2101

An Introduction to Within-Subjects Analysis of Variance

In ANOVA a factor is either a “between-subjects” factor or a “within-subjects”

factor. When the factor is between-subjects the data are from independent samples,

one sample of dependent variable scores for each level of the factor. With such

independent samples we expect no correlation between the scores at any one level of

the factor and those at any other level of the factor. A “within-subjects” or “repeated

measures” factor is one where we expect to have correlated samples, because each

subject is measured (on the dependent variable) at each level of the factor.

The Headache Study

An example of a within-subjects design is the migraine-headache study

described by Howell (Fundamental Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 6th ed., p.

459). The dependent variable is duration of headaches (hours per week), measured

five times. The within-subjects factor is Weeks, when the measurement was taken,

during the third or fourth week of baseline recording (levels 1 and 2 of Week) or during

the fourth, fifth, or sixth week of relaxation training (levels 3, 4, and 5 of Week). The

resulting five samples of scores are clearly not independent samples, each is based on

the same nine subjects. Since we expect the effect of individual differences among

subjects to exist across levels of the Week factor, we expect that the scores at each

level of Week will be positively correlated with those at each other level of Week—for

example, we expect those who reported the greatest durations during the level 1 week

will also tend to report the greatest durations during the level 3 week.

Crossed versus Nested Factors

When each subject is measured at each level of a factor we say that Subjects is

crossed with that factor. For our headache example, Subjects is crossed with Week.

Mathematically we treat Subjects as a factor, so we have a Week x Subjects factorial

design with only one score in each cell (each subject is measured once and only once

at each level of Week). In ANOVA each factor is either crossed with or nested within

each other factor. When one factor is nested within another then knowing the level of

the nested factor tells you the level of the other factor. The Subjects factor is said to be

nested within between-subjects factors. For example, if I randomly assigned ten

subjects to each of five experimental groups I know that subjects 1-10 are at level one

of the between-subjects factor, 11-20 at level two, etc. If you ask me at what level of

the between-subjects factor is the score that is at level 35 of the Subjects factor, I can

answer “three.” If the experimental factor were within-subjects (each subject tested in

each of the five experimental conditions) and you asked me, “This score is from subject

number 5, at what level of the experimental factor was it obtained,” I could not tell you.

Copyright 2012, Karl L. Wuensch - All rights reserved.

WS-ANOVA-01.docx

Page 2

Counterbalancing

Suppose that our within-subjects factor is not Week, but rather some

experimental manipulation, for example, the color of the computer screen (gray, green,

white, blue, or black) upon which I present the material the subject is to learn. Each

subject is tested with each color. A big problem with such a design is that the order of

presentation of the experimental conditions may confound the results. For example,

were I to test each subject first with the gray screen, then green, then white, then blue,

and lastly black, the results (how well the subject learned the material that was

presented, such as a list of paired associates) might be contaminated by practice

effects (subjects get better at the task as time passes), fatigue effects (subjects get

tired of it all as time passes), and other such effects. While one may ameliorate such

problems by being sure that subjects are well practiced before starting the experimental

manipulations and by inserting effective rest periods between experimental conditions,

counterbalancing may be required.

In complete counterbalancing each of the possible orderings of the

experimental conditions is equally represented. If k is the number of conditions, k! is the

number of orderings. With only two conditions (A and B) there are only 2! = 2 orderings

(A then B versus B then A), so half the subjects are run with A first, half with B first. For

k = 3, there are 3(2) = 6 orderings (ABC, ACB, BAC, BCA, CAB, CBA), so you run 1/6

of the subjects with each. For k = 5 there are 5(4)(3)(2) = 120 orderings! The basic

idea of counterbalancing is to spread any order effects evenly across experimental

conditions so that order effects will not be confounded with experimental treatments. Of

course, if there is asymmetrical transfer (the effect upon B of being preceded by A is

different from the effect upon A of being preceded by B—for example, the positive effect

of having practiced sober greatly helps subsequent drunken performance, but the effect

of prior drunken practice upon later sober performance is slight) then such

counterbalancing does not solve the problem. When the number of possible orderings

is too large to for complete counterbalancing to be practical, one may employ some

form of incomplete counterbalancing where each condition appears equally often in

each position, but not all possible orderings are used. For example, for a k = 5 level

factor, run 1/5 of the subjects in each of the following orderings:

ABCDE

EABCD

DEABC

CDEAB

BCDEA

Randomized Blocks Design

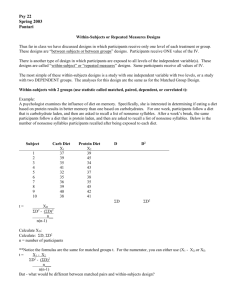

The correlation between samples may be produced by matching (also called

“blocking”) the subjects on one or more extraneous variables thought to be positively

correlated with the dependent variable and then within each block randomly assigning

one subject to each condition. Statistically the scores within each block are treated as if

Page 3

they came from the same subject, that is, the experimental factor is treated as a

within-subjects factor. Such a design is called a randomized blocks design or a

split-plot design, the latter term coming from agricultural research.

For example, suppose that I wish to evaluate the effectiveness of five different

methods of teaching the alphabet. I cannot very well use a truly within-subjects design,

unless I use electroconvulsive brain shock to clear subjects’ memories after learning the

alphabet with one method and before going on to the next method. I administer a

“readiness to learn” test to all potential subjects, confident that performance on this test

is well correlated with how much the subjects will learn during instruction. I match

subjects into blocks of five, each subject within a block having a readiness score

identical to or very close to the others in that block. Within each block one subject is

assigned to method 1, one to method 2, etc. After I gather the post-instructional

“knowledge of the alphabet” test scores, the Blocks factor is treated just like a Subjects

factor in a Method x Blocks ANOVA.

If the variable(s) used to match subjects is(are) well correlated with the

dependent variable, the matching will increase power, since the analysis we shall use

allows us to remove from what would otherwise be error variance (in the denominator of

the F-ratio for the treatment effect) the effect of the matching variable(s). Were we

foolish enough to match on something not well correlated with the dependent variable,

we could actually loose power, because matching reduces the error degrees of

freedom, raising the critical value for F.

One can view the within-subjects or repeated measures design as a special case

of the randomized blocks design, one where we have subjects matched up on

themselves! The matched pairs design, covered when we learned correlated t-tests, is

just a special case of the randomized blocks design, where k = 2.

Analysis of the Headache Data

Although Howell uses means rather than totals when computing the ANOVA, it is

easy to convert these means to totals and use the same method we learned earlier

when doing factorial independent samples ANOVA. The totals for subjects 1 through 9

(summed across weeks) are: 63, 57, 46, 97, 84, 65, 54, 49, and 81. The totals for

weeks 1 through 5 (summed across subjects) are: 187, 180, 81, 52, and 61. The sum

of all 5 x 9 = 45 squared scores is 10,483, and the simple sum of the scores is 561. The

5612

6993.8 . The total SS is then 10,483 - 6993.8 =

correction for the mean, CM, is

45

3489.2. From the marginal totals for week we compute the SS for the main effect of

1872 1802 812 522 612

6993.8 1934.5 . From the subject totals, the

Week as:

9

63 2 62 2 89 2

6993.8 833.6 . Since there is only one

SS for Subjects is:

5

score per cell, we have no within-cells variance to use as an error term. It is not

Page 4

generally reasonable to construct an F-ratio from the Subjects SS (we only compute it to

subtract it from what otherwise would be error SS), but we shall compute an F for the

within-subjects factor, using its interaction with the Subjects factor as the error term.

The interaction SS can be simply computed by subtracting the Subjects and the Week

sums-of-squares from the total, 3489.2 - 833.6 - 1934.5 = 721.1.

The df are computed as usual in a factorial ANOVA -- (s-1) = (9-1) = 8 for

Subjects, (w-1) = (5-1) = 4 for Week, and 8 x 4 = 32 for the interaction. The F(4, 32) for

1934.5 / 4

21.46 , p < .01.

the effect of Week is then

721.1/ 32

Assumptions of the Analysis

Some of the assumptions of the within-subjects ANOVA are already familiar to you—

normality of the distribution of the dependent variable at each level of the factor and

constancy in the dependent variable’s variance across levels of the factor. One

assumption is new—the sphericity assumption. Suppose that we computed

difference scores (like those we used in the correlated t-test) for level 1 vs level 2, level

1 vs level 3, 1 vs 4, and every other possible pair of levels of the repeated factor. The

sphericity assumption is that the standard deviation of each of these sets of difference

scores (1 vs 2, 1 vs 3, etc. ) is a constant. One way to meet this assumption is to have

a compound symmetric variance-covariance matrix, which essentially boils down to

having homogeneity of variance and homogeneity of covariance, the latter meaning that

the covariance (or correlation) between the scores at one level of the repeated factor

and those at another level of the repeated factor is constant across pairs of levels (1

correlated with 2, 1 with 3, etc.). Advanced statistical programs like SAS, SPSS, and

BMDP have ways to test the sphericity assumption (Mauchley’s test), ways to adjust

downwards the degrees of freedom to correct for violations of the sphericity assumption

(the Greenhouse-Geisser and Hunyh-Feldt corrections), and even an alternative

analysis (a multivariate-approach analysis) which does not require the sphericity

assumption. The data provided in Howell's Fundamentals text, by the way, do violate

the sphericity assumption. I advised him of this in 2001: "As long as I am pestering you

with trivial things, let me suggest that, in the next edition of the Fundamentals text, you

use, in the chapter on repeated measures ANOVA, the headache/relaxation therapy

data that are in the Statistical Methods text rather than those that are in the

Fundamentals text. For the data in the Fundamentals text, Mauchley's test is significant

at .009, and the estimates of epsilon are rather low. While you do address the

sphericity assumption, you do not make it clear that it is violated in the data presented in

the chapter. Of course, that gives the instructor the opportunity to bring up that issue,

which might be a plus."

Page 5

Higher-Order Designs

A design may have one or more between-subjects and/or one or more

within-subjects factors. For example, we could introduce Gender (of subject) as a

second factor in our headache study. Week would still be a within-subjects factor, but

Gender would be a between-subjects factor (unless we changed persons’ genders

during the study!). Although higher-order factorial designs containing within-subjects

factors can be very complex statistically, they have been quite popular in the

behavioural sciences.

Multiple Comparisons

In an earlier edition, Howell did protected t-tests using the formula:

t

Mi M j

1

1

MSerror

n

i nj

This is the same formula used for multiple comparisons involving a

between-subjects factor, except that the error MS is the interaction between Subjects

and the Within-subjects factor.

Of course, one might decide to make more focused comparisons, not just

comparing each mean with each other mean. For the headache data one interesting

comparison would be to compare the mean during the baseline period, (187 + 180 )/18

= 20.39, with the mean during training (81+ 52 + 61)/27 = 7.19. Using t,

20.39 7.19

t

9.14 on 32 degrees of freedom, p < .01.

1

1

22.534

18 27

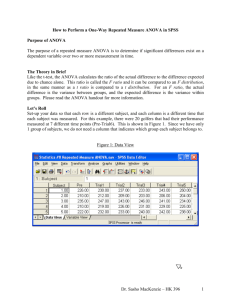

One-Way Within-Subjects ANOVA with SPSS

Copyright 2012, Karl L. Wuensch - All rights reserved.