Australopithicus Afarensis

advertisement

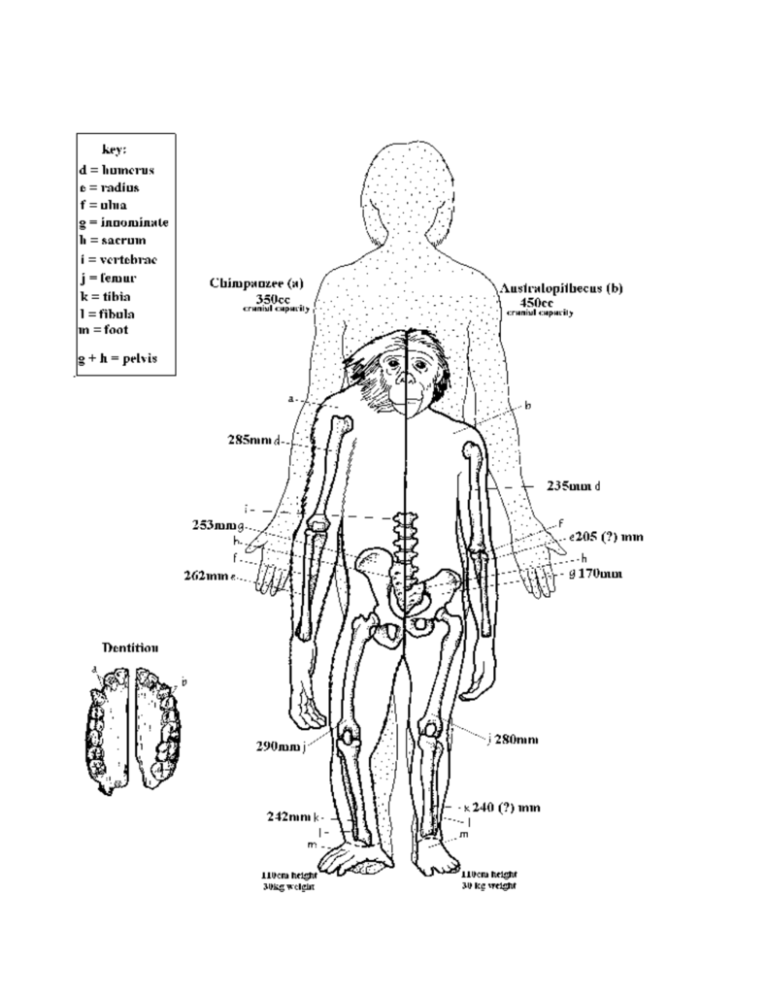

Australopithicus Afarensis: Discovering “Lucy” The badlands of the Afar Triangle, Middle Awash area near Hadar, Ethiopia in northeast Africa are a rich resource for finding early hominid fossils such as Dr. Donald Johanson and his team discovered over the course of several seasons in the mid-1970s. During the Pliocene Epoch (between 5 and 2 MaBP), this area was dominated by lakes (Zihlman 2000) and woodlands. It is along the edge of these now-dried lakes among the former woodlands that fossils can be located (Shreeve 1996). Johanson, along with colleague Tom Gray, had been mapping another locality at the Afar site. Feeling "lucky," Johanson took a short detour into another area later mapped as locality 288 and "noticed something lying on the ground partway up the slope" (Johanson, Edey 1980). This "something" turned out to be the exposed portion of a hominid arm bone. Shortly, Johanson and Gray had excavated several bones and soon realized that they were probably looking at the bones of just one individual, rather than the scattered bones of several individuals. After retrieving several pieces of jaw, they returned to their campsite to note their discovery and let the others know what they found. After three weeks of work, they had collected several hundred pieces of bone, which represented 40 percent of a single skeleton. The team knew these bones belonged to one single individual because there was no duplication of any one bone (Johanson, Edey 1980). "Later in the night of November 30th [1974], there was much celebration and excitement over the discovery of what looked like a fairly complete hominid skeleton. There was drinking, dancing, and singing; the Beatles' song 'Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds' was playing over and over. At some point during that night no one remembers when or by whom the skeleton was given the name 'Lucy.' The name has stuck". Lucy lived at a time when the Afar region was not a desert environment. Rather, it was probably woodlands and savannah. Australopithicus afarensis, not totally ape and yet not quite human, probably lived in a variety of habitats, having evolved into being bipedal as an adaptation to living in the open areas. This hypothesis would make sense because by being bipedal in the open sunlight exposes less body surface to the sun, keeping them cooler in spite of a lack of shady areas (Tattersall 1996). However, fossils are being found in the formerly woodland areas and near water, not in the open areas, making the savannah hypothesis less plausible (Shreeve 1996). And Lucy's skeleton proves that her kind was bipedal by the shape of her pelvis and the angle the femur takes from the hip socket to the knee joint. From her waist down she was hominid, and from her waist up she was still ape, as her skull was still the size of a chimpanzee. The discovery of Lucy proves that bipedalism predates big brain size (Johanson et al 1982 (a), Shreeve 1996). Lucy's skeleton, at 40 percent, is the most complete skeleton of any one individual of her age; remarkable in some ways, frustrating in others. Shell bemoans that there is no way to tell Lucy's gender because there is only one pelvic bone in existence and that one is hers, leaving no room for comparison (Shell 1991). Since the Australopithecus afarensis gave birth to offspring with ape sized brains there would have been no need for an enlarged birth canal. Johanson argues that, considering the vast collection of bones he has compared, the femoral bones show morphological identity and the size difference is attributed to sexual dimorphism (Johanson, White 1979). From bone measurements (figure 1), he was able to ascertain that Lucy probably stood three-hand-one-half feet tall and weighed sixty pounds (Johanson et al 1982-b). She was probably between twenty-five and thirty years old and showed some signs of possible arthritis (Johanson, Edey 1980). Johanson notes the "hyperstotic bone" with the worst being on vertebrae T6 and decreasing in severity through T-11 (Johanson et al 1982 b). Gender is probably not the most important aspect to the Lucy fossil as she offers much more insight into our ancient lineage. Although no other pelvis from this species has been found, other Australopithecus afarensis bones have been and reveal much about sexual dimorphism to infer her being female. Regardless of the gender argument, Lucy's pelvis tells much more; it screams "bipedal." DeWaal points out that "the most significant difference between Lucy and modern chimpanzees is found in their hips, not their craniums" (DeWaal 1997). It is Lucy's pelvic and femur structure, along with her knee joint, that are decidedly hominid. As Tattersall points out, short of having a pelvis to examine, the knee tells the most about locomotion (Tattersall 1996): "In a quadruped – an ape, say – the feet are held far apart, and each hind leg descends straight to the ground beneath the hip socket. In bipedal humans, on the other hand, the feet pass close to each other during walking so that the body's center of gravity can move ahead in a straight line. If this didn't happen, the center of gravity would have to swing with each stride in a wide arc around the supporting leg. This would be extremely clumsy and inefficient, wasting a lot of energy. So in bipeds, both femora angle in from the hip joint to converge at the knee; the tibiae then descend straight to the ground. In the human knee joint, this adaptation shows up in the angle – known as the "carrying angle" – that is formed between the long axis of the femur and tibia." The "carrying angle" can also be stated as "weight bearing axis" as shown below. The chimpanzee, which is a quadruped, has a femur that comes straight out of the hip socket, while Lucy and the modern human exhibit the bipedal carrying angle. Whether Lucy was completely terrestrial is a matter of debate. Some (Shreeve 1996, Tattersall 1996, Zihlman 2000) believe that she maintained some vestiges of her arboreal ancestry by climbing trees at night to seek shelter from predators during sleep periods, to eat fruits and leaves of trees and sometimes to scavenge a kill which is stored for "safekeeping" by predators (Tattersall 1996). There has been no evidence of tool making nor is there clear evidence of meat eating. It is plausible that Lucy and her kind used tools such as branches that would have decayed by now. This supposition is possible because chimpanzees make and use rudimentary tools for "fishing" for termites and leaves as sponges for drinking after a hard rain (Goodall 1986). Johanson's discovery of Lucy is significant in our understanding of human evolution because she is the oldest, most complete erectwalking human ancestral skeleton found to date (Johanson, Edey 1980). In addition to having characteristics halfway between ape and hominid, she proves that bipedalism was prevalent long before enlarged brain size and dispels the belief that humans became bipedal to accommodate their capacity for tool making and the need to have their hands free for their tools and the kills they can make with those tools. Lucy's skeleton was housed in a custom made box lined with yellow foam with cutouts for each bone. Johanson kept her in a safe for five years while he was with the Cleveland Museum. She has since been returned to Ethiopia and is housed at the National Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa (Johanson website). It is generally accepted that hominids diverged from the apes between 6 and 5 MaBP. Australopithecus afarensis led to 2 further divergences, the robust australopithecines that died out, and the gracile line leading eventually to us (Johanson, White 1979) figures a & b.