Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult

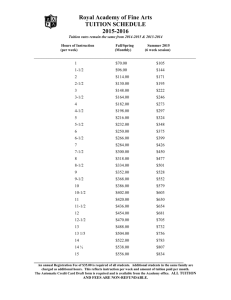

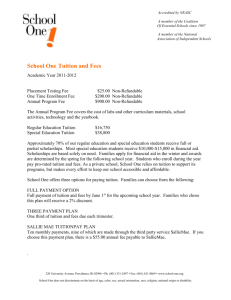

advertisement

CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) May 2012 Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies INTRODUCTION At no time in recent history has the importance of adult education been greater and the funding more threatened.1 Despite the fact that at least 93 million adults in the U.S. could benefit from basic skills education to improve their economic success and mobility, funding for these services is stagnating at the federal level and being slashed in statehouses and state agencies across the country. Yet demand for these services remains high, with at least 160,000 people on waiting lists that exist in nearly every state.2 Not only is demand for these services strong, but students with low basic skills now need more education than ever to compete for jobs in a slowly recovering economy. The jobs that disappeared in the last recession are being replaced with jobs that require higher levels of education and, often, a postsecondary credential. In fact, one estimate suggests that 64 percent of jobs by 2018 will require some level of postsecondary education. To meet this demand for educated workers, some states are adopting innovative instructional strategies that combine basic skills education with postsecondary-level coursework or job training.3 These approaches, called “career pathways” or “bridge programs,” are cropping up across the country and being encouraged and supported by the U.S. Departments of Education and Labor in recent competitive grant programs, yet they can be more costly than traditional models of adult literacy and education. Yet, already a persistently underfunded system, adult education has reached its capacity, and can no longer simply “do more” with less funding every year. These new needs for the adult education system amid declining revenues begs the question: How can the system continue to improve instruction, meeting higher-level demands for students, with fewer and fewer resources each year? Traditionally offered for free or at a low cost, some states have adopted new tuition policies for adult education services, yet getting mixed results. Additionally, changing standards and a new cost structure for the GED are putting even more pressure on an already strained system. To begin the conversation about new funding structures and new opportunities for funding, CLASP and NCSDAE initiated a national survey of statewide tuition and financing policies. The survey covered a range of issues, including: The division of funding by local, state, federal and tuition sources; 1 Adult education includes adult basic education for those at the lowest skill levels, adult secondary education and GED preparation for those at higher skill levels, and English language services. It primarily serves those without high school diplomas, high school graduates who are not college-ready, and students with limited English language proficiency. Services are supported by federal funding under Title II of the Workforce Investment Act (Adult Education and Family Literacy Act), as well as state and local funding. A variety of local providers offer adult education, including K-12 districts, community colleges, and community-based organizations. 2 NCSDAE, Adult Student Waiting List Survey, 2009-2010, http://www.ncsdae.org/2010%20Adult%20Education%20Waiting%20List%20Report.pdf 3 NAEPDC, Adult Education Supporting the President’s Workforce and American Graduation Initiatives, 2010, http://www.naepdc.org/State%20Alignment%20Initiatives%20-%20FINAL%202.2.10.pdf 1 Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 How the agencies that administer adult education determine the funding allocations to local programs; The existence of any special discretionary resources available to incent local innovation; The existence of statewide tuition/fee policies and the amount of such tuition/fees; The current cost to students to take the General Educational Development (GED®); and Any expected changes in state policy to make the GED® more affordable to students when a new, computer-based assessment is introduced in 2014 by the GED Testing Service. State responses to these questions are included in this report, which is intended to shed light on important policies that govern the way adult education is funded, including those costs borne by local districts and institutions, states, the federal government, and students. It does not represent a causal analysis of why certain states choose one method over another or what causes a particular outcome. In other words, through this report, we hope to supply information about the variety of ways that adult education is funded, not provide an analysis of which policies yield the greatest revenue. Methodology This survey was administered in February 2012 through an online survey instrument. It was distributed to State Directors of Adult Education in all 50 states plus the District of Columbia. CLASP followed up with some respondents to clarify answers and, in some cases, to obtain detailed information on a particular topic. CLASP also conducted additional research beyond what was reported by states. Limitations While every attempt was made to ensure the data presented are accurate and comprehensive, there are some limitations to the survey findings presented in this report. Primarily, while the survey responses reflect the vast majority of states, seven states and the District of Columbia did not respond to the online survey. In addition, not all of the states that responded answered all of the questions completely. The diversity of funding policies and governance structures in adult education across states is also a challenge. While federal funds are provided to each state and the District of Columbia, most programs receive a mix of federal, state, local, and sometimes philanthropic funding. In some cases, the state agency does not collect complete information on the myriad funding sources, and thus, is not able to report on the breadth or depth of funding that exists. States also vary widely in terms of governance, state law, and policy—making them nearly impossible to compare uniformly. 2 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 CHARACTERISTICS OF PARTICIPATING STATES Forty-three states submitted responses to the online survey. These states represent diversity across several dimensions: administering agency, geography, number of students enrolled in adult education, and percentage of students in ABE, ASE, and ESL. Governance The agency that administers adult education varies by state and can play an important role in determining the overall direction and goals of the program. Of the 43 states that responded to the survey, six administer adult education through the workforce system (such as the Department of Labor or the Department of Workforce Development), twelve run it through the postsecondary system (such as the State Board for Community and Technical Colleges or the Board of Regents), and twenty-five states administer the program in the Education/K-12 system (such as the Department of Education). In limited cases, agencies span more than one of these systems. Table 1. Administering Agencies of Adult Education in Survey States States Administering Agency Labor/Workforce System (AR, IN, MD, MI, SD, TN) Postsecondary/Community College System (AL, GA, IL, KS, KY, LA, MS, NC, OH, WA, WI, WY) Education/K-12 System (AZ, CA, CO, CT, DE, HI, ID, IA, MA, MN, MO, MT, NE, NV, NH, NY, ND, OK, PA, RI, SC, TX, UT, VT, VA) 6 12 25 Geographic Diversity The states also have significant geographic diversity, with all of the major Census regions represented. Twelve states are in the West; 10 states are located in the Midwest; 8 states are located in the Northeast; and 13 states are in the South. Table 2. Survey States by Region States 12 10 8 13 3 Region West (AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NV, ND, SD, UT, WA, WY) Midwest (IL, IN, IA, KS, MI, MN, MO, NE, OH, WI) Northeast (CT, DE, MA, NH, NY, PA, RI, VT) South (AL, AR, GA, KY, LA, MD, MS, NC, OK, SC, TN, TX, VA) CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 Size of the Adult Education Program States vary widely in the number of adult education students they serve—this largely represents the significant differences in population, but can also reflect differing socioeconomic trends, as well as the level of immigration in a state. States in this survey are representative across the spectrum of how many students are served in adult education. The state that serves the most students is California, which enrolled 392, 918 students according to 2010 data from the National Reporting System (NRS).4 The survey state with the fewest enrollees is North Dakota, which enrolled 1,581 students. Other large adult education states include New York (122,833 students) and North Carolina (115,312). Other small adult education states include South Dakota (2,423 students) and Vermont (1,590 students).5 Proportion of Students in ABE vs. ESL Individuals in adult education are included in one of three broad program types: Adult Basic Education (ABE), which serves students at the very lowest skill levels, typically 8th grade level and below; Adult Secondary Education (ASE), which serves students with intermediate and high-basic skills, typically 9th grade – 12th grade level; and English as a Second Language (ESL), which includes students with limited English skills at all levels. Among the survey states, 46 percent of students are in ABE, 12 percent of students are in ASE, and 42 percent are in ESL. This division between the three program types is exactly the Figure 1. Percentage of Adult Education Funding by Revenue same as the division at the national level, so the survey states Source reflect the national trend. States that report serving a high proportion of ESL students include Nevada (77 percent), California (66 percent), and Colorado (61 percent). States that report serving a low proportion of ESL students include Louisiana (6 percent), Montana (6 percent), and Mississippi (1 percent).6 HOW ADULT EDUCATION IS FUNDED Tuition 1% Local 9% Federal 45% State 45% States use a combination of federal, state, local, and tuition dollars to fund adult education services statewide, using a network of local providers. Federal funding from the Adult Education and Family Literacy Act (Title II of the Workforce Investment Act, or AEFLA) provides an annual stream of federal funding that is distributed to 4 The National Reporting System (NRS) is the performance accountability system that governs the use of federal adult education funding under Title II of the Workforce Investment Act. 5 These figures may not include all of the students that are served by adult education services in the state. States may use local or state funding to serve students and not include these students in the National Reporting System. In addition, to be counted in these totals, students must be enrolled for at least 12 hours. 6 These figures may not include all of the students that are served by adult education services in the state. States may use local or state funding to serve students and not include these students in the National Reporting System. In addition, to be counted in these totals, students must be enrolled for at least 12 hours. 4 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 states via formula. States and local districts or institutions also contribute funding for adult education, though the division of revenue by source varies wildly by state. In order to receive federal adult education funding, states must match the federal contribution with at least 25 percent in nonfederal funds (which includes state and local funding). These funds may be provided in cash or in-kind. Historically, most states have contributed funds well beyond this match level with funding from the state, local institutions or school districts, or tuition. In this survey, states reported that, on average, 9 percent of their funding comes from local sources, 45 percent comes from state sources, 45 percent comes from federal sources, and 1 percent comes from tuition charged to students (see Figure 1).7 Federal Funding Federal funding from Title II of the Workforce Investment Act comprises, on average, 45 percent of the total funding for adult education in the survey states. The amount of WIA Title II funding has generally remained flat in the last several years, but has dropped by 17 percent in real dollars since the height of funding in 2002. In FY2012, just under $600 million was appropriated for WIA Title II.8 State Funding Among the survey states, three contribute no state funding for adult education, nine contribute 25 percent or less in state funds toward total adult education funding, thirteen contribute between 26 percent and 50 percent, twelve contribute between 51 percent and 75 percent, and five contribute 76 percent or more in state funding (see Table 3). Table 3. Percentage of Total Adult Education Funding from State Funding by State States 3 9 13 12 5 7 8 Percentage of State Funding Contribution Contribute no state funding (AZ, CO, IA) Contribute 25 percent or less in state funding (KS, MT, NE, OK, SD, TN, TX, VA, WI) Contribute 26-50 percent in state funding (AL, CT, DE, GA, ID, IN, LA, MD, MS, MO, NH, OH, PA) Contribute 51-75 percent in state funding (HI, IL, KY, MA, MI, NV, NY, ND, RI, UT, WA, WY) Contribute 76 percent and over in state funding (AR, CA, MN, NC, VT) South Carolina was not able to provide this information. http://www.clasp.org/admin/site/publications/files/adult-ed-funding-enrollment-February-2012.pdf 5 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 Local Funding Among all states in the survey, local funding averages 9 percent, but this varies widely (see Figure 2). Twenty-five states report that no funding is contributed by local sources, which includes programs, school districts, and institutions. Of the remaining 17 states, 9 indicated the local contribution was 20 percent or more and 8 indicated that it was less than 20 percent (see Figure 2). The states with the highest local contribution were Connecticut (44 percent), Wisconsin (43 percent), and Colorado (40 percent).9 Connecticut Wisconsin Colorado Montana Kansas Maryland Nebraska New Hampshire Massachussetts Virginia Pennsylvania Ohio Indiana Tennessee Rhode Island Georgia Nevada 4 0 5 15 15 15 11 10 10 7 10 20 15 20 23 26 25 25 28 30 40 36 35 40 44 43 45 50 Figure 2. Percentage of Adult Education Funding from Local Districts, Institutions, or Programs in States that Report Local Funding Student Tuition and/or Fees Only five states reported that tuition is part of the adult education funding mix, resulting in an overall average of 1 percent for the percentage of funding that comes from student tuition and/or fees. Of these states, four indicated that this comprises less than 10 percent of their total funding for adult education and one indicated that it comprises 26 percent of its funding. A more detailed discussion of tuition and fee policies in the states can be found later in this report on page 13. Commentary Funding for adult education is a hot topic this year as many states are finding the level of state investment drastically declining as a result of multiple years of state revenue crises and budget shortfalls. And while this survey is not a definitive source of current state funding levels, state responses to this question seem to reflect a 9 For many years, states and localities contributed roughly $3.50 for every $1.00 in federal funding. This is no longer the reality; in fact, the results of this survey suggest that nonfederal contributions are closer to $1.20 for every $1.00 in federal funding. Colorado provides no state funding for adult education. 6 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 general disinvestment in adult education at the state level. In 2009, the Office of Vocational and Adult Education of the U.S. Department of Education reported that states and localities contributed roughly $3.50 for every $1.00 in federal funding. This is no longer the reality; the results of this survey suggest that nonfederal contributions are closer to $1.20 for every $1.00 in federal funding. Recent reports beyond the scope of this survey have also shown a growing trend among states and local districts to cut funding for adult education and English language services.10 State Profiles: MN, RI, WI Key Questions for Further Research Should the federal government contribute a greater share of the funding needed to educate low-skilled adults given the decline in state and local funding and the growing demand for these services? Forty-six percent of current adult students are non-English speakers and seeking to better integrate into society and jobs. As immigration is a national issue, should the federal government increase funding to address their language and citizenship needs? What are the key reasons why some states and localities contribute a much greater share of adult education funding than others? How does a larger state and local stake in adult education impact student outcomes? How does more or less reliance on federal funding vs. state and local funding impact student outcomes? How much of state funding is cash vs. in-kind? HOW LOCAL ADULT EDUCATION PROVIDERS ARE FUNDED Adult education services are provided through a network of providers that include, but are not limited to, local school districts, community and technical colleges, and community-based organizations. In order to determine the providers, states solicit multi-year plans from local applicants. To those successful applicants, states must distribute annually 82.5 percent of their federal allocation of AEFLA funds to those local programs and may also provide additional state funding. Recipients of these funds, in turn, serve students directly by providing an array of adult education, literacy, English language, family literacy, workplace education, career pathway and other services based on the needs of the locality. See Foster, Marcie. “With Budgets Slashed, Adult Education Programs Struggle to Keep the Lights On,” CLASP, February 21, 2012. 10 7 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies Federal Adult Education and Family Literacy Act Funding Competitive Grants to Local Providers for Adult Education Services Must use direct and equitable process for RFP. State must contribute 25 percent nonfederal match, to be used in the same way as federal funding. State Leadership Funding and Other Set-Asides 2012 State Adult Education Funding Must follow state requirements, which may be different than federal. Any portion used toward 25 percent match must be used in the same way as federal funding. Unlike other federal programs, such as WIA Title I Adult Programs and Youth Programs, state agencies—rather than localities—have significant influence on the types of activities and programs they wish to support. While programs must generally meet minimum requirements, such as the ability to collect and report data to the National Reporting System (the federal performance accountability system for adult education) the state is given some flexibility on the priorities on which they decide to distribute funds to programs. In soliciting multi-year applications, states must use a competitive grant process that provides for “direct and equitable access” to all eligible applicants. The intent of this provision is to ensure that the full range of adult education and English language service providers—including K-12 districts, community colleges, community-based organizations and others—are able to compete equally for federal funds. Due to the uncertainty of both federal and state funds, states allocate funds annually to the approved programs. How States Distribute Federal Funding Provided Under WIA Title II States provided a wide range of answers when asked how they distribute federal funding to local programs. Twenty-seven states say that the amount of funding provided to locals is determined by a formula that takes into account a combination of enrollment data, eligible population, and past performance. Seven states indicate that their funding is determined by a formula that takes into account only one of the above factors. Furthermore, nine states report that they do not use either of the above methods to determine the amount of funding that flows to local providers. Of these nine states that use an alternative method, the majority use some type of performancebased funding system for at least some portion of these funds. One state in this category awards funding according to a complex rubric that includes 10 dimensions of program operation and performance and weighs each of the factors differently. Some states report using a two-tiered approach to funding local providers. To ensure equity, funding is provided by formula (based on the number of adults without a high school diploma) to counties, which then grant the funds based on a competitive process. This ensures that services are provided with geographic equity but also maintains compliance with the federal “direct and equitable” provisions. 8 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 The use of performance funding to distribute federal funds to local providers is extensive, although states vary in terms of the student outcomes that they use as performance criteria. Not all states provided information on the measures they use, however, the most common performance indicators states report using to fund programs are: Educational functioning level gains,11 Number of GED’s/Adult High School Diplomas awarded, and Number of contact hours. Table 4. Division of States by Distribution Method of Adult Education Federal Funding States 27 How States Distribute Federal Funding to Local Adult Education Providers Funding to locals is determined by a formula that takes into account a combination of enrollments, eligible population, and past performance. (AL*, AR*, DE*, GA*, ID, IL*, IN*, IA, LA, MD*, MA*, MI, MS*, MO*, MT*, NE*, NV, NH*, NC, ND, OK, PA*, SD*, TN*, TX*, WA, WY*) 7 Funding to locals is determined by a formula that takes into account only one of the following: enrollments, eligible population, and past performance. (CA, HI*, KY*, OH*, SC, VT, VA) 9 None of the above is used to determine the amount of funding that flows to local providers. (AZ, CO, CT, KS, MN, NY, RI*, UT, WI) * Indicates the state also uses this method to distribute state funding. As previously mentioned, states often contribute additional state funding to adult education beyond the federal contribution (see page 5). Although states are not required by federal law to distribute this additional state funding beyond the required match in the same way as federal funding, twenty-two of the states indicate that they do use the same method (see Table 4). How States Distribute State Funding States that provide funding beyond the level of the federal 25 percent match can use their additional state funding differently than their federal funding. This is an important distinction as this funding can typically be used flexibly, depending on the state’s priorities and needs. Eighteen states report that they use or distribute state funding differently than federal funds. Of these states, eight report that state funding is distributed based on a formula that takes into account a combination of enrollments, eligible population, and past performance. Four states indicate that state funding is determined by only one of the above factors. Six states report that they do not use either of these methods to determine state funding distributions to local providers.12 11 In some cases, not all educational functioning levels are treated similarly. At least one state awarded double performance points for programs that helped students at the lowest basic skill levels move to a higher educational functioning level. 12 Three states (AZ, CO, IA) do not have state funding to contribute, so they are not included in this calculation. 9 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 Among these 18 states, respondents commonly indicated that state funds are distributed based on past performance, but sometimes given different “weights” than the federal funds. Other states in this category use the funds in completely different ways. Examples of these uses include providing funds to supplement what federal funds do not cover, or providing a portion of services solely on a specific population, such as young adults, or for a specific program model. Table 5. Division of States by Distribution Method of Adult Education State Funding States 8 How State Funding for Local Adult Education Providers is Determined Funding to locals is determined by a formula that takes into account a combination of enrollments, eligible population, and past performance. (ID, KS, LA, NV, NC, ND, SC, WI) Funding to locals is determined by a formula that takes into account only one of the following: enrollments, eligible population, and past performance. (AR, MI, UT, VT) None of the above are used to determine the amount of funding that flows to local providers. (CA, CT, MN, NY, OK, VA, WA) 4 6 States Profiles: LA, IN, KY Commentary How states distribute federal and state funding to local providers can be an important policy lever for aligning adult education resources with a state’s priorities. Through the design of the state RFP, which dictates how funding flows to local providers, states can incent innovation or encourage a particular type of instruction or service delivery. For example, if funds are awarded to local programs on the basis of the number of GED passers they produce, programs have a strong incentive to help more people pass the GED. If program funding is awarded in part on how many students transition to postsecondary education (and/or complete a certificate or degree program down the line), local providers will be incentivized to focus on ways to improve their transition programming, perhaps sparking new relationships with community colleges or local job training providers. A number of states appear to be using some version of a performance funding system to distribute funds to local providers. 13 This innovative funding mechanism can be used to determine funding based on program outcomes versus simply student demographics or characteristics. While the use of performance funding in adult education is not new, there are few studies that address it. The most extensive report on the topic is a 2007 report from MPR conducted on behalf of the U.S. Department of Education that examined the funding formulas, 13 Harnisch, Thomas. Performance-based Funding: A Re-Emerging Strategy in Public Higher Education Financing, American Association of State Colleges and Universities, June 2011. http://www.congressweb.com/aascu/docfiles/Performance_Funding_AASCU_June2011.pdf 10 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 implementation processes, evaluation processes in three states: Indiana, Kansas, and Missouri.14 The National Adult Education Professional Development Consortium (NAEPDC) has also collected examples of state performance funding formulas.15 Since these reports have been released, innovations in funding mechanisms in higher education are increasingly being used and spreading to other systems—such as career and technical education and adult education—as a greater number of states recognize that these systems should be working together to help students at all skill levels reach for higher goals. Furthermore, since states report using the measures in the NRS as partial drivers of evaluation criteria for funding, the federal government may want to consider how these measures are driving policy beyond just compliance. In fact, changes in the NRS being implemented in July 2012 may already have an impact in some states. These new changes shift some performance measures from goal-oriented measures to cohort measures. Currently, an adult education student is only tracked toward achieving the outcomes that they set as a goal. Starting on July 1, 2012, states will be required to report on cohorts of students toward the achievement goals. For example, instead of only tracking employment outcomes for adult education students who articulate a goal of entering employment, all unemployed students will be tracked as whether they entered employment after exit from the program. This aligns AEFLA performance measures more closely with workforce development programs and may allow states to think more broadly about incentivizing programs that help students meet longer-term goals, such as receiving additional workforce training, entering employment, or earning a postsecondary credential.16 Key Questions for Further Research Are certain provider types more likely to receive funds using a given grant process or grant criteria? For states that use performance funding, how often do these formulas change to adjust to the state’s new priorities or new student demands or interests? To what extent are the performance indicators used in these funding distribution formulas driving a focus on GED preparation and on educational functioning level gains, instead of longer-term outcomes?17 What are the outcomes of states that set higher bars for achievement (e.g. postsecondary transition, employment, or credential attainment) and hold programs accountable for these outcomes? How can these higher-level outcomes be incorporated into distribution formulas without resulting in “creaming”? 14 http://www.mprinc.com/products/pdf/Performance_Based_Funding_in_Adult_Ed.pdf http://63.117.44.95/resource_library/financial_systems/performance_funding.html 16 Information about these new NRS changes can be found in the NRS Implementation Guide 2012: http://wdcrobcolp01.ed.gov/CFAPPS/OVAE/NRS/guidelines/AssessmentPolicyGuidance.docx. 17 Educational functioning levels are used to measure the basic skills gains of adult education participants. A “gain” from one level to another is assessed by a student’s performance on a basic skills assessment, such as TABE, CASAS, WorkKeys, or BEST (ESL only). Educational functioning levels for English speakers (ABE, ASE) are also assigned grade level equivalents, e.g. 0 – 12.9). 15 11 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 SPECIAL FUNDING FOR LOCAL INNOVATION IN POSTSECONDARY TRANSITION AND ALIGNMENT The goals of adult education are changing nationally, placing greater demands on states and local programs to help students reach longer-term goals, such as moving up in the workforce or earning postsecondary credentials. To meet these ambitious goals, states are working across systems to deliver programs that can leverage the strengths of other agencies and institutions, such as workforce development and community colleges. The U.S. Department of Education has also focused significantly on alignment in collaboration with other agencies, such as the departments of Labor and of Health and Human Services. At the lower tier of instruction, these partnerships are developed to deliver high-quality instruction that is contextualized to the high demand jobs in the area and incorporate work readiness (SCANS) skills enabling the low level learner to not only gain educational skills but begin the on ramp to upper tier opportunities. At the upper tier, these partnerships are often developed to deliver high-quality instruction that enables students to take postsecondary-level courses either alongside their basic skills classes or subsequently, without needing to enroll in remediation at the community college after they leave adult education. Program models that support these goals are often called “career pathway” or “bridge” programs and can include instructional practices such as co-enrollment in adult education and postsecondary classes, team teaching (with a basic skills teacher and a technical/academic postsecondary faculty member), contextualization, and dual enrollment. Since resources for adult education are already scarce, states and institutions must often find new sources of funding to support these new programs. In a time of declining resources, many states have had to be creative about how to continue supporting innovation while still maintaining existing levels of service to students in the state. When asked in our survey if they had special sources of funding to support these innovations, nineteen states said that they have discretionary resources available to incent local innovation such as dual enrollment in postsecondary coursework, team teaching, contextualization, workplace literacy, or others. Some states use more than one funding source or use discretionary funding from different levels of government. Below is a table of the sources of funds used by these states and the number of states that report using each source. Table 6. Discretionary Resources Used to Incent Innovation Federal WIA Title II – State Leadership Funding (8) WIA Title II – Grants to Local Providers (3) WIA Incentive Funds (4) WIA Title I Discretionary Funds (2) Wagner-Peyser (1) 12 State State Adult Education Funding (2) Special Funds from the State Legislature (4) Local Community Colleges (1) Foundations and Business (1) CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 State Profiles: TX, VA, WA, MN Commentary While only nineteen states reported that they have special funding available for incenting innovation, based on information collected outside the scope of this survey, it is evident that many other states are creatively utilizing a wide variety of funding sources to support this type of innovation. Due to restrictions on the comingling of federal adult education funds with other funding sources, some states and local programs are “braiding” multiple sources of funds to develop a more sustainable funding stream to serve students with low-basic skills. While braided models typically are comprised of funding from a variety of different programs, together, they can build a formidable source of funds with which to deliver programs. In addition, states that use braided funding say that the benefits are beyond financial; the process also facilitates joint collaboration between state agencies and divisions and can ensure that all have a stake in ensuring success of the program or initiative. Key Questions for Further Research In a time of scarce resources, how can adult education programs better leverage business and employer funding? Must states count such private funds in their “maintenance of effort” reporting to the federal government? What is the most common use for these other funding resources that adult education funding cannot provide, either due to legal restrictions or scarcity of funding? Are states administered by a certain agency more likely to leverage related funding streams—for example, are states that are administered by the workforce system more likely to have access to workforce dollars? Are these funding partnerships easier to do when systems are governed by the same agency? STATE TUITION AND FEE POLICIES FOR ADULT EDUCATION COURSES Historically, adult education programs have been provided for free or at a low-cost since students in these courses are typically disadvantaged and low-income, often with significant family responsibilities. However, programs that receive federal WIA Title II funds are allowed to charge tuition/fees to students provided that they are “necessary and reasonable and do not impose a barrier to the participation of disadvantaged persons that the program was designed to serve.”18 See “Frequently Asked Questions on Adult Basic Education State Grant Administration,” U.S. Department of Education. http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ovae/pi/AdultEd/dael-faqs.pdf. 18 13 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 To better understand the landscape of tuition policies that dictate state and local program decisions, we asked states about existing policies for charging tuition/fees for adult education courses, including those for adult basic education, adult secondary education, and English language services. We defined tuition/fees as costs beyond those for class materials, which are often charged to students to cover the expenses for textbooks or other materials. We also explicitly excluded from tuition/fees in this question the cost of taking the GED test. (Findings about the cost of the GED to students and expected changes to state policy in light of the new GED assessment in 2014 can be found on page 14.) All of the survey states fit into three categories across the spectrum of charging tuition and fees: (1) states that require local programs to charge tuition/fees and set the amount, (2) states that allow programs to charge tuition/fees and (3) states that allow local programs to charge tuition/fees. Table 7. State Tuition and/or Fee Policies States 2 Tuition and/or Fee Policy Require local programs to charge fees and set the tuition/fee level (HI, WA) 21 Allow programs to charge tuition/fees19 (AZ, CA, CO, IL*, IN, IA, KS, MD*,MI, MN, MO, NE, NV, NH*, OK, RI, SC, TX*, UT, VA, WY) 20 Prohibit local programs from charging tuition/fees (AL, AR, CT, DE, GA, ID, KY, LA, MA, MS, MT, NY, NC, ND, OH, PA, SD, TN, VT, WI) *Only allow fees for students with skills at the 9th grade level or above and/or ESL students. Average Tuition Levels While most states allow local programs to determine fee levels, two states set a statewide required fee amount.20 One of the states that requires and sets fee levels $10 or less per course and the other state requires a $25 per quarter tuition charge. The latter, however, administers adult education programs through the community and technical college system and permits local colleges to waive this fee for students with limited economic means. Just under half of the states (21) indicate that they allow programs to charge tuition/fees. Of these, four (4) states indicate that they only allow programs to charge tuition/fees for students at higher skill levels, such as those in Adult Secondary Education (9th grade level and above) that are often preparing for the GED® or for ESL students. The remaining states in this category report that, though they allow programs to charge fees, few programs actually do and the state may still play a role in determining the appropriateness and level of fees. One state says that the maximum tuition and fee level is set by state statute and another reports that all proposed tuition 19 Three (3) of these states allow fees for only higher-level students, at the 9th grade level and above. Though the state did not respond to the survey, Florida also requires and sets tuition levels for adult education students. 20 14 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 and fee charges must be approved by the state. In addition, just under half of the states (20) report that they prohibit local programs from charging tuition/fees. State Profiles: WA, FL Commentary Charging tuition or fees for courses may be an attractive option for state agencies or legislatures seeking to close budget gaps. However, findings from this survey and a recent survey of adult education practitioners and program administrators suggests that states should proceed with caution when instituting these new policies. According to an informal survey facilitated by the LINCS listserv, proponents of tuition or fees say that charging students a modest tuition helps them feel more engaged in their education. It can also lead a shift to managed enrollment as fees are easier to collect on a regular schedule. This shift may support a greater focus on “bridge: programs, which are typically taught in cohorts rather than the traditional open-entry/open-exit model of adult education. Tuition can also represent a modest and consistent revenue stream for programs struggling with funding. On the other hand, charging a level of tuition that is too high or not providing waivers for tuition can lead to drops in enrollment, as adult education students are often very low-income. In addition, while some practitioners believe that charging a modest amount can lead to increase persistence and more serious study, without additional supportive services, tuition alone may not result in a significant increase in persistence or completion. Lastly, many adult education programs are often thinly staffed and collecting and enforcing tuition can sometimes be more costly than the revenue it brings in. Key Questions for Further Research Given plunging state revenues, could states institute fees that would not deter their students to gather more revenue for the program? What tuition/fee level is the “right” fit? Should students at different levels be charged different fees? Should some students be charged higher rates based on their program type? At what break-even point does the cost of collecting and tracking fees off-set the revenue produced? There is significant overlap in the role played by developmental education and adult education, yet, as the survey responses show, adult education generally charges very little, if at all. In states in which the adult education system is governed by the postsecondary system, are there systemic reasons why a student might be served in one system over another? Should there be a more systematic way of driving students to free or low-cost adult education programs (and with them, driving resources) instead of costly developmental education? What changes would need to be made on the adult education system side to facilitate this type of process? 15 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 Given that some states do not allow charging for instructional expenses, how many states are permitting these charges? What is the range and average of these charges? Assuming that this is contributing to local funding, how much revenue is received in this manner? STATE RESPONSES TO CHANGES IN THE GED® Brief Overview of Change in GED® Assessment One of the most significant recent developments in the field is the development of a new GED® assessment that will be introduced in January 2014. This new assessment, which will be aligned with the Common Core Standards, will replace the 2002 version of the GED® in both content and in form. The new assessment will be taken on a computer; the paper version will only be available in limited instances or for those needing an accommodation for a disability. The state agency will no longer administer the test directly, but states may continue to be responsible for administrative matters, such as issuing diplomas and transcripts and may have a role in selecting which programs can proctor the test. The content of the test is also being updated to align with the Common Core Standards that have been adopted by 45 states and the District of Columbia for their K-12 systems.21 Typical GED® Testing Fees Although most states report that adult education course fees are generally offered at a low cost to students, those students who wish to take the GED® must often pay fees that cover the cost of administering the test and processing the credential. States generally fall into three categories: (1) states that charge a flat, uniform fee for the test, (2) states that allow local programs to determine the cost for students, and (3) states that do not charge for the GED® test. Table 8. State GED Testing Fee Policies States 27 13 3 GED® Testing Fee Policies Charge students a flat, uniform fee for the GED® test (AL, CT, DE, GA, HI, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, MD, MA, MS, MT, NV, NH, NC, OH, RI, SC, SD, UT, VT, VA, WA, WI) Allow local programs to determine the cost for students (AZ, CA, CO, LA, MI, MN, NE, ND, OK, PA, TN, TX, WY) Do not charge for the GED® test (AR, MO, NY) 21 Alaska, Nebraska, Texas, and Virginia have not adopted the Common Core Standards. Minnesota has not adopted the Math portion, as it maintains that its existing standards for Math are higher than what the Common Core requires. 16 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 Cost of the GED® to Students The majority of states that responded to this question report that they charge a flat, uniform fee for the test. Since students who take this assessment must successfully pass a battery of five tests, typically the state institutes a fee for each of the five content area tests and, in some cases, gives students who take all five content areas a “discount.” The average costs reported below are for the full battery of five GED® content area tests, which are all required should a student wish to be certified as holding a GED®. The table below shows the range of fees to students in the states that do not offer free GED® testing. Furthermore, many first-time test-takers must repeat one or more of the content area tests. Some states reported that “re-taking” is free or provided at a minimal cost to the student. Only one state reported that re-testing is as high as $20-$25 per content area test. Current GED® Cost Compared to New Cost Structure Figure 3 shows the GED testing fee by state among states that have a flat fee. Of these states with a flat fee, 11 charge $60 or less, 15 charge $61 – 119, and only two charge $120 or more.22 Across all of these states, the average cost is $71. According to the state responses in this survey, a fee of $120 for the full battery of five tests would result in an increased cost to the student in nearly every single state. Georgia Wisconsin Iowa Idaho South Dakota Indiana Hawaii Utah Kansas South Carolina Median Value Washington Vermont Mississippi Delaware New Hampshire Massachussetts Nevada Kentucky Virginia Rhode Island Montana Illinois Alabama Maryland Ohio North Carolina Connecticut $13 $- $20 $25 $65 $65 $60 $60 $58 $55 $55 $50 $50 $45 $40 $40 $60 $85 $85 $80 $75 $75 $75 $75 $75 $80 $100 $100 $95 $95 $95 $100 $120 $120 $128 $140 Figure 3. GED Testing Fees for States with a Flat Fee 22 Georgia, one of the states that charges $120 or above, is a pilot state for the CBT GED test and thus, has already instituted the higher testing fee. 17 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 Soon, the GED Testing Service will institute a new price structure. The new cost will be $24 per test, for a total of $120 for a full battery of five tests. Re-taking any of the content area tests will cost an additional $24 per test. These costs are for the existing test and may increase when the new assessment is launched in 2014. For the vast majority of students, a GED testing fee of $120 for the full battery of tests will represent a stark cost increase. State Actions to Keep the GED Affordable for Students Currently, the state administers the GED test and most states are not prohibited from using state funding to make the test more affordable for students.23 However, currently, only 14 of the 42 states who responded to this question say that they use state funding to make the test more affordable for students. In some cases, this state funding is indirect—states pay for salaries or other program costs so that local programs can keep the cost to students down. Twenty-nine states report that they do not use state funding to make the GED more affordable for students. In these states, other funding, such as Workforce Investment Act Incentive Grants or private corporate donations, to provide the GED to students for free in certain situations or during certain times of the year. We also asked states if they expected any changes in state policy in light of the changes to the GED in 2014. Interestingly, while only 14 states responded that they currently use state funding to make the GED more affordable for students, 21 states responded that they anticipate changes in state policy to keep GED testing fees more affordable for students after 2014. While it is too early for states to have definitive information, states report that they are actively discussing options such as: Allocating more funding at the agency level to help offset the cost of the test to students, Pursuing changes in state law that would prohibit funds being used to subsidize the test, or Working with other state systems, such as workforce development or social services, to identify new resources for GED test-takers. States 21 22 Plans to Keep the GED Affordable for Students after 2014 States anticipate changes to state policy in order to continue to help keep the GED affordable for students. States do not anticipate any change in state policy or are currently in discussions about this at the state level. State Actions to Seek Alternatives to the GED® Most states have an alternative high school diploma (HSED) option that requires students to meet certain criteria that can include a combination of taking an assessment (can include the GED), completing high school credits, or completing college-level credits at a community college, or demonstrating skills and knowledge earned through experience through a student 23 State law prohibits New York from charging for the GED test. 18 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 portfolio. These existing options are not used widely in all the states due in part to the brandrecognition of the GED® as the standard secondary school equivalency exam and the lack of awareness among students about these state-recognized alternatives. As the new assessment is still a year and a half from implementation, most states note that it is too early to determine what changes are likely to be made to state policy. However, nine states report that they are exploring providing new options to students as an alternative to the GED®.24 These options range from an entirely new third-party assessment to boosting the popularity of existing alternatives, such as state-recognized high school equivalencies. These conversations are almost entirely driven by the expected increase in the cost to students and the interest of the state in having an accessible and affordable option for adults and youth to obtain a secondary high school credential if they are unable to receive a traditional high school diploma. However, other considerations include the accessibility of the new, computer-based test and the ability of students to quickly adapt to the higher academic standards of the new GED assessment. State Profiles: KY, NY, WI Commentary The upcoming change in the GED® is one of the most significant developments to occur in the adult education field in decades. While the implications of this change are not yet known, the vast majority of states express serious concern about what these changes will mean for students. While most states indicate that they do not use state funding to make the test more affordable for students, state policies that prohibit or limit fees are clearly serving this purpose. Indeed, policies that make the process of going back to school or obtaining a high school equivalency simpler and less costly yield great economic, social, and health returns across the country. Nationally, adults without a high school diploma can cost the federal government $671 each year in temporary cash assistance and in-kind benefits such as Medicaid, food stamps, and housing subsidies—but by supporting these individuals to obtain a high school diploma or a secondary school equivalent, this negative revenue could turn into an increase of over $5,400 in net taxes collected per student (that is, total federal and state taxes less the value of cash and non-cash transfers).25 Furthermore, educational attainment is one of the most important factors determining an individual’s wellbeing and that of their children. This return to investment of education is also replicated at the state level. Given the consequences of this shift to a likely more expensive test, states and the federal government should consider the implications of a drop in the number of students who are able to obtain high school equivalencies and the resulting drop in economic success. As noted above, many states are taking pro-active measures to identify and lift up existing, lower-cost 24 A group of more than twenty states are exploring alternatives through a task force of the National Council of State Directors of Adult Education, however only nine states reported in this survey that they were seeking an alternative assessment. 25 Ishwar Khatiwada, Joseph McLaughlin, and Andrew Sum, with Sheila Palma, ―The Fiscal Consequences of Adult Educational Attainment, prepared for the National Commission on Adult Literacy, December 2007, http://www.nationalcommissiononadultliteracy.org/content/fiscalimpact.pdf. 19 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 alternatives. Challenges for these states will include the time it takes to develop such an assessment and the lack of brand recognition that the GED® enjoys among students nationally. Key Questions for Further Research Beyond the cost increase, what are the other implications for running the GED® test outside of the state administrative structure? To what extent can private or other federal funds, such as workforce funds, be used to support the cost of the GED®? How can federal policy mitigate the potential issues that may arise with a new private structure of the GED? CONCLUSION Adult education is facing monumental financial and policy challenges, just as the system is becoming more important than ever for individuals and the economy alike. Declining state support, stagnant federal funding, and changes to the GED that are likely to raise costs overall, could further threaten the ability of the system to continue to provide education at existing levels. Considering that only two million of the potentially 93 million adults that could benefit from services actually receive them, the nation risks perpetuating a generation of undereducated adults if it does not drastically increase support for adult education. Recent evidence from one state that instituted stringent tuition policies and concerns from practitioners nationwide about the ability of students to afford a new, more expensive GED, suggest that raising costs to students should not be a part of the revenue mix. Instead, the federal government and states should re-examine their priorities and the return on investment that adult education can provide through increased income and sales tax revenue, increased education for the children of these adults, and improved health and safety outcomes. With a secondary and postsecondary education more important than ever in our nation’s history, now is not the time to deny workers, English language learners, and out-of-school youth educational opportunity and economic success. 20 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 Appendix A Percentage of Funding by Revenue Source State Local State Federal Tuition Alabama Alaska Arizona Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut Delaware District of Columbia Florida Georgia Hawaii Idaho Illinois Indiana Iowa Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Montana Nebraska Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina North Dakota Ohio Oklahoma 0 *** 0 0 0 40 44 0 *** *** 7 0 0 0 11 0 28 0 0 *** 26 20 0 0 0 0 36 25 4 23 *** *** 0 0 0 15 0 33 *** 0 80 88 0 45 28 *** *** 38 60 29 64 49 0 20 71 40 *** 31 60 60 88 32 35 21 10 70 50 *** *** 72 87 65 29 25 67 *** 0 20 12 60 11 72 *** *** 55 40 71 36 40 100 52 29 60 *** 42 20 40 12 68 65 43 65 24 22 *** *** 28 13 35 56 75 0 *** 0 0 0 0 0 0 *** *** 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 *** 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 5 *** *** 0 0 0 0 0 21 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 Percentage of Funding by Revenue Source State Local State Oregon *** *** Pennsylvania 15 32 Rhode Island 10 70 South Carolina 0 0 South Dakota 0 10 Tennessee 10 15 Texas 0 25 Utah 0 75 Vermont 0 81 Virginia 15 25 Washington 0 58 West Virginia *** *** Wisconsin 43 22 Wyoming 0 63 9 45 Total Notes: *** The state did not participate in the survey. 22 Federal Tuition *** 53 20 0 90 75 75 25 19 53 16 *** 35 37 45 *** 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 26 *** 0 0 1 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 Appendix B State Tuition Policies State Response Alabama Alaska Prohibits *** Arizona Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut Delaware District of Columbia Florida Georgia Hawaii Idaho Illinois Indiana Other Prohibits Allows Allows Prohibits Prohibits Iowa Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maine Allows Allows Prohibits Prohibits *** Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Other Prohibits Allows Minnesota Mississippi Allows Prohibits Missouri Montana Nebraska Allows Prohibits Allows 23 *** *** Prohibits Requires Allows Allows Allows Additional Details *** State allows local program to charge supplemental class fees, based on a sliding scale, but does not allow local programs to charge tuition. Schools may charge a small fee, commonly a "registration fee." *** *** $10 fee for enrollment in ABE, ASE, and ESOL. No more than $3 per unit of instruction at the ASE level only. Some local programs have recently started charging class fees, but this will be the first year that data will be collected. *** State allows local programs to charge fees or tuition for upper level students only, and does not set fees, but issues a policy that fees may not present a barrier to participation. Most programs do not charge, but a few charge a minimal materials fee. The amount charged by the local program has to be approved by the state AEL office. Maximum charge per year per student is $25. CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 State Tuition Policies State Response Additional Details Allows Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina North Dakota Ohio Other *** *** Prohibits Prohibits Prohibits Prohibits Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania Rhode Island South Carolina South Dakota Tennessee Allows *** Prohibits Allows Allows Prohibits Prohibits Other Texas Allows Prohibits Allows Utah Vermont Virginia Programs can charge for educational services above the ABE level (8th grade functioning level). *** *** Oklahoma only has two programs that charge an enrollment processing fee. *** State allows local programs to charge a minimal fee to Adult Secondary Students (grades 9-12 reading level) only. Amount is locally determined. By state statute, programs may charge up to $100 per client per program year. Any fees are set by the local boards of education or local boards of trustees The state requires a tuition charge of $25 and requires that each college have a waiver policy for students with limited economic means. *** Requires Washington *** West Virginia Prohibits Wisconsin Allows Wyoming Notes: *** The state did not participate in the survey. 24 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 Appendix C State Policies on GED Testing Fees Uses State Funding to Keep the GED® Test Affordable for Students Anticipates changes in state policy on keeping GED® testing fees affordable for students after the new assessment in 2014 50 *** Varies by Local Program 0 (No charge) Varies by Local Program Varies by Local Program 13 75 No *** No *** *** No Yes Yes Yes No No No No Yes No No Yes *** *** *** *** *** *** *** No No Yes No Yes No No No No Yes No Yes Yes No No Yes Yes No *** No Yes *** Yes Yes No No Yes Yes No No No No No Yes Cost for Full Battery of GED® Tests State Alabama Alaska Arizona Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut Delaware District of Columbia Florida *** 95 (paper)/160 (CBT) Georgia 95 Hawaii 100 Idaho 50 Illinois 70(paper)/120(CBT) Indiana 100 Iowa 85 Kansas 60 Kentucky Varies by Local Program Louisiana *** Maine 45 Maryland 65 Massachusetts Varies by Local Program Michigan Varies by Local Program Minnesota 75 Mississippi 0 (No charge) Missouri 55 Montana 25 CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE) Seeking alternative assessment *** Sinking or Swimming: Findings from a State Survey of Adult Education Tuition and Financing Policies 2012 State Policies on GED Testing Fees Uses State Funding to Keep the GED® Test Affordable for Students Anticipates changes in state policy on keeping GED® testing fees affordable for students after the new assessment in 2014 No No No Yes 65 Yes Yes *** *** 0 (No charge) *** *** Yes *** *** Yes *** *** 25 Yes Yes No Yes No No No Yes *** *** No No Yes Yes No Yes Cost for Full Battery of GED® Tests State Nebraska Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina North Dakota Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania Rhode Island South Carolina South Dakota Varies by Local Program 60 Varies by Local Program 40 Varies by Local Program *** Varies by Local Program 55 80 95 No Varies by Local No Program Tennessee Varies by Local No Program Texas 85 No Utah 75 Yes Vermont 58 Yes Virginia 75 Yes Washington *** *** West Virginia 120 No Wisconsin Varies by Local No Program Wyoming Notes: *** The state did not participate in the survey. 26 Seeking alternative assessment *** No No No No Yes Yes Yes *** No *** No CLASP/National Council of State Directors of Adult Education (NCSDAE)