peer learning for teachers

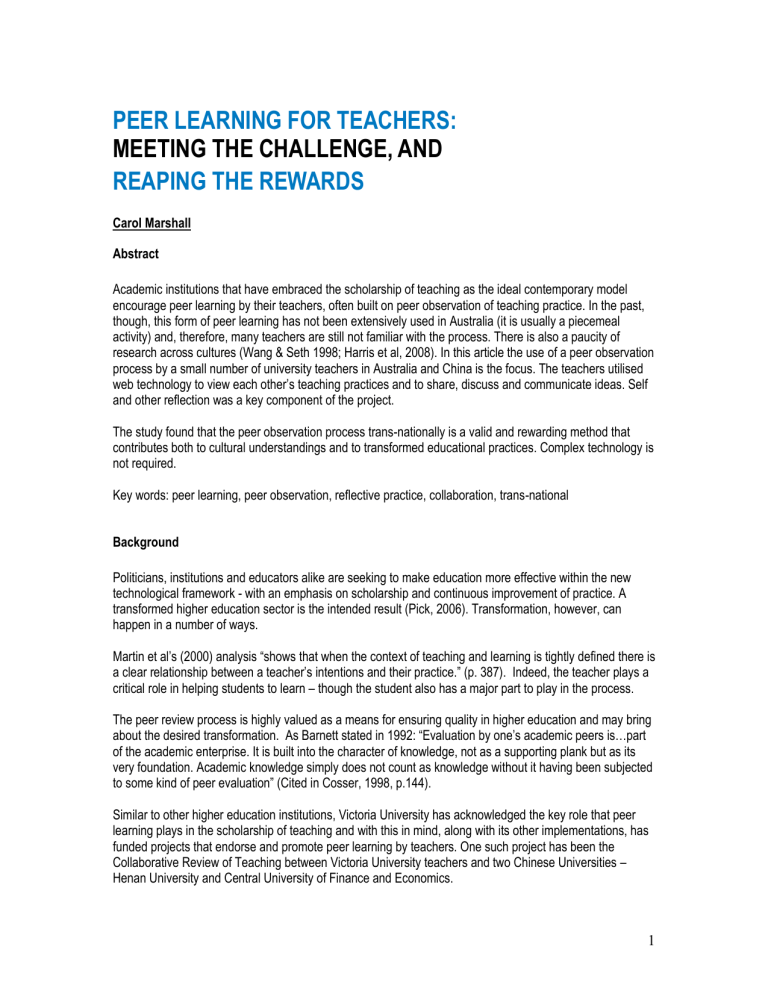

PEER LEARNING FOR TEACHERS:

MEETING THE CHALLENGE, AND

REAPING THE REWARDS

Carol Marshall

Abstract

Academic institutions that have embraced the scholarship of teaching as the ideal contemporary model encourage peer learning by their teachers, often built on peer observation of teaching practice. In the past, though, this form of peer learning has not been extensively used in Australia (it is usually a piecemeal activity) and, therefore, many teachers are still not familiar with the process. There is also a paucity of research across cultures (Wang & Seth 1998; Harris et al, 2008). In this article the use of a peer observation process by a small number of university teachers in Australia and China is the focus. The teachers utilised web technology to view each other’s teaching practices and to share, discuss and communicate ideas. Self and other reflection was a key component of the project.

The study found that the peer observation process trans-nationally is a valid and rewarding method that contributes both to cultural understandings and to transformed educational practices. Complex technology is not required.

Key words: peer learning, peer observation, reflective practice, collaboration, trans-national

Background

Politicians, institutions and educators alike are seeking to make education more effective within the new technological framework - with an emphasis on scholarship and continuous improvement of practice. A transformed higher education sector is the intended result (Pick, 2006). Transformation, however, can happen in a number of ways.

Martin et al’s (2000) analysis “shows that when the context of teaching and learning is tightly defined there is a clear relationship between a teacher’s intentions and their practice.” (p. 387). Indeed, the teacher plays a critical role in helping students to learn – though the student also has a major part to play in the process.

The peer review process is highly valued as a means for ensuring quality in higher education and may bring about the desired transformation. As Barnett stated in 1992: “Evaluation by one’s academic peers is…part of the academic enterprise. It is built into the character of knowledge, not as a supporting plank but as its very foundation. Academic knowledge simply does not count as knowledge without it having been subjected to some kind of peer evaluation” (Cited in Cosser, 1998, p.144).

Similar to other higher education institutions, Victoria University has acknowledged the key role that peer learning plays in the scholarship of teaching and with this in mind, along with its other implementations, has funded projects that endorse and promote peer learning by teachers. One such project has been the

Collaborative Review of Teaching between Victoria University teachers and two Chinese Universities –

Henan University and Central University of Finance and Economics.

1

This peer observation process (and the collaboration required) demands much from the teachers involved.

In this valuable endeavour teachers are required to open their teaching to the scrutiny of their peers. It requires two or more teachers, who trust each other’s judgments and who see the importance of reciprocity, to focus their time and energy on generating new educational meanings and evolving better meansfor supporting learning. Whilst the ideal scenario is colleagues meeting face to face, in this particular instance teachers who had never met learnt from each other’s philosophies and practices.

Aim of the Peer Review Project

Even though there is an extensive literature on peer review of teaching in universities and its implementation

(Gosling & D’Andrea, 2002) there appears to be only one report in a transnational setting (Wang & Seth,

1998). Furthermore, in this case the participants were not university teachers and it was not a reciprocal process. The aim of this current project was to extend knowledge and understanding of the peer review process cross-culturally. In so doing it was hoped that trust would evolve through relatedness, discoveries and understandings - and an authentic reflection on teaching practice would be stimulated. It was also anticipated that this would lead to improvements in teaching practice.

The process required teachers to collaborate by means of observation, enquiry and reflection to better understand their personal philosophies of education and their day-to-day practices, with the intention of improving student learning.“It is a means of making the focus and purpose of reflection more explicit and effective through allowing (teachers) to consider their roles as professional educators, and to seek and engage in relevant developmental processes as a consequence. In so doing, peer observation becomes key in attempting to define the quality of learning and teaching within an institution” (Hammersley et al 2005, p.213).

Method of Peer Review

There are a variety of approaches to peer review and two inter-related types: formative and summative. The process itself is an intentional act designed to both assess teaching performance (summative) and help teachers improve their practice (formative).Whilst the “Transnational Peer Review of Teaching” focused on the formative type it also included some summative aspects. Likewise, though there are numerous ways of engaging in peer review of teaching, this project concentrated on forming pairs of teachers for discussion, analysis and reflection.

The teachers involved were all ESL/EFL teachers and all were volunteers - drawn from individuals expressing interest or from following up on colleagues’ recommendations of peers as potential partners.

Freedom of choice in volunteering for this exercise was considered a necessary component as it would be more likely to provide enthusiastic, committed and engaged participants in the process.

The ‘word’ was circulated at workshops, meetings, through phone and email contact. The four teachers from Victoria University (two male, two female) who displayed interest were briefed at a meeting as to the purpose of the project and the process involved. Those who attended the meeting were already semicommitted and attended to access the finer details and procedures – plus gauge an estimate of the time commitment to fit in with their existing workloads.

2

These teachers were paired with three Chinese teachers from Henan University (all female) and one from

CUFE University (a male) who had previously displayed interest, been briefed via Skype and had committed to the project. Prime motivators for all the teachers were:

To participate as researchers

To explore different teaching approaches across cultures

To enhance cross-cultural education

Process of Choosing a Partner

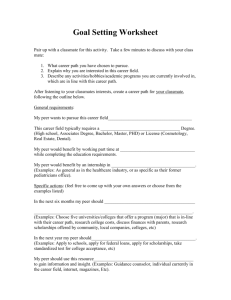

A blog was created and each teacher was requested to post a photo and a personal profile on this site (See

Appendix 1). The idea was that selecting a partner would be a less harrowing or difficult process and personalizing one’s profile with a photo would make it a friendlier, informal and more intimate process. Each teacher had access to authorship of the blog, too, so that anyone could write, comment on postings or even edit another’s work. The blog was restricted to the participants in order to provide a protected space for discussion related to the project.

It was found that after initial establishment of partnerships, email and Skype were the preferred means of communication. Skype provides free video and voice calls, instant messaging and the transfer of files. All that is required is access to a broadband Internet connection – a simple device that the participants had no obvious difficulty implementing.

Skype was decided on after another Internet communication tool - Elluminate – was trialled. Elluminate is another web-based technology that allows for real time collaboration, discussion and interaction. However it was decided that for this project a sophisticated technology with such assets as breakout rooms,

PowerPoint imports and cut/paste graphics was unnecessary for the purpose and would place additional loads on the teachers involved. Elluminate also proved less suitable to requirements due to ‘fade out’ and

‘voice volume’ difficulties, which were experienced in trials from Australia with participants in China.

Each teacher chose a partner based on the information posted to the blog and from follow-up Skype and/or email communications with their potential partner. It was left to participants to determine the amount of time allocated to their interactions and the preferred tools of communication. The process of establishing partnerships proved to be a smooth one. Though it was ‘first in, first served’ each teacher gravitated to a partner that was a suitable match and one they were happy with. Whilst partnerships were quickly established there were several minor hitches at the start. One male participant from Victoria University withdrew due to other work commitments. However, another person (female) volunteered the same day.

The other hitch was establishing regular contact with the partner both to establish trust and cement the partnership. As teachers had major teaching commitments that took priority it was up to the Project

Manager to keep the project at the forefront until the teachers involved had established communication

‘routines’ and project requirements within their pairs.

Commitment Required of each Partnership

Once teachers were informed of the project and partners established they were required to undertake the following:

Prepare a video of one of their teaching sessions and send it to their partner

Observe the teaching video their partner had sent them

3

Comment, discuss and evaluate their own teaching/ partner’s teaching based on the videos

Provide/receive feedback from their colleague on their teaching practices based on their videos and on interactions, exchange of ideas and on the personal requests of each partner

Identify and if possible provide evidence of knowledge growing or practice changing

If possible, write an article on their experience for the benefit of fellow teachers, higher education institutions and the educational community. The article was to be submitted to a peer reviewed journal.

Teachers were also asked to maintain a reflective journal on their experience. Advice regarding format and method was given. Any guidelines circulated were solely to clarify ideas and support and sustain participation. Pavlovich’s (2007) journal article on reflection was found to be especially helpful. Although the traditional journal method was recommended as the preferred means of recording, several teachers chose to use Skype contacts and discussions as their ‘journal entries’ – this was particularly in the case where

Skype was regularly utilised by the pair – or email records where this was the regular and predominant means of communication chosen. Several partners also adhered to a combination of the two communication tools. Thus data was collected through the blog, email, Skype and a video recording of the partner teacher’s lesson.

Peer Observation Method

Each teacher video-recorded a lesson with the help of camera-adept colleagues and the recording was couriered either by a staff member visiting the other country or by a commercial courier company. The teacher then viewed the video and gave feedback based on the requests of their partner as well as on other educational aspects. Feedback was predominantly provided via email and Skype. Interestingly enough, once personal profiles were pasted on the blog and partners selected, there was minimal blog activity as partners preferred to concentrate on their pair exchanges instead. Some valuable insights, however, were posted on the blog including the following snippets:“(Peer observation) is really useful in that we can learn a lot from the other teachers' delivery process, their teaching beliefs, teaching styles, teaching methods applied there, and teaching materials. But the problem is that sometimes not every teacher is ready to welcome peer observers, which will make him or her more nervous and unnatural. In addition, when we evaluate the teachers' teaching, we usually give them a higher score than it should be, worrying that lower scoring may affect their teaching reputation. There is another problem - some teachers are so busy that they

have no time to go to other teachers' classrooms” – (Chinese teacher, May 2009).

An Australian teacher responded with the following:

Whenever I have been involved in teacher observations I have made sure of the following:

• There is a clear statement about what constitutes acceptable performance.

• There are clear procedures for measuring this acceptability.

• That the ‘evaluator’ has enough experience and credibility to reliably measure the defined acceptability.

• That the following aspects of the observation are clearly defined: the purpose, the ‘audience/s’ of the evaluation, the ethical considerations, the mechanisms for reliable data collection, the means to validly interpret and analyse the data, the process of developing recommendations, the time allocated for the complete process and the reporting / feedback process.

Another teacher added:

I think that any evaluation / peer observation process should include these procedures:

• Informing the teacher prior to any evaluation or observation of the purposes of the evaluation, when it is to occur and how it is to be done

4

• Reliably observing the teacher using agreed observational mechanisms

• Immediately after the observation, discussing the observation with the teacher and making recommendations

• Following up to see if the recommendations are appropriate and are being followed.

Similarly these astute comments on ESL as distinct from EFL teaching were posted:

The ESL/EFL distinctions as I see them relate mainly to the following: the purposes of learning, the purposes for learning and the issues around communicative language teaching in EFL contexts… a. The purposes of learning: The specific language policy of the relevant government / ministry affects what is taught, how it is taught (e.g. the acceptable methods of teaching, and therefore learning, and the amount of total curriculum time devoted to English language teaching), how it is assessed, and the use of the results of such assessments e.g. governments generally see ESL as a social necessity whereas governments may see EFL as a means of economic development. This affects the aspects of needs based learning and negotiating the learning curriculum. They are often not possible in EFL contexts. b. The purposes for learning: This concerns how English language learning is viewed culturally, how it is viewed by the students, and the expectations of such language learning e.g. EFL is often seen as an academic discipline to achieve university entrance, or a better chance at being accepted for migration to an

English speaking country or a chance to improve one’s economic lot in life. However, ESL is seen as a necessary means of communication and social access. The motivation for learning is different, and far more specific in EFL contexts. The intrinsic, integrative motivation of the ESL learner may be replaced by the extrinsic, instrumental motivation of the EFL learner. In contrast, some EFL learners may view learning

English as an academic discipline not a 'living' language, an academic subject that is not as valid, nor as important for access to future positions of power as say mathematics, science, or technology studies. These aspects also affect needs based learning, the types and levels of stress in EFL classes, opportunities for acquisition of the language and the negotiation of the learning curriculum. Again, these may not be possible in EFL contexts. c. The role of Communicative Language Teaching in the EFL context: It is far more difficult to develop meaningful communicative exercises in the EFL context compared to the ESL context. The latent knowledge of the students concerning language learning is not as readily available or accessible to EFL teachers and learners. There is no or very limited external back up, chances to practice, or incidental learning opportunities in the EFL context. Added to these problems, there is the need for teachers to be creative and confident enough to develop their own communicative activities based on their own knowledge of the

students’ language learning needs, all despite the problems noted above.– an Australian teacher, June

2009.

Findings

Once teachers are clear of requirements and procedures their enrolment in the process is assured. However it requires intensive encouragement, communication and networking to establish the initial partnerships. It is certainly worth spending the time initially to harness the volunteers and build the partnerships. This ensures that once these requirements are established the process flows reasonably smoothly.

Locating IT tools that served the purpose for communication purposes took time and effort too. Elluminate was trialled and proved unsatisfactory – mainly in terms of maintaining communication with participants in

China. Simple tools and procedures worked best. The blog, Skype and email were adequate for the purpose and most reliably guaranteed results – especially as the tasks were not complex and a high level of

5

technological ‘know how’ was not required. The purpose, overall, was to review teaching and not one’s IT wizardry!

A growing body of evidence suggests that ‘when teachers collaborate … knowledge grows and their practice changes’ (David 2008: 87). However, whilst collaboration is a promising strategy for strengthening teaching and learning, it may also be one of the most difficult to implement. Not only does it take time and effort but also for some teachers it can feel quite daunting – even threatening. In the current context it was found that teachers in both China and Australia adapted readily and openly to this project. This is interpreted as due to the professionalism and experience of the teachers taking part and to the solid foundation on which it was established.

Fundamentally, teacher participants gained insights into the differing methodologies, ideology and cultural contexts, and their cross-cultural understandings of teaching and learning improved as a result. They also declared that the reflective journal definitely assisted this process.

Specifically, in response to the question: “What did you learn from participation in this project?” the participants posted the following:

How to organize a project, distribute tasks and write reflective journals

How to improve academic writing ability

How to research transnationally

The differences in teaching and learning approaches and other cultural factors which shape teaching modes – particularly the Chinese formal, teacher dependent method versus the more flexible, informal Australian approach where students have greater autonomy

The interactive style in Australia, based ongroup discussions, is made (in part) possible by the round table seating arrangements in the classroom – rather than the row on row traditional arrangement in China

One Australian teacher articulated that he needed to be more aware of project demands, stages, timelines and requirements before taking on a project – given his current workload. He also emphasised the need to sensitively understand each other’s contexts and backgrounds and that effective cross-cultural teacher- evaluation feedback is fraught with ethical, professional and personal concerns related to the disembodied nature of the communication and the fragility of the developing relationship.

The other key question: “How did this change your teaching practice?” elicited the following responses:

Integrating the other culture’s methodologies that had been previously overlooked in teaching practice

Altering existing patterns of thinking surrounding classroom activities and organization

Allowing for more student autonomy and responsibility and further encouraging them to focus on the process of learning and exploration

One teacher now views face-to-face evaluation as more effective than on-line due to subjective concerns.

In summary, as a Chinese teacher expressed it, The mission of a university is teaching and research. Only through research – especially through collaborative research which could enhance mutual understanding – can teaching make great strides within joint programs.

6

Discussion

Whilst this was a small project with only eight participants it is seen as significant in its focus and its implications for future practice in this area.

Collaboration amongst colleagues is imperative for progress – not least in educational institutions.

Furthermore, peer observation in the transnational realm is potentially very valuable for furthering trust and understanding and the sharing of mutually beneficial ideas for student, teacher, manager or industry. The scholarship of teaching and learning will be enhanced in the process. Miscommunication due to distance and technology was not a serious issue. Whilst caution is required in reading too much significance into this small study, it did result in a number of positive outcomes. The success of this study suggests that a more extensive project on collaborative peer observation of teaching should be conducted.

Recommendations

Peer learning can lead to greater respect and deeper relationships between colleagues. Therefore it is recommended as an activity which should be encouraged especially between transnational colleagues.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support provided by the eight teachers involved (Laura, Lucia, Beth, Jack, Rob,

Martyn, Raquel and Lynne) in China and Australia.

Editorial assistance has been thoughtfully provided by Roger Gabb and Fiona Henderson. Any editing of participants’ material has been of a minor nature and made solely for the purposes of clarifying meaning.

7

References:

Cosser, M. (1998). Towards the design of a system of peer review of teaching for the advancement of the individual within the university, Higher Education, Vol. 35 (2), 143-162.

David, J. L. (2008). Collaborative Inquiry, Educational Leadership, Vol. 66 (4), 87-88.

Gosling, D., & D’Andrea, V., (2002). Peer observation of teaching, a select annotated guide to publications and websites. Higher Education Academy Resources, U.K. 1-6

Would you view collaboration as being, necessarily, at the forefront of educational undertakings in the future?

Cited on 20/4/09 http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resources.asp?process=full_record§ion=generic&id=183

Hammersley – Fletcher, L., & Orsmond, P. (2005) Reflecting on reflective practices within peer observation.

Studies in Higher Education, Vol. 30 (2), 213 – 224.

Harris, K-L., Farrell, K., Bell, M., Devlin, M., James, R. (2008) Peer review of teaching in Australian higher education, 1 – 115. Cited on 23/3/09 http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au/pdfs/PeerReviewHandbook_eVersion.pdf

Martin, E., Prosser, M.; Trigwell, K.; Ramsden, P.; Benjamin, J. (2000). What university teachers teach and how they teach it, Instructional Science, Vol. 28, (5-6) 387 – 412.

Pavlovich, K., (2007) The development of reflective practice through student journals, Higher Education

Research & Development, Vol. 26, (3) 281 – 295.

Pick, D.; (2006). The reframing of higher education, Higher Education Quarterly, Vol. 60 (3) 229 – 241.

Wang, Q., & Seth, N. (1998). Self-development through classroom observation: changing perceptions in

China. ELT Journal, Vol. 52 (3) 205 –213.

8

Appendix 1

China Peer Review: Guidelines for the Personal Profile

The following are guidelines as to what you could state in a personal profile to help other participants choose a partner:

Provide a photo - this gives a personal and friendly touch to your communications

State your academic qualifications - university degree, postgraduate etc.

List any other relevant qualifications

Give a history of your employment in education – roles and responsibilities

Mention other work related experiences that have contributed to your education career

Provide a record of any publications written or presentations you have made

State your special interests in education

List your hobbies and/or other areas of special interests

Other: whatever you’d like to say to assist another participant in knowing who you are

9