Medieval Art and Architecture: 800 – 1500 CE

advertisement

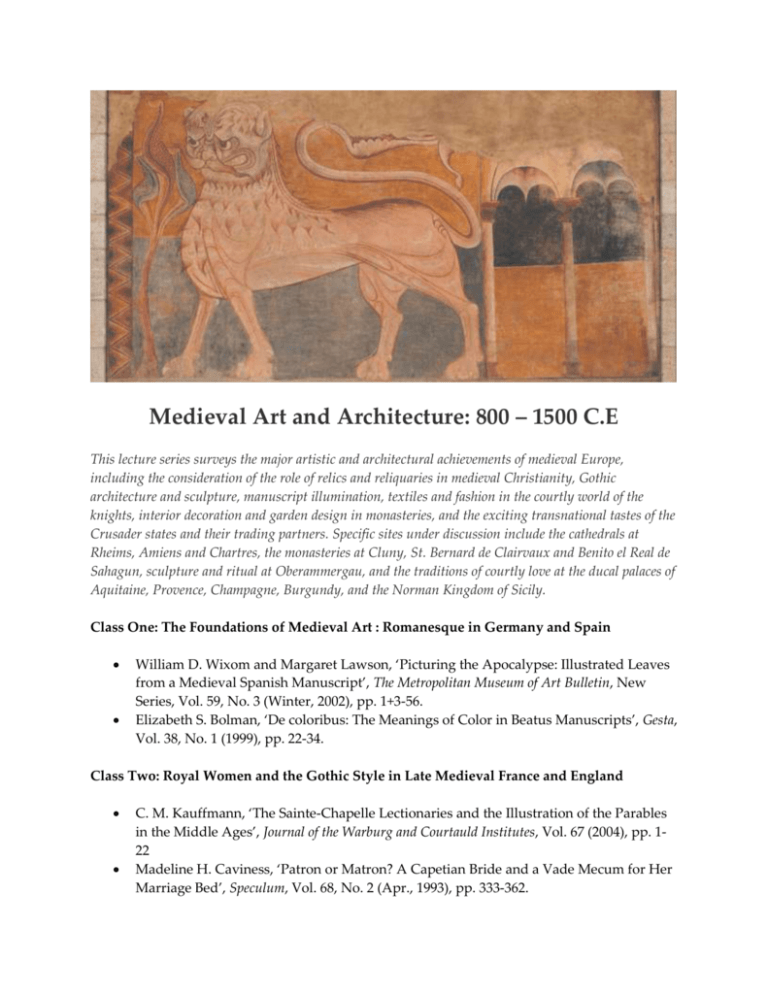

Medieval Art and Architecture: 800 – 1500 C.E This lecture series surveys the major artistic and architectural achievements of medieval Europe, including the consideration of the role of relics and reliquaries in medieval Christianity, Gothic architecture and sculpture, manuscript illumination, textiles and fashion in the courtly world of the knights, interior decoration and garden design in monasteries, and the exciting transnational tastes of the Crusader states and their trading partners. Specific sites under discussion include the cathedrals at Rheims, Amiens and Chartres, the monasteries at Cluny, St. Bernard de Clairvaux and Benito el Real de Sahagun, sculpture and ritual at Oberammergau, and the traditions of courtly love at the ducal palaces of Aquitaine, Provence, Champagne, Burgundy, and the Norman Kingdom of Sicily. Class One: The Foundations of Medieval Art : Romanesque in Germany and Spain William D. Wixom and Margaret Lawson, ‘Picturing the Apocalypse: Illustrated Leaves from a Medieval Spanish Manuscript’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 59, No. 3 (Winter, 2002), pp. 1+3-56. Elizabeth S. Bolman, ‘De coloribus: The Meanings of Color in Beatus Manuscripts’, Gesta, Vol. 38, No. 1 (1999), pp. 22-34. Class Two: Royal Women and the Gothic Style in Late Medieval France and England C. M. Kauffmann, ‘The Sainte-Chapelle Lectionaries and the Illustration of the Parables in the Middle Ages’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 67 (2004), pp. 122 Madeline H. Caviness, ‘Patron or Matron? A Capetian Bride and a Vade Mecum for Her Marriage Bed’, Speculum, Vol. 68, No. 2 (Apr., 1993), pp. 333-362. Class Three: Burgundian Splendour: The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry Michael Camille, ‘The "Très Riches Heures": An Illuminated Manuscript in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Autumn, 1990), pp. 72-107. Catherine Reynolds, ‘The 'Très Riches Heures', the Bedford Workshop and Barthélemy d'Eyck’, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 147, No. 1229 (Aug., 2005), pp. 526-533. Class Four – Gold in the Darkness: Hiberno-Saxon Manuscripts Paul Meyvaert, ‘The Book of Kells and Iona’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 71, No. 1 (Mar., 1989), pp. 6-19. Lawrence Nees, ‘Reading Aldred's Colophon for the Lindisfarne Gospels’, Speculum, Vol. 78, No. 2 (Apr., 2003), pp. 333-377. Class Five – The Carolingian “Renaissance”: Charlemagne and his Legacy Lawrence Nees, ‘On Carolingian Book Painters: The Ottoboni Gospels and Its Transfiguration Master’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 83, No. 2 (Jun., 2001), pp. 209-239. Robert Deshman, ‘Another Look at the Disappearing Christ: Corporeal and Spiritual Vision in Early Medieval Images’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 79, No. 3 (Sep., 1997), pp. 518546. John Lowden, ‘Observations on Illustrated Byzantine Psalters’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 70, No. 2 (Jun., 1988), pp. 242-260. Henry Maguire, ‘Style and Ideology in Byzantine Imperial Art’, Gesta, Vol. 28, No. 2 (1989), pp. 217-231. Class Six – Norman Art and Architecture Laura Ashe, ‘Mutatio dexteræ Excelsi: Narratives of Transformation after the Conquest’, The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Vol. 110, No. 2 (March 28, 2011), pp. 141-172. Charles E. Nicklies, ‘Builders, Patrons, and Identity: The Domed Basilicas of Sicily and Calabria’, Gesta, Vol. 43, No. 2 (2004), pp. 99-114.