to read. - Proofread carefully. Powerpoint errors are huge on the screen. They make you look stupid. Major points will be deducted for errors on slides or handouts. 2 English 1100 Final Project, D. Maltby, University of Missouri-St. Louis page 5