The Case - WordPress.com

advertisement

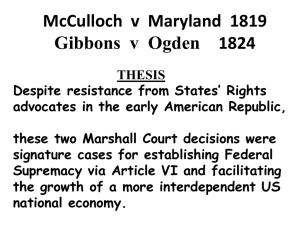

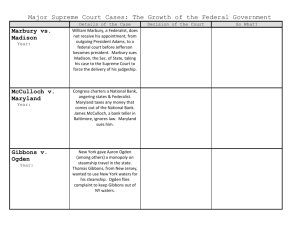

Gibbons v Ogden One of the enduring issues in American government is the proper balance of power between the national government and the state governments. This struggle for power was evident from the earliest days of US government and is the underlying issue in the case of Gibbons v. Ogden. In 1808, Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston were granted a monopoly from the New York state government to operate steamboats on the state's waters. This meant that only their steamboats could operate on the waterways of New York, including those bodies of water that stretched between states, called interstate waterways. This monopoly was very important because steamboat traffic, which carried both people and goods, was very profitable. Aaron Ogden held a Fulton-Livingston license to operate steamboats under this monopoly. He operated steamboats between New Jersey and New York. However, another man named Thomas Gibbons competed with Aaron Ogden on this same route. Gibbons did not have a Fulton-Livingston license, but instead had a federal (national) coasting license, granted under a 1793 act of Congress. Naturally, Aaron Ogden was upset about this competition because according to New York law, he should be the only person operating steamboats on this route. Ogden filed a complaint in the Court of Chancery of New York asking the court to stop Gibbons from operating his boats. Ogden claimed that the monopoly granted by New York was legal even though he operated on shared, interstate waters between New Jersey and New York. Ogden's lawyer said that states often passed laws on issues regarding interstate matters and that states should be able to share power with the national government on matters concerning interstate commerce or business. New York's monopoly, therefore, should be upheld. Gibbons' lawyer disagreed. He argued that the U.S. Constitution gave the national government, specifically Congress, the sole power over interstate commerce. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution states that Congress has the power "[t]o regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States. . . ." Gibbons' lawyer claimed that if the power over interstate commerce were shared between the national and state governments, the result would be contradictory laws made by both governments that would harm business in the entire nation. The Court of Chancery of New York found in favor of Ogden and issued an order to restrict Gibbons from operating his boats. Gibbons appealed the case to the Court of Errors of New York, which affirmed the lower court's decision. Gibbons appealed the case to the Supreme Court of the United States. The key question in this case is who should have power to determine how interstate commerce is conducted: the state governments, the national government, or both. This was no small matter, as the nation's economic health was at stake. Before the U.S. Constitution was written, the states had most of the power to regulate commerce. Often they passed laws that harmed other states and the economy of the nation as a whole. For instance, many states taxed goods moving across state borders. Though many people acknowledged that these were destructive policies, they were reluctant to give too much power over commerce to the national government. The trick was to find a proper balance. Chief Justice John Marshall's decision in this case was a precedent for determining what that balance should be and has far-ranging effects to this day. McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) In 1791, the U.S. government created the first national bank for the country. During this time, a national bank was controversial because people had different opinions about what powers the national government should have. Alexander Hamilton believed that the national government had the power to create a new national bank. Thomas Jefferson believed that the national government did not have such a power. When Thomas Jefferson was president, he did not renew the national bank's charter. After the War of 1812, President James Madison decided that the country needed a national bank, and he asked Congress to create a Second Bank of the United States in 1816. After President Madison approved the bank, many branches were opened throughout the country. Many states did not want the new bank branches to open. There were several reasons why the states opposed these national banks. They competed with the state banks, many national bank managers were thought to be corrupt, and the states believed that the national government was getting too powerful. Maryland tried closing down the Baltimore branch of the national bank by passing a law that forced all banks that were created outside of the state pay a $15,000 tax each year. James McCulloch, who worked at the Baltimore Branch, refused to pay the tax. The State of Maryland took McCulloch to court saying that Maryland had the power to tax any business in its state. Luther Martin, a lawyer for Maryland, said that if the national government had the power to regulate state banks, then Maryland had the power to regulate national banks. He also said that the Constitution does not give Congress the power to create a national bank. After McCulloch was convicted of violating the tax statute and fined $2,500, he appealed the court's decision to the Maryland Court of Appeals. His lawyer argued that creating a national bank was a "necessary and proper" job of Congress. He stated that many of the powers of the national government are not written in the Constitution, but are necessary for the national government to do its job. Also, he claimed that Maryland could not place a tax on the national bank because the tax would not let the national bank do its job. The Maryland Court of Appeals agreed with the lower court's decision. McCulloch then appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, led by Chief Justice John Marshall. Marbury v. Madison (1803) Thomas Jefferson, a member of the Republican Party, won the election of 1800. Before Jefferson took office, John Adams, the outgoing President who was a Federalist, quickly appointed 58 members of his own party to fill government jobs created by Congress. He did this because he wanted people from his political party in office. It was the responsibility of Adams' Secretary of State, John Marshall, to finish the paperwork and give it to each of the newly appointed officials. Although Marshall signed and sealed all of the papers, he failed to deliver 17 of them to the appointees. Marshall thought his successor would finish the job. But when Jefferson became President, he told his new Secretary of State, James Madison, not to deliver some of the papers. Those individuals couldn't take office until they actually had their papers in hand. Adams had appointed William Marbury to be justice of the peace of the District of Columbia. Marbury was one of the last-minute appointees who did not receive his papers. He sued Adams' Secretary of State, James Madison, and asked the Supreme Court of the United States to issue a court order requiring that Madison deliver his papers. Marbury argued that he was entitled to the job and that the Judiciary Act of 1789 gave the Supreme Court of the United States original jurisdiction to issue a writ of mandamus, which is the type of court order he needed. When the case came before the Court, John Marshall — the person who had failed to deliver the commission in the first place — was the new Chief Justice. The Court had to decide whether Marbury was entitled to his job, and if so, whether the Judiciary Act of 1789 gave the Court the authority it needed to force the Secretary of State to appoint Marbury to his position. Dartmouth College v. Woodward The Case Dartmouth College’s charter was granted by King George III of the Kingdom of Great Britain on December 13, 1769. In 1815, over thirty years after the conclusion of the American Revolution, the legislature of New Hampshire attempted to invalidate Dartmouth's charter in order to convert the school from a private to a public institution. The trustees of the College objected, and thus sought to have the attempted actions of the legislature declared unconstitutional. The trustees retained Dartmouth alumnus Daniel Webster, a New Hampshire native who would later become a U.S. Senator from Massachusetts and Secretary of State under President Millard Fillmore. Webster was hired to argue the college's case in court against William H. Woodward, the state-appointed secretary of the new board of trustees. Webster's speech in defense of Dartmouth (which he described as "a small college," adding, "and yet there are those who love it") was so moving that it reportedly brought tears to Chief Justice Marshall's eyes. Dartmouth College v. Woodward The Supreme Court’s Decision The decision, handed down on February 2, 1819, ruled in favor of the College and invalidated the act of the New Hampshire legislature; which, in turn, allowed Dartmouth to exist as a private institution and take back its buildings, seal, and charter. The majority opinion was, predictably, written by Marshall. This again affirmed Marshall's belief in the sanctity of a contract (also seen in Fletcher v. Peck; 1810). Dartmouth at the time was not a popular decision. When the United States Supreme Court ruled for Dartmouth, a public outcry ensued. Jefferson comiserated with New Hampshire Governor Plumer, writing in essence that the earth belongs to the living. State courts and legislatures, supported by the people, declared that state governments had an absolute right to amend or repeal a corporate charter. However, today Dartmouth is considered to be one of the most important Supreme Court rulings, strengthening the Contract Clause and limiting the power of the States to interfere with private institutions' charters. The decision protected contracts against specifically state encroachments. More recently it has had the effect of safeguarding business enterprises from state governments’ dominion.