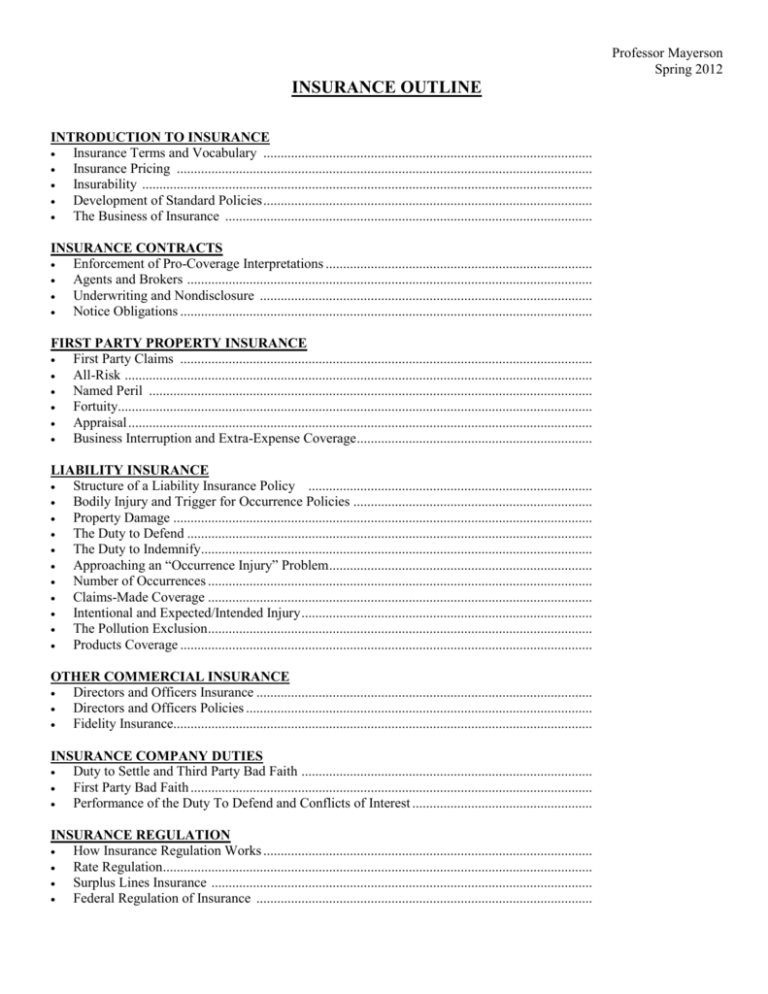

Insurance Outline – Mayerson – Spring 2012

advertisement