Haroset.JOY - reformjudaismmag.net

advertisement

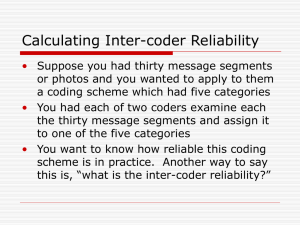

Holidays The Origins of Haroset by Steven P. Weitzman How did haroset (chopped fruit, nuts, wine, and spices) become a traditional seder food? A debate concerning haroset appears in a tractate (Pesahim 116a) from the Babylonian Talmud, compiled in Mesopotamia in the 3rd – 5th centuries C.E. The discussion begins by citing the following text: They bring before him matzah, lettuce, haroset, and two cooked dishes, even though haroset is not obligatory. Rabbi Eliezer bar Tzadok says: Haroset is obligatory. (Mishnah Pesachim 10:3) This text reflects a difference of opinion between an anonymous voice claiming belief that this practice is voluntary (“even though haroset is not obligatory”), and the voice of Rabbi Eliezer bar Tzadok, who holds that haroset is a religious observance in itself— something one has to eat as part of the scripted performance of the seder. The text is very brief, however: The Mishnah does not explain the differing viewpoints or the significance of this practice. 1 Scholars have noted that in ancient Palestine, and perhaps in the Hellenistic world, haroset was a popular appetizer, which may explain why it initially became part of the Passover ritual. Originally it may not have had a religious meaning, and served simply as a tasty part of any festive meal. This explanation, however, might have been more of a concern for the sages of Babylonia than those of Palestine because when the Passover customs outlined in the Mishnah traveled to Babylonia, the Babylonian sages did not have the cultural background to appreciate seder practices such as haroset that reflected Palestinian customs. Therefore, the practice of eating haroset had to be explained. The following discussion in the Babylonian Talmud (words in bold type are citations of the just-discussed Mishnah) aims to flesh out the differing points of view and to suggest several possible interpretations as to why haroset is eaten. “Even though haroset is not obligatory.” But if eating haroset is not obligatory, why is it served? Rabbi Ami says: Because of the kappa [a poisonous worm found in lettuce and other vegetables]. Rabbi Assi says: For the kappa of lettuce, take radishes; for the kappa of radishes—leeks; for the kappa of leeks—hot water; for all kinds of kappa—hot water. And in the meanwhile, recite the following: “Kappa, kappa, I remember you, your seven daughters, and your eight daughters-in-law.” “Rabbi Eliezer bar Tzadok says: Haroset is obligatory.” 2 Why is it a religious obligation? Rabbi Levi says: In memory of the apple tree. Rabbi Yohanan says: In memory of the mortar. Abaye says: Therefore, make it sharp-tasting, and thick—sharp, in memory of the apple tree; and thick, in memory of the mortar. As is typical of the Talmud, in this passage no attempt is made to resolve the disagreement; rather, an attempt is made to explore both sides of the dispute. If the haroset is not a religious obligation, why are we instructed to eat it on Passover? Rabbi Ami proposes that the haroset has medicinal purposes. Since eating lettuce is a religious obligation during the seder meal, and lettuce sometimes contains the dangerous worms known as kappa, the haroset is eaten to neutralize the health dangers. Rabbi Assi supplements Rabbi Ami’s interpretation with other remedies for the kappa worm. This is a good example of the breadth of the Talmud’s interest; its editors engaged not only in religious guidance, but also in practical wisdom. Some rabbis were particularly celebrated for their accomplishments in medicinal arts. The home remedies and incantation Rabbi Assi provides may have been examples of customs that Babylonian Jews shared with their non-Jewish neighbors. 3 Having made a credible case for haroset as a custom voluntarily observed because of its benefits, the Talmud now turns to the other possibility raised in the Mishnah: that it is eaten to fulfill an obligation. If so, why is it obligatory? Two possibilities are raised. Rabbi Levi interprets the haroset (made of apples) as a remembrance of the “apple tree.” This is an oblique reference to a fanciful legend in the Talmud (Sotah 11b) describing how the redemption of the Israelites from bondage in Egypt began with two miraculous instances of growing the Jewish nation. When Israelite sons were still under threat of destruction because of Pharaoh’s decree, expectant Israelite mothers went out to the apple orchards to deliver their babies and were blessed with quiet, painless births. In another midrash, when the Israelite men were reluctant to have relations with their wives for the same reason, their wives seduced them under apple trees so as to ensure the continuity of the Israelites. In other words, one is obliged to eat haroset to commemorate the apple tree’s role in the Exodus story. Rabbi Yohanan interprets the haroset differently. In his view, the texture and appearance of haroset are its most important attributes, serving as a reminder of the mortar with which the Israelite slaves built Pharaoh’s cities. The two interpretations of haroset’s religious significance point to the overlapping symbolic meanings of the seder service as a whole. On the one hand, the seder is meant 4 to celebrate redemption from slavery (here captured by the apple tree); on the other hand, it is designed to bring the memory of slavery to life (here, by putting mortar on the table). As this section of Talmudic discussion ends, both meanings of haroset are preserved. Thus, haroset becomes a potent symbol of both bondage and freedom, of suffering and redemption—a powerful example of the talmudic rabbis’ penchant for paradox and their respect for divergent interpretations of the Bible. Dr. Steven Weitzman is director of the Taube Center for Jewish Studies and Daniel E. Koshland Professor of Jewish Culture and Religion at Stanford University. This article is adapted with permission from The Jews: A History, by John Efron, Steven Weitzman, Matthias Lehmann, and Joshua Holo. Prentice Hall, 2008. 5