Nature-vs-Nurture-argument

advertisement

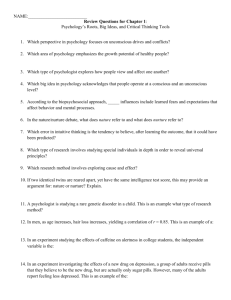

Nature vs. Nurture Argument Basic essay structure in argument form, TEA paragraph structure, Works Cited page Doc. 1 (nurture) Anzalone, Charles. "Literacy Depends on Nurture, Not Nature, UB Education Professor Says." - University at Buffalo. 13 Nov. 2013. Web. 8 Dec. 2014. BUFFALO, N.Y. — A University at Buffalo education professor has sided with the environment in the timeless “nurture vs. nature” debate after his research found that a child’s ability to read depends mostly on where that child is born, rather than on his or her individual qualities. “Individual characteristics explain only 9 percent of the differences in children who can read versus those who cannot,” says Ming Ming Chiu, lead author of an international study that explains this connection and a professor in the Department of Learning and Instruction in UB’s Graduate School of Education. “In contrast, country differences account for 61 percent and school differences account for 30 percent,” Chiu says. Therefore, he concludes, the country in which a child is born largely determines whether he or she will have at least basic reading skills. It’s clearly a case where “nurture” — the environment and surroundings of the child — is more important than “nature” — the child’s inherited, individual qualities, according to Chiu. More than 99 percent of fourth-graders in the Netherlands can read, but only 19 percent of fourth-graders in South Africa can read, Chiu notes. “Although the richest countries typically have high literacy rates exceeding 97 percent,” he says, “some rich countries, such as Qatar and Kuwait, have low literacy rates — 33 percent and 28 percent, respectively.” The study, “Ecological, Psychological and Cognitive Components of Reading Difficulties: Testing the Component Model of Reading in Fourthgraders Across 38 Countries,” analyzed reading test scores of 186,725 fourth-graders from 38 countries, including more than 4,000 children from the U.S. Chiu and co-authors Catherine McBride-Chang of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Dan Lin of the Hong Kong Institute of Education published the study in the winter 2013 issue of the Journal of Learning Disabilities. The educators used data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Program for International Student Assessment. Besides showing that the country of origin was a better predictor of reading skills than individual traits, the study also showed that other attributes at the child, school and country levels were all related to reading. First, girls were more likely than boys to have basic reading skills, Chiu says. Children with greater early-literacy skills, better attitudes about reading or greater self-confidence in their reading ability also were more likely to have strong basic reading skills. “Children were more likely to have basic reading skills if they were from privileged families, as measured through socioeconomic status, number of books at home and parent attitudes about reading,” says Chiu. “Also, children attending schools with better school climate and more resources were more likely to have basic reading skills. “Our U.S. culture values ‘can-do’ individualism, but we forget how much depends on being lucky enough to be born in the right place,” he says. Doc. 2 (both) "Nature vs. Nurture." Nature vs Nurture. Diffen. Web. 8 Dec. 2014. The nature versus nurture debate is about the relative influence of an individual's innate attributes as opposed to the experiences from the environment one is brought up in, in determining individual differences in physical and behavioral traits. The philosophy that humans acquire all or most of their behavioral traits from "nurture" is known as tabula rasa ("blank slate"). In recent years, both types of factors have come to be recognized as playing interacting roles in development. So several modern psychologists consider the question naive and representing an outdated state of knowledge. The famous psychologist, Donald Hebb, is said to have once answered a journalist's question of "Which, nature or nurture, contributes more to personality?" by asking in response, "Which contributes more to the area of a rectangle, its length or its width?" Comparison chart Nature What is In the "nature vs nurture" debate, nature refers to an it? individual's innate qualities (nativism). Nature is your genes. The physical and personality Example traits determined by your genes stay the same irrespective of where you were born and raised. Factors Biological and family factors Nurture In the "nature vs nurture" debate, nurture refers to personal experiences (i.e. empiricism or behaviorism). Nurture refers to your childhood, or how you were brought up. Someone could be born with genes to give them a normal height, but be malnourished in childhood, resulting in stunted growth and a failure to develop as expected. Social and environmental factors Nature vs. Nurture in the IQ debate Evidence suggests that family environmental factors may have an effect upon childhood IQ, accounting for up to a quarter of the variance. On the other hand, by late adolescence this correlation disappears, such that adoptive siblings are no more similar in IQ than strangers. Moreover, adoption studies indicate that, by adulthood, adoptive siblings are no more similar in IQ than strangers (IQ correlation near zero), while full siblings show an IQ correlation of 0.6. Twin studies reinforce this pattern: monozygotic (identical) twins raised separately are highly similar in IQ (0.86), more so than dizygotic (fraternal) twins raised together (0.6) and much more than adoptive siblings (almost 0.0). Consequently, in the context of the "nature versus nurture" debate, the "nature" component appears to be much more important than the "nurture" component in explaining IQ variance in the general adult population of the United States. Nature vs. Nurture in Personality Traits Personality is a frequently cited example of a heritable trait that has been studied in twins and adoptions. Identical twins reared apart are far more similar in personality than randomly selected pairs of people. Likewise, identical twins are more similar than fraternal twins. Also, biological siblings are more similar in personality than adoptive siblings. Each observation suggests that personality is heritable to a certain extent. However, these same study designs allow for the examination of environment as well as genes. Adoption studies also directly measure the strength of shared family effects. Adopted siblings share only family environment. Unexpectedly, some adoption studies indicate that by adulthood the personalities of adopted siblings are no more similar than random pairs of strangers. This would mean that shared family effects on personality wane off by adulthood. As is the case with personality, non-shared environmental effects are often found to out-weigh shared environmental effects. That is, environmental effects that are typically thought to be life-shaping (such as family life) may have less of an impact than non-shared effects, which are harder to identify. Moral Considerations of the Nature vs. Nurture Debate Some observers offer the criticism that modern science tends to give too much weight to the nature side of the argument, in part because of the potential harm that has come from rationalized racism. Historically, much of this debate has had undertones of racist and eugenicist policies — the notion of race as a scientific truth has often been assumed as a prerequisite in various incarnations of the nature versus nurture debate. In the past, heredity was often used as "scientific" justification for various forms of discrimination and oppression along racial and class lines. Works published in the United States since the 1960s that argue for the primacy of "nature" over "nurture" in determining certain characteristics, such as The Bell Curve, have been greeted with considerable controversy and scorn. A recent study conducted in 2012 has come up with the verdict that racism, after all, isn't innate. A critique of moral arguments against the nature side of the argument could be that they cross the is-ought gap. That is, they apply values to facts. However, such appliance appears to construct reality. Belief in biologically determined stereotypes and abilities has been shown to increase the kind of behavior that is associated with such stereotypes and to impair intellectual performance through, among other things, the stereotype threat phenomenon. The implications of this are brilliantly illustrated by the implicit association tests (IATs) out of Harvard. These, along with studies of the impact of self-identification with either positive or negative stereotypes and therefore "priming" good or bad effects, show that stereotypes, regardless of their broad statistical significance, bias the judgements and behaviours of members and non-members of the stereotyped groups. Real Traits It is sometimes a question whether the "trait" being measured is even a real thing. Much energy has been devoted to calculating the heritability of intelligence (usually the I.Q., or intelligence quotient), but there is still some disagreement as to what exactly "intelligence" is. Determinism and Free Will If genes do contribute substantially to the development of personal characteristics such as intelligence and personality, then many wonder if this implies that genes determine who we are. Biological determinism is the thesis that genes determine who we are. Few, if any, scientists would make such a claim; however, many are accused of doing so. Others have pointed out that the premise of the "nature versus nurture" debate seems to negate the significance of free will. More specifically, if all our traits are determined by our genes, by our environment, by chance, or by some combination of these acting together, then there seems to be little room for free will. This line of reasoning suggests that the "nature versus nurture" debate tends to exaggerate the degree to which individual human behavior can be predicted based on knowledge of genetics and the environment. Furthermore, in this line of reasoning, it should also be pointed out that biology may determine our abilities, but free will still determines what we do with our abilities. Doc. 3 (nature) "Grades more Nature than Nurture" BBC News. 11 Dec. 2013. Web. 8 Dec. 2014. Exam grades 'more nature than nurture' Genetic influence explains almost 60% of the variation in GCSE exam results, twin studies suggest. Scientists studied academic performance in more than 11,000 identical and non-identical 16-year-old twins in the UK. The team from King's College London found that on average, genes explained 58% of differences between GCSE scores in core subjects such as maths. Differences in grades due to environment, such as schools and families, accounted for about 36%. The remaining differences in GCSE scores in maths, English and science are explained by environmental factors unique to each person, say the researchers. Environment 'still influential' Study leader Nicholas Shakeshaft, from the Institute of Psychiatry at King's, said: "Our research shows that differences in students' educational achievement owe more to nature than nurture. While the genetic influence is slightly more than 50% that still leaves a massive role for environmental factors” "Since we are studying whole populations, this does not mean that genetics explains 60% of an individual's performance, but rather that genetics explains 60% of the differences between individuals, in the population as it exists at the moment. "This means that heritability is not fixed - if environmental influences change, then the influence of genetics on educational achievement may change too." The researchers studied two sets of twins - identical and non-identical - to help distinguish between the effects of nature and nurture at the age of 16. If identical twins' scores at GCSE are more alike than those of non-identical twins, it can be assumed that genetics plays a bigger role than the shared environment - attending the same school and family influences. Professor Robert Plomin, director of the Twin Early Development Study, also from the Institute of Psychiatry, said it was important to recognise the major role that genetics plays in children's educational achievement. "It means that educational systems which are sensitive to children's individual abilities and needs, which are derived in part from their genetic predispositions, might improve educational achievement," he said. Nature-nurture debate Previous research has shown large numbers of genes may be involved in academic ability, many of which have not been identified. Prof Michael O'Donovan, from the Medical Research Council, which funded the research, said: "Further research is needed to assess the implications of the findings for educational strategies." Dr Simon Underdown, principal lecturer in biological anthropology at Oxford Brookes University, said the results must be treated with caution. "While the genetic influence is slightly more than 50%, that still leaves a massive role for environmental factors. "What this research does is show that complex traits like intelligence are not the product of one or two simple genes. Rather it is managed by an intricate process that relies on genetic factors and environmental influences. The nature-nurture debate is not over yet." Argument Form I. Style a. II. III. IV. V. VI. Use MLA format i. Works Cited is on a separate page ii. No title page iii. Running header (page numbering) is not necessary for this course b. Artistic Proofs i. Incorporate ethos, pathos, and logos 1. ethos—looks and sounds professional, elevated vocabulary 2. pathos—consider tone and emotional word choices throughout; incorporate an anecdote in the introduction if possible 3. logos—back up opinions with facts; use authorities to support thesis c. Avoid questions i. This is leading people, not asking for someone else’s opinion Introduction a. Topic sentence i. This is the assigned essential question written as a declarative b. Hook i. The purpose of an intro. is two-fold: 1) inform the reader about the topic, content and the author’s stance, and 2) give the reader a reason to want to read the paper. 1. Anecdotes a. An anecdote is solid way to bring interest to the subject matter; they can be used to show a need for your particular call to action 2. Strong/Funny quote a. Related to the subject matter 3. Describe the situation a. Paint the picture in a descriptive manner that gives the reader background for the issue c. Thesis i. This is the answer to the essential question in a sentence or two at the end of the paragraph. Body paragraphs in support a. Minimum of two support paragraphs b. TEA format i. Topic is a mini thesis—the point to be proved in the paragraph ii. Evidence is one good quote that helps support the thesis iii. Argument is at least three good sentences in support of the thesis 1. Do not use questions 2. Do not use “That is why…” or “I’m going to tell you about…” type sentences 3. Do use synonyms for key words in the paper’s thesis (the main thesis); it ties the paragraph to the overall purpose of the essay. Consider the opposing viewpoint a. Acknowledge strong points made by the opposing side through the course of the paper, but add a qualifier to explain why these points do not weigh as heavily as the points for the side you’ve chosen to support Conclusion a. The Call To Action! b. Give directives for action to the reader i. I.e. Read a book! Notes a. This is essentially the traditional 5 paragraph essay b. Use ethos, pathos and logos, the artistic proofs, to help elevate your ability to argue c. Include a counter argument; it’s relevant d. Only one quote per paragraph is ample; make sure that your argument portion carries the argument i. The evidence isn’t the argument; it’s back-up e. Have a separate topic and thesis and put the thesis last in the intro. paragraph f. The call to action is a nice way to finish the essay; it also gives a reason for the paper to be written—because you want people to believe or act a certain way