Literature review - Foundation Years

advertisement

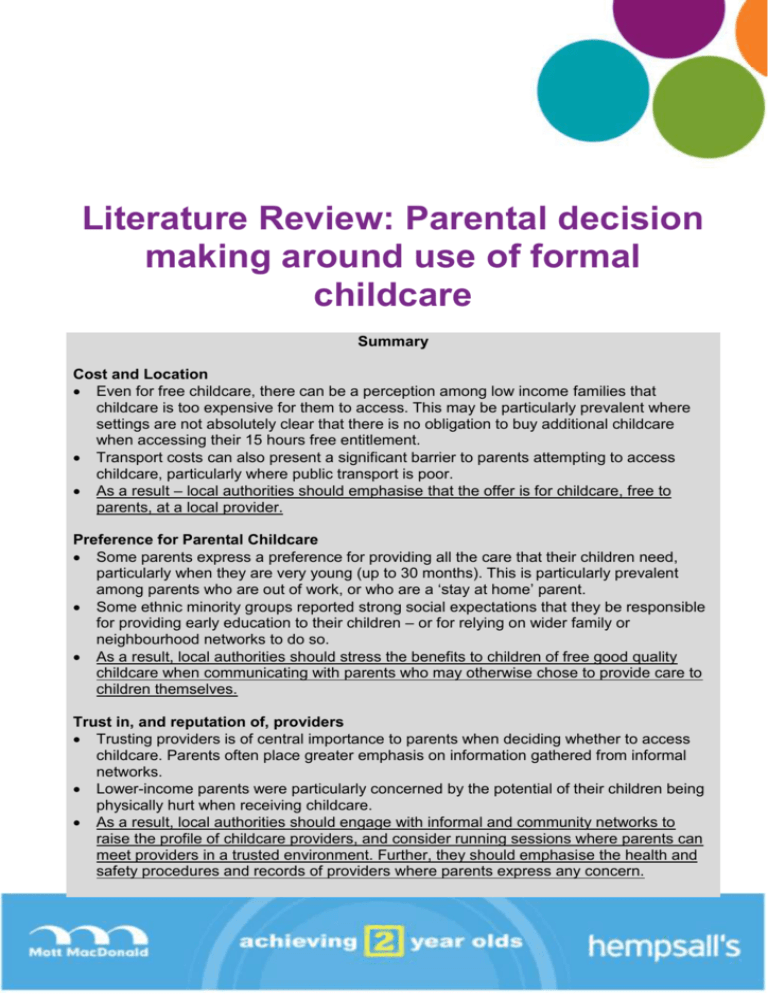

Literature Review: Parental decision making around use of formal childcare Summary Cost and Location Even for free childcare, there can be a perception among low income families that childcare is too expensive for them to access. This may be particularly prevalent where settings are not absolutely clear that there is no obligation to buy additional childcare when accessing their 15 hours free entitlement. Transport costs can also present a significant barrier to parents attempting to access childcare, particularly where public transport is poor. As a result – local authorities should emphasise that the offer is for childcare, free to parents, at a local provider. Preference for Parental Childcare Some parents express a preference for providing all the care that their children need, particularly when they are very young (up to 30 months). This is particularly prevalent among parents who are out of work, or who are a ‘stay at home’ parent. Some ethnic minority groups reported strong social expectations that they be responsible for providing early education to their children – or for relying on wider family or neighbourhood networks to do so. As a result, local authorities should stress the benefits to children of free good quality childcare when communicating with parents who may otherwise chose to provide care to children themselves. Trust in, and reputation of, providers Trusting providers is of central importance to parents when deciding whether to access childcare. Parents often place greater emphasis on information gathered from informal networks. Lower-income parents were particularly concerned by the potential of their children being physically hurt when receiving childcare. As a result, local authorities should engage with informal and community networks to raise the profile of childcare providers, and consider running sessions where parents can meet providers in a trusted environment. Further, they should emphasise the health and safety procedures and records of providers where parents express any concern. Lack of information and awareness A significant proportion of ethnic minority parents reported not receiving enough information about childcare in their area – with Asian families receiving the least information, and Black families reporting the highest dissatisfaction with both the quality and quantity of available childcare. Parents reported that the information they did receive was also hard to understand, particularly where there was a language barrier, and did not catch the eye. As a result, local authorities should engage with informal networks to disseminate information about childcare, and ensure all communication is undertaken in plain English, and in eye-catching form, illustrated by images and pictures. The importance of child social development Parents often drew a distinction between children ‘learning’ and ‘playing’ – and were often alienated by references to ‘formal childcare’. Though parents had different expectations of childcare and which it should provide, complex language in government communications often lowered parents views of the childcare on offer. As a result, local authorities should ensure that they communicate simply, and stress both the important social and education aspects of childcare – and use pictures to emphasise this point, where possible. Cost and location The cost of childcare is often quoted as being one of the major barriers for parents to access childcare (Ben-Galim, 2011, Speight et al. 2010). Looking in more depth at this the cost was not only a barrier in terms of affordability, but also in that it created a perception that childcare was unaffordable, and discouraged parents from trying to access it. Indeed, families experiencing the highest level of multiple disadvantage were more negative about the affordability of local childcare than those in better circumstances (Speight et al. 2010). There was also evidence that parents not accessing from childcare for 3 and 4 year olds, were unaware that it was provided by the government for free – and that no additional costs were attached. (Speight et al. 2010). Whilst the cost was mentioned as a problem the location of the available childcare was also frequently referenced with many parents lacking suitable transport to get to the provision or not being to take time out of their days to travel long distances. It was found that to support parents to use services they needed to be close to home, have good transport links to get to the services, fit with the primary school hours and offer flexibility in its arrangements (BenGalim, 2011). Alternatively when describing what they consider to be their ‘ideal’ childcare environment parents said that they were primarily looking for warm, friendly staff who relate well to children with the ideal location being close to the parental home or to the grandparents, so that they could pick up the children if the parents were unavailable (Roberts 2008). Preference for parental childcare A preference for parental childcare has been often presented as one of the core reason why parents decided not to use childcare. This may have been due to the parent’s family life and values, or opinions about the childcare available in their local area. In one study Smith found this to be the overwhelming reason as to why parents chose not to use childcare compared to the trust, quality, transport problems and a previous bad experience which were far less frequent reasons given (Smith et al. 2010) this was also a reason for parents who chose not to use wraparound care (Speight et al. 2010). Parental preference to care for their children themselves also figured prominently In Speight et al. 2010 it was found that amongst the reasons why parents didn’t use childcare was because parents preferred to look after child(ren), that their children preferred to be at home and reported that they had no need to be away from their child(ren) (Speight et al. 2010). This was the main reason why families suffering multiple disadvantage, low income families and BME families in particular had chosen to not use wraparound care or nursery provision and was one of the most common reason why parents didn’t take up the free three and four year old entitlement (Speight et al. 2010). The age of the child also played a role in this. In Ben-Galim 2011 parents were asked at what age they considered early years provision was appropriate. Many were resistant to the idea of their child attending in a formal setting before the age of two, preferring to leave their children with family members if they were not available themselves. Most felt that in the first two years of a child’s life, time spent bonding with immediate and then extended family was of overriding importance (Ben-Galim, 2011). Generally, parents responded that formal childcare was appropriate from about the age of two or two-and-a-half, at which point they felt it was important for their child to start interacting with other children. From the age of two or three, playing and spending time with other children were considered to be important, but not education per se. Once the child reached three, parents thought learning became more important, in preparation for school (Ben-Galim, 2011). This was also found to be the case in other research (Speight et al. 2010). It was seem that parents felt uncomfortable leaving their children alone – especially at an age where they couldn’t report back to them whether they enjoy the service (Roberts, 2008). In addition, in families where English was a second language some were worried about very young children not being able to make themselves understood within a formal care setting because the children often spoke a hybrid of English and their parents’ or grandparents’ mother tongue language (Roberts 2008). Some groups of parents are particularly likely to report that they did not need to use childcare because they didn’t need to be away from their child (Speight et al. 2010). Culturally, Muslim mothers reported that they are expected to be their child’s primary carer. Thus, the notion of ‘childcare’ was an alien concept, particularly for Bangladeshi mothers, most of whom were not working (Roberts 2008). For low income parents wanted to spend as much time as possible with their children and they tended to see work as a means to an end. They were very disapproving of ‘career people’ who (they perceive) have children and pay someone else to bring them up. This view is further illustrated by the fact that many said the government should be encouraging parents to stay home with their children when the children are young (Roberts 2008). In the cases where those parents who had a preference for parental care did require support outside of the household they would turn to extended family member. For Muslim mothers any social occasions they attended in the evening would be a family outing (to visit relatives, or to a wedding etc.) so they had no need for paid babysitters. Plus, if the need ever arose, the Pakistani and Bangladeshi mums all came from large families so relatives were always available to help. They also spoke of the stigma attached to using formal childcare within the Muslim community and the risk of offending family members by seeking professional care (Roberts 2008). It was also shown that for many families there was predominance of strong extended families networks – with many families having older generations either living in the house or living close by. This shows the important role of family and why so many parents turn to them to help with childcare duties (Roberts 2008). Not only was family care considered by many to be the first port of call for care, it was also considered the best form of care for children. Family members were seen as an extensions of parental care (‘the next best thing to being there myself’), while using childcare was seen as leaving one’s child with a ‘stranger’. It was seen that family members meant the child would be treated as ‘one of their own’, because children enjoy spending time with their family, especially grandparents are seen as having the experience of raising a child, it is convenient and free. It also removed concerns about whether the religious beliefs of the child (would halal or vegetarian food be available) would be met in formal care (Roberts 2008). However, parents also understood that this may mean that children would lose out on the interaction with other children in most family care settings, children were less likely to do any structure or stimulating activities with family members and that parents often felt (or were made to feel) guilty about asking family members to babysit (Roberts 2008). Amongst these families young children were most likely to receive childcare for reasons related to their development or enjoyment. The more disadvantaged children experienced the less likely they were to receive childcare for economic reasons i.e. so that they parents could work or study and instead more likely to receive childcare for reasons related to parental time i.e. so that parents could do domestic activities, socialise, or look after other children (Speight et al. 2010). Trust in, and reputation of, providers The biggest influence on childcare provider selection were the reputation of the provider and finding a provider that was convenient – a further reason provided by half of parents who did use childcare and especially relevant to those parents with a child aged 0-2 (Speight et al. 2010). Overall there was most trust in government-run nurseries, schools and schools clubs and least trust in childminders (those not known personally to the family) although there was some parents willing to change this view if there was better explanation of the registration process to show the trustworthiness of childminders (Roberts 2008). Research on choice (Duncan et al 2003, Carling et al 2002, Lowe & Weisner 2004, Meyers & Jordan 2006) show that parental decisions around childcare are a complex mixture of practical and moral concerns, social relations are as least as important as economic relations. For many, trust was a key issue in not choosing childcare (Bell et al 2005). Many parents struggle with trust issues and the possible consequences of leaving their child with a ‘stranger’ - some parents said they would blame themselves for making a bad choice if their child were harmed or mistreated in any way. (Roberts 2008). Parents from lower income groups were more fearful about their children’s physical safety than their middle class counterparts, and commonly opted for nurseries, rejecting childminders unless they were previously known to them. This was striking throughout the sample (Vincent & Ball 2006, Vincent et al 2008a). These mothers tended to stress the risk of emotional neglect in nurseries whereas for the working class mothers the primary concern was the possibility of physical neglect or harm from childminders. It was very clear that the working class respondents distrusted, even feared, unknown private spaces (such as a childminder’s house), and individual, unknown carers (Lowe & Weisner 2004 also find fears of ‘stranger’ carers in the US amongst working class families). Some working class respondents did not feel comfortable leaving their child with another carer, even if in a formal regulated setting, and cited lack of trust as the explanation for this (Duncan et al 2004). Lack of information and awareness As well as location and affordability, a lack of available information has been noted as a key barrier preventing parents from accessing childcare (Bell at al 2004). Asian parents were least likely to have received any information on childcare but were also significantly more likely than White or Black parents to say that ‘about the right amount’ of information was available to them. This could reflect a lower demand for such information among Asian parents, who are the least likely of all the groups to be using (formal) childcare. Black parents were least positive about the amount of childcare information available to them, which could reflect their higher demand for childcare or the relative shortage of childcare in more deprived areas (Bell et al. 2005). Evidence has identified that there can often be a lack of awareness around cultural difference between and within minority ethnic groups from local government and childcare providers. The ‘one size fits all’ BME label can be unhelpful as it blinded some service providers to the different values, cultures and needs of distinct minority ethnic groups, despite examples of best practice of working with different communities being available (Bell et al. 2005). For the current free entitlement, low awareness of the scheme was a particular barrier for highly disadvantaged families who had less awareness of the offer than less or nondisadvantaged families (Speight et al. 2010). The evidence suggests that parent networks are positive to engage potential new users (Ben-Galim, 2011) by working through the positive benefits of word of mouth but do not provide a complete solution. They were found to offer an important source of mutual support and a source of capacity building for parents to involve themselves in childcare (Beirens et al. 2006). Parent’s meetings and parents’ associations have also been found to have a positive effect and had helped give a voice to otherwise marginalised minority ethnic parents (Blair and Bourne, 1998. Ofsted 2004b). The lack of information is important not only for the understanding of the offer but because it can link to wider perceptions about quality and availability. Parents from the most disadvantaged families were somewhat more likely to hold the view that there were not enough childcare places than families in better circumstances. The research found that those parents who said there was too little information available to them were much more likely to say that there were not enough childcare places in their local area than those who felt satisfied with the amount of information they had received (Speight et al. 2010). Similarly, the most disadvantaged parents were less positive about the quality of childcare available in their area (Speight et al. 2010). Asian parents were most likely to say that they did not know about either the number or the quality of childcare places available, reflecting the fact that they were least likely to have received any childcare information (Bell et al 2005). These findings are consistent with previous research that found that families living in deprived areas tended to overestimate the difficulties or arranging formal childcare for their pre-school children (Smith et al. 2007). It was found that parents wanted information on what services are available in the area should come to parents from the local authority should be summarised, simple literature should be produced in plain English with explanatory illustrations and photos in leaflets and made available in everyday places (shopping centres, supermarkets, doctors surgeries, libraries) and online (Ben-Galim, 2011, Kazimirski et al 2008, McNeil 2010). Language barriers The additional barrier of communication where language difficulties exist means that when information is provided to parents it is not always understood (Beirens et al. 2006). The term ‘childcare’ is often equated with formal childcare among families with English as a second language. They often see childcare as something not relevant to their lives, because they associate it with working parents and those with no family members around to help. Low-income parents, on the other hand, generally have close relationship with their extended family and family care was by far the preferred option across the board (Roberts 2008). Whilst ‘childcare’ is sometime constructed as providing a double benefit – good for them, good for you – low income audience sees childcare as a service for parents who put their own needs first. They believe staying home with their children is a positive choice (Roberts 2008). The way in which the educational benefits of childcare are expressed in terms of ‘goals’, ‘stages’, and targets’ in government literature is alienating for low-income parents, who prefer to think of pre-schoolers learning at their own pace and in a fun way (Roberts 2008). It has been found that there should be no suggestions that formal care is better for children’s progress at school than informal care, as parents are likely to reject this notion (Roberts 2008). The importance of child social development For many low income families ‘childcare’ equated to ‘formal childcare’ - they were unfamiliar with the concept of ‘formal childcare’ when it was referred to in those terms. The word ‘formal’ suggest something strict and structured, whilst ‘childcare’ evokes images of play, fun and informality. Due to a genuine lack of understanding of the term, respondents assumed such care would be out of their reach, both in financial and social class terms (Roberts 2008). For many low income families the main barrier to using formal childcare was not so much lack of information, but a lack of connection with the concept. Childcare was perceived to have little personal relevance to their lives because they saw it as something used by working mums or mums with a career, or people who put work before their family. (Roberts 2008). Parents were concerned that pre-school children should learn in a fun – not academic – way. By contrast, the official discourse assumes its readers value “educational goals” and “development stages”. The act of choosing childcare is constructed as closely related to the future success of the child where as many low income families more closely associate childcare with fun activities (Roberts 2008). One of the most common themes across families – including minority ethnic and traveler communities -for their wish to use childcare was that they saw childcare as beneficial for a child’s development, although again the issue of the age of the child was present (Waldfogel and Garnham 2008, Speight et al 2009). Most parents recognized that through interacting with other children their child would learn and develop confidence and social skills, learning to share, making friends, getting to know children they would later go to school with, fostering independence, and preparation for other environments, especially school (Ben-Galim, 2011, Speight et al 2010). Other parents, particularly those from minority ethnic backgrounds, stressed the importance of childcare as an opportunity for their children to mix with children from different backgrounds and for children to improve their English language skills as being particularly important for their children (Ben-Galim, 2011, Williams and Churchill 2006). However, again the issue of adequate information was present with some parents showing a lack of understanding of the benefits of childcare for the child (Roberts 2008). Bibliography Katz, I. & Pinkerton, J. (2003). Evaluating Family Support: Thinking Internationally, Thinking Critically. Chichester: Wiley & Sons Gillies, V, (2008). Perspectives on parenting responsibilities: Contextualising Values and Practices. Journal of Law and Society, Volume 35, No 1 pp95-118 Katz, I., La Placa,V. & Hunter, S. (2007). Joseph Rowntree Foundation Outreach to Children and Families, A Scoping Study, DCSF, June 2009 Early Education Pilot for Two Year Old Children, Evaluation, Ruth Smith, Susan Purdon, Vera Schneider, Ivana La Valle, Ivonne Wollny, Rachael Owen and Caroline Bryson, Sandra Mathers, Kathy Sylva, Eva Lloyd, DCSF, 2009 Understanding Attitudes to Childcare and Childcare Language among Low Income Parents, Karen Roberts, DCSF, 2008 Li, Y, Savage, M & Pickles, A. (2003) Social Change, Friendship and Civic Participation Sociological Research Online, 8, (4), <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/8/4/li.html Lowe, E. & Weisner T. (2004) 'You have to push it- who's gonna raise your kids?': situating child care and child care subsidy in the daily routines of lower income families, Children and Youth Services Review, 26 (2) 143-171. Carling, A., Duncan, S. and Edwards, R. (2002) Analysing Families: Morality and Rationality in Policy and Practice, London, Routledge. Meyers, M & Jordan, L. (2006) Choice and accommodation in parental child care decisions Community Development: Journal of the Community Development Society, 37, 2: 53-70 Duncan, S., Edwards, R., Reynolds, T., & Alldred, P. (2003) Motherhood, paid work and partnering: values and theories, Work, Employment and Society, 17 (2): 309-330. Duncan, S., Edwards, R., Reynolds, T., & Alldred, P. (2004) Mothers and childcare: policies, values and theories, Children and Society, 18: 254-65. Vincent, C. & Ball, S. J. (2006) Childcare, Choice and Class Practices. London, Routledge. Vincent, C., Ball, S. J. & Braun, A. (2008b) „It‟s like saying “coloured”:understanding and analysing the urban working classes. The Sociological Review 56 (1): 61-77. Vincent, C., Braun, A. & Ball, S. (2008a) Childcare, Choice and Social Class, Critical Social Policy, 28, (1) 5-26 Local links, local knowledge: Choosing care settings and Schools, Carol Vincent, Annette Braun and Stephen Ball, Institute of Education, University of London, 2009 Smith, R., Poole, E., Perry, J., Wollny, I., Reeves, A., Coshall, C., d’Souza, J., and Bryson, C. (2010) Childcare and Early Years Survey of Parents 2009. DfE Research Report. RR-054 London:DfE Speight, S., Smith, R., and Lloyd, E., with Coshall, C. (2010) Families Experiencing Multiple Disadvantage: Their Use of and Views on Childcare Provision, DCSF Research Report DCSF-RR191. London: DCSF. Stratford, N., Finch, S. and Petick, J. (1997) Survey of Parents of Three and Four Year Old Children and their Use of Early Years Services. DfES Research Report 31. Nottingham: DfES Publications . Smith, R., Speight, S. and La Valle, I. (2009a) Fitting It All Together: How Families Arrange Their Childcare and the Influence on Children’s Home Learning, DCSF Research Report RR090. Nottingham: DCSF Publications. Page, J., Whitting, G., and Mclean, C. (2007) Engaging Effectively with Black and Ethnic Minority Parents in Children’s and Parental Services. DCSF Research Report DCSF-RR013. London: DCSF, Oppenheim, C. (2007) Increasing the take-up of formal childcare among Black and Minority Ethnic Families and families with a disabled child. Report to the Department for Education and Skills. www.dcsf.gov.uk/everychildmatters/download/?id=384 (accessed 21 August 2010). Box, L., Bignall, T., & Butt, J (2001) Supporting parents through provision of childcare, London: Race Equality Unit Ben-Galim, D., (2011) Parent’s at the Centre, IPPR Ben-Galim, D., (2011) Parent’s at the Centre – Slide Pack for Practitioners, IPPR Department for Children, Schools and Families (2008) Sure Start Communication Toolkit, London: Department for Children, Schools and Families National Children’s Bureau (2010) principles for Engaging with Families, London: National Children’s Bureau Daycare Trust, Benefits of a parent champions scheme. Available at: http://www.daycaretrust.org.uk/pages/benefits-of-a-parent-champions-scheme.html