SHORT STORY COLLECTIONS - Intermediate Fiction Spring 2014

advertisement

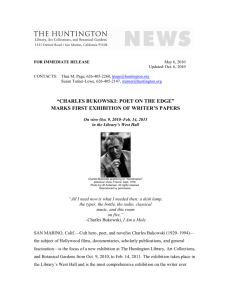

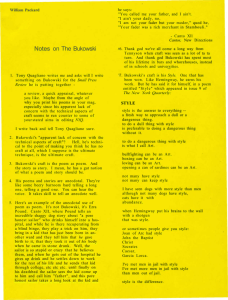

Mason Boyles English 206 Bukowski’s Hot Water Music: A Critical Analysis BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAY Charles Bukowski was a German-American poet, novelist, and short story writer. His off-the-cuff, vulgar prose earned him status as an underground hero; he has been called the “poet laureate of skid row.” His writing is cynical, satirical, and critical of the human race in general and literary academia in particular. (Daniloff) Born in Germany and raised in the Los Angeles suburbs, Bukowski was physically and emotionally abused by his authoritarian father. (“Charles Bukowski”) He chronicles his unhappy childhood in the semiautobiographical Ham on Rye. He briefly attended Los Angeles Community College before dropping out and moving to New York to pursue a career in writing. (“Charles Bukowski”) Frustrated with his lack of success, he quit for ten years and traveled the country working odd factory jobs. (“Charles Bukowski”) He began his professional writing career when he returned to L.A. His work was published in underground magazines until Black Sparrow Press picked it up. (“Charles Bukowski”) His vulgar characters and concise narrative style earned him a devoted cult following before his death in 1994. Today Bukowksi is recognized as one of the foremost poets and short story writers of the twentieth century. His work continues to be published posthumously, most recently with the books of poetry The People Look Like Flowers at Last: New Poems and Slouching Toward Nirvana. Works Cited "Charles Bukowski." Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, 2010. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/charles-bukowski>. Daniloff, Caleb. "Hanging with Bukowski at the Gotlieb Center." BU Today RSS. Boston University, 26 Mar. 2009. Web. 5 Mar. 2014. <http://www.bu.edu/today/2009/hanging-with-bukowski-at-the-gotlieb-center/>. SUMMARY Bukowski’s characters are selfish and sometimes sociopathic. They display no apparent moral prerogative, raping, killing, and maiming each other without remorse. In The Man Who Loved Elevators, a man dissatisfied with his girlfriend rapes a woman in the elevator of his apartment complex. He meets her in the elevator again the next day, but when she reciprocates his feelings he loses interest. In Head Job, a widow named Margie falls in love with her neighbor’s boyfriend. When she discovers that the boyfriend is the famous poet Marx Renoffski she becomes more enamored with him. One night Marx and his girlfriend get in a fight; the girlfriend tosses a bust of his head onto Margie’s lawn. She brings it inside the next morning and plays classical music for it, convincing herself that it is really listening to her. She kisses it. She is certain that Marx is the perfect man until he knocks on her door and invites himself inside. He presses himself against her, kissing her, but “he smelled of vomit, cheap wine, and bacon [and] needle-like hairs from his bear poked into her face.” (117) Page | 2 Disgusted at the faults that she didn’t imagine he had, she refuses his advances and kicks him out. Praying Mantis follows a man to a hotel where he is planning to his mistress. When he gets off the phone with her a younger woman in the room next to him knocks on his door and invites herself inside. She tells him about the praying mantis, how females bite the male’s head off during intercourse, and then she bites off his penis while giving him a blowjob. There is no apparent motivation behind her action; she gets up and leaves before he can even call an ambulance. Craft Paper In Hot Water Music, Charles Bukowski writes like he lives: fast, cheap and uncensored. His stories are both brutal challenges to the eastern literary establishment and existential character studies. They are as devoid of metaphors as they are of morality— at least, in a traditional sense. Whores, drunks, and small-time criminals find a home in these stories. Perhaps Bukowski’s stories also find a home in them. Bukowski made a conscious effort to push back against the styles of writing endorsed by mainstream literary journals, observing that “an intellectual says a simple thing in a hard way. An artist says a hard thing in a simple way.” His writing is plain, shallow, devoid of flowery imagery or complex symbolism. He says what he means and wastes no time in doing it. The exposition of his stories is sometimes only a sentence or two. “Harry and Landers” opens with four sentences that frame the context of the entire story, telling us that “[t]he phone rang. It was the writer, Paul. Paul was depressed. Paul was in Northridge.” Page | 3 He never uses metaphors, preferring instead to communicate a scene through concrete descriptions. He uses only three sentences in the opening paragraph of “Praying Mantis” to describe the main character’s room in the Angel View Hotel. “He walked inside and flipped on the light. A dozen roaches crawled away into the wallpaper and chewed and moved and chewed. There was a telephone, a pay phone.” Bukowksi’s descriptions are as boiled down and strained to arrive at only the most essential elements. He doesn’t allow imagery to get in the way of the narrative. Bukowski writes in vulgar, staccato sentences. They are as bare as the moral fiber of his characters. He draws much of his stylistic influence from John Fante, a pioneer of dirty realism. Bukowski’s condensed prose style and exploration of the L.A. slums are drawn from Fante’s semi-autobiographical Ask the Dust. The short, sharp-edged sound of his prose mirrors the violent and depraved themes that his stories. In “Praying Mantis” he writes about a man whose penis is bitten off during fellatio. His jagged sentences give the language itself a feel that complements the event: “…suddenly she bit into his cock, hard. She almost bit him in half. Then still biting she yanked her head up. A piece of the head came off. Mary screamed and rolled over on the bed. The blonde stood up and spit. Pieces of flesh and blood spattered on the rug.” Bukowski’s work displays elements of postmodern fiction. His stories are rife with irony and black humor, and the characters as well as the dialogue are often tonguein-cheek. His description of the poet Victor Valoff in Scum Grief offers a sarcastic take on pretentious artists: “Some piece of wisdom would be inscribed on [his artwork] like: Page | 4 Green heaven come home to me I weep grey, gray, grey, gray… Valoff was intelligent. He knew there were two ways to spell grey.” His tone is vulgar and jaded; his stories read more like bowel movements than narratives. He writes honestly and critically, admitting in the autobiographical story “How to Get Published” that he is “a complete asshole and horrible human being.” Thomas R. Edwards claims in the New York Review of Books that Bukowski “writes as a degenerate lowbrow contemptuous of our claims to superior being.” Despite their vulgarity, Bukowski’s stories deal with themes that are relatable, deep and plaintive struggles that are an inevitable part of the human condition. Beer at the Corner Bar explores selfishness and apathy. The protagonist goes out to a bar and is interrogated by another curious customer. When asked about a fire that killed fifty orphan girls, he gives a disinterested response, explaining, “If I had been there I suppose I would have had nightmares about it for the rest of my life. But it’s different when you just read about it in the newspapers.” Bukowski crafts a pessimistic picture of the world through the lens of his despicable, narcissistic characters with his own searing brand of honesty. Hot Water Music is saturated with Bukowski’s own voice. His stories are driven by a heavy-handed cynicism that made him famous in literary circles. In The Great Poet, a writer visits a famous poet who “had taught at many universities” and “had won all the prizes, including the Nobel Prize”, only to discover that he is actually a slob, a pervert, the antithesis of fine art. “The smell of vomit, wine, urine, shit and decaying food was in Page | 5 the air. I began to gag. I ran to the bathroom, vomited, and then came out.” Bukowski despised pretentiousness and, perhaps, put vulgarity on a pedestal. His characters are disillusioned, lonely, and marginalized by society. Almost all of his protagonists are antiheroes. He draws on his own experiences for most of his stories, often writing about his fictional counterpart, Henry Chinaski. The men in his stories are violent, vulgar alcoholics. Hot Water Music explores an array of unfortunate characters: struggling artists, alcoholics, and sexual deviants occupy his brutally concise narratives. The protagonists in “The Man Who Loved Elevators,” “Turkeyneck Morning,” and “The Worst Hangover Ever”, for instance, are all rapists. Bukowski doesn’t portray them with any more disdain than he directs at his other characters. He is even-handed with his hatred, and random acts of violence, he seems to suggest, are an inevitable facet of human nature. His stories are grounded in a gritty kind of realism that transcends the narrative and threatens to pop out of the page and beat the reader over the head with a fifteendollar handle of Popov. His fiction is set in shoddy apartments with leaking sinks and mildewed carpets, on creaking barstools, in the streets of the city he knew better than any other— L.A. Bukowski often communicates place indirectly, framing his stories in social or economic settings. In “The Man Who Loved Elevators” he writes that the protagonist’s “job was getting to him. Six years and he didn’t have a dime in the bank. That’s how they hooked you— they never gave you enough so you could finally escape.” The hopelessness conveyed in this sentiment develops the emotional setting of the story, a device that appears more than once in this story collection. In “Head Job”, for example, Page | 6 Bukowski describes a widow’s disillusionment with relationships: “men seemed to lack magic, most of them were bad lovers, sexually and spiritually.” He leverages the feelings of his characters into larger moods that frame the context of each story in Hot Water Music. A fair criticism of Bukowski’s writing is its rigidity; his characters are predictable, his themes of violence and hopelessness universal in his stories. It is also fair to point out that his situations and characters, while similar, build on each other throughout Hot Water Music and leave the reader with a dishearteningly wholesome view of what it is to be drunk, poor, and out of luck in Los Angeles. Charles Bukowski is a ubiquitous figure among American authors. He is remembered just as much for his uncompromising dirty realism as his lifestyle, one not far removed from those of the characters occupying his fiction. His direct and concise prose inspired an entire generation of fiction writers, journalists, and poets, but it was his frank portrayal of American lowlife that set him apart from his contemporaries and earned him status as ‘the poet laureate of skid row’. Through his controversial writing he cultivaed a reputation of mythological proportions and became a sort of fictional character himself, a folk hero among heathens immortalized for his vulgar cynicism. Page | 7