Human Impacts Case Studies - jonesyatnorwood

advertisement

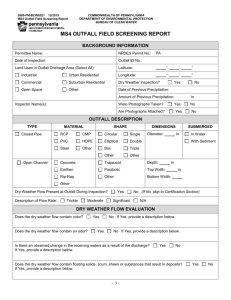

Investigating the impact of human activity on the coast Coasts are constantly changing, dynamic environments. They undergo spatial change over time on a daily, seasonally, yearly and geologically spaced time scale. They are considered a natural environment. However, the ever increasing presence of human activity is changing their composition. The coastline of Victoria is home to approximately 85 per cent of the state’s population. The distribution of urban centres in the state is likely to intensify. This means that human interaction with and influence over the coastal environment is only going to increase. Your task is to study the impact that human activity is having on the Victorian coastline. And identify changes that are occurring due to human interaction with the natural environment. In order to complete your task, you will need to study ‘New Perspectives’ pages 87 to 91. This chapter covers various aspects to coastal change, including water quality, habitat loss, coastal development, sediment movement and beach safety, as well as current and future management of the local coastline. You will also be required to investigate two case studies, exemplifying the impacts of human activity on the coast. Case study 1 (Gunnamatta outfall) is included in this document. Case study 2 (Dredging the Bay) is accessible by logging on to the website below and navigating your way to the bottom of the ‘VCE Geography’ page. Here you will find a link to Dredging the Bay. Case Study 2 details found at: http://jonesyatnorwood.wikispaces.com Task Carefully read and investigate both case study examples. Take notes in your folder to be used for final SAC revision on Changes to the Coastal Environment. Complete the research questions including in this document. Case Study 1: Gunnamatta Water Pollution Article 1 ‘A beach where the waves are truly sick’ PHIL TRIGGER is a Mornington Peninsula legend who has surfed the waves at Portsea, Flinders, St Andrews and Gunnamatta for 40 years. His five-shop surf gear business, Trigger Brothers, began at Chelsea in 1970. At 55, he retains his original passion for surfing and still competes. But Mr Trigger is concerned that people are getting sick after surfing at Gunnamatta, where 430 million litres of partly treated sewage a day from Melbourne is discharged 25 metres off shore, a volume equivalent to filling the MCG to the grandstands. "One day around Christmas you could smell it from the car park, and the water was brown and there was froth on the beach," he said. Lachy McDonald, 19, grew up in Torquay, on the Surf Coast, surfing without health incident. Since moving to the Mornington Peninsula and surfing at Gunnamatta, he has suffered many ear infections. "It's a problem for a lot of surfers," he said. "A lot of them are wary of surfing at Gunnamatta." Some illnesses surfers have complained of include gastric, ear, respiratory, skin and eye infections and, in six cases, viral meningitis. Simon Forward surfed at Gunnamatta four or five times a week before contracting viral meningitis five years ago. "I lay in a dark room for 10 days," he said. While impossible to trace the illness to the treated effluent, Mr Forward's doctor said the water at Gunnamatta was "a pretty good option". Mr Trigger is often cut while surfing but when his surfboard fin nicked him recently at Gunnamatta the sore became infected and "lumped up". "It's incredibly disappointing," Mr Trigger said of the effluent outfall. "It compromises so much of that stretch of coastline. Who cares how much money it costs to fix it? Maybe we could pay for it with a state levy." Melbourne Water operates the treatment plant at Carrum that discharges at Gunnamatta. The waste is treated to "class C" level. The Clean Ocean Foundation, a local environment action group, claims this does not remove all harmful viruses. It wants the waste treated to "class A" level, making it suitable for recycling, and protecting beach users. What is pouring into the ocean is made up of freshwater containing pathogens, including viruses and bacteria, chemicals, residual chlorine and heavy metals. The Clean Ocean Foundation strongly recommends not swimming between Gunnamatta and Rye. It says the beaches are often unsafe for surfers and swimmers, but the Health Department issues no warnings. Melbourne Water tested the water at Gunnamatta and nearby St Andrews beach on June 9. The results showed enterococci (the prime indicator of the health of recreational marine waters) 45 times the EPA's acceptable level. The results were not a one-off. Eighteen of the 85 testing dates since 2000 delivered results exceeding EPA criteria. The foundation did chemical and biological tests on March 8, sampling in a pollution slick, called a diatom bloom, at Rye beach. Despite EPA denials that there was a link between the blooms and the Gunnamatta outfall three kilometres away, the tests confirmed the blooms were a result of sewage. The tests also revealed toxic ammonia concentrations five times the EPA's recommended level. "The presence of ammonia and bacteria at these levels can only be attributed to the sewage discharge from the Gunnamatta outfall," Mark Aketer, an environmental scientist with the foundation, said. The Government announced in September 2004 a study into the feasibility of an effluent pipeline to Gippsland to reduce by 80 per cent the outflow at Gunnamatta. The proposal involves a water reclamation plant that would treat water from the Latrobe Valley sewerage system and the Carrum plant for use in industry. The price tag is about $1 billion. But critics say progress is too slow. "We call on the State Government to stop playing politics with our environment and deliver on the promises to upgrade the treatment plant," the foundation's president, Pete Smith, said. Mr Aketer said: "If dumping nearly half of Melbourne's sewage and industrial wastewater onto the beach at Gunnamatta is not a health issue for the 350,000 visitors to Gunnamatta Beach each year, then what is?" Melbourne Water's June tests showed swimmers had a greater than one-in-three chance of contracting illness in the surf zone. Mr Aketer said it was outrageous the EPA knew the results were unacceptable, but still allowed Melbourne Water to delay its Carrum upgrade. Melbourne Water spokesman Ben Pratt said that during the recent algal bloom, enterococci and E.coli levels were within EPA licence limits and those considered safe for recreation. Acting EPA chairman Bruce Dawson wrote to The Mornington Peninsula Leader last week saying EPA data showed enterococci levels during the bloom were within safe levels. "EPA has reviewed Melbourne Water's compliance with its licence during this time and has found that the outfall at Gunnamatta has operated within its required licence limits," he said. "There is no evidence to suggest raw sewage has been discharged from the outfall." Mr Dawson told The Sunday Age the EPA had given Melbourne Water approval in 2002 to upgrade the Carrum treatment plant to a class A discharge. As part of this, the EPA required the existing pipe to be extended two kilometres to reduce the discharge's impact on the environment. Melbourne Water then sought and was given a time extension to enable the Government's feasibility study to be completed. Environment Minister John Thwaites said the feasibility study was not scheduled to report until September, and decisions on the Carrum upgrade and the Gippsland proposal could not be taken in isolation. "It is a major undertaking to determine what path to take, and we're on track," he said. Mr Thwaites said $85 million had been spent on the Carrum plant and further upgrades towards a class A discharge were planned. GUNNAMATTA beach is known for its unpredictable and often dangerous swells. It is one of the great challenging surfing spots in Victoria. In his guide Surfing Victoria, Richard Loveridge says Gunnamatta is "generally considered the premier spot for beach breaks on the Mornington Peninsula" with "consistently good waves all-year-round". But he also writes: "It is bitterly disappointing that surfing at Gunnamatta has been compromised by the sewerage outflow from Boags Rocks. The water is permanently dirty with a detergent-like odour. Complaints of head colds, earaches and nausea are now commonplace." Article by Peter Wilmoth, Posted on April 2, 2006 Article taken from: http://www.theage.com.au/news/national/a-beach-where-the-waves-are-trulysick/2006/04/01/1143441378836.html Retrieved on 26th Feb 2010. Article 2 ‘Time to close the Gunnamatta ocean outfall’ On Sunday 15 March, I attended the Clean Ocean Foundation rally at Gunnamatta. The Greens support the closure of ocean outfalls all over Australia. While 350 million litres of partially treated sewage is pumped into the ocean at Gunnamatta every day, only about 60 kilometres south-east of the outfall, the state government plans to build a monstrous, energy guzzling desalination factory that will pump water from the ocean, use huge amounts of energy and chemicals to remove salt to ‘create’ fresh water and then pump the waste from this process back into the ocean. How crazy is that? Instead of forging ahead with the expensive, unnecessary, carbon polluting desalination, the government should close the Gunnamatta outfall,recycle the treated sewage and step up other domestic, industrial and agricultural water conservation and recycling activities. Expert advice provided to the government in 2007 recommended a focus on programs to reduce water use in homes and businesses instead of building the north-south pipeline or the desalination plant. It's a pity that time and the opportunity to install many more water tanks in homes and businesses have been wasted as we start to see some rain falling. This would have created local employment, made a significant contribution to water savings and be less costly than desal. By Amanda Sharp - Posted on 15 April 2009 Article taken from: http://mps.vic.greens.org.au/node/1077. Retreived on 26th Feb 2010. Research Questions Case Study 1 - Gunnamatta 1. Identify the impact of human activity on the coastal environment ooutlined in case study 1. (Include an accurate map to locate the problem, find photographic evidence of the issue and provide a detailed description of the problem). 2. At what rate and scale is this issue occurring? 3. Who is affected by the issue and to what degree of importance are the resources under threat in this case study? Give examples. 4. What is the public response to the issue identified in case study? Do you agree with public statements made? Why, or why not? 5. Describe the links and relationships (spatial interaction) that exist between the natural environment and human activities along the Gunnamatta coastline. 6. How is this issue being managed or controlled at present? 7. Give suggestions of ways to better manage this problem in the future. 8. With reference to Cape Schanck and Gunnamatta, explain both the positive and negative impacts that human activities can have on a coastal environment. Case Study 2 – Dredging the bay 1. Identify the impact of human activity on the coastal environment ooutlined in case study 1. (Include an accurate map to locate the problem, find photographic evidence of the issue and provide a detailed description of the problem). 2. Describe the links and relationships (spatial interaction) that exist between the dredging of the bay and the natural environment 3. With reference to the ‘Dredging the bay’ Case Study, explain both the positive and negative impacts that human activities can have on a coastal environment. 4. At what rate and scale is this issue occurring? 5. Who is affected by the issue and to what degree of importance are the resources under threat in this case study? Give examples. 6. What is the public response to the issue identified in case study? Do you agree with public statements made? Why, or why not? 7. How is this issue being managed or controlled at present? 8. Give suggestions of ways to better manage this problem in the future.