A HISTORY OF ACCOUNTING AT LSE

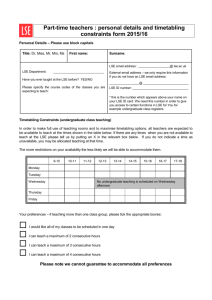

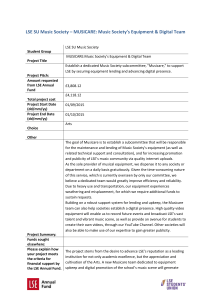

advertisement