Q&A on Canal Irrigation in Plain English

advertisement

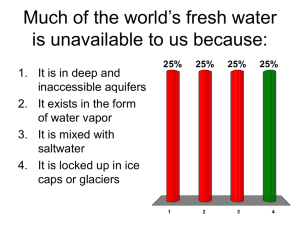

Q&A of Canal Irrigation in Plain English 1. How does canal irrigation differ from groundwater irrigation? Canal Irrigation differs from groundwater irrigation, because it delivers water collected in an external watershed to the irrigation command. This, within the nature of randomness, is finite. When the dam is empty, there’s no more water to deliver. Groundwater irrigation, on the other hand, uses water stored in the aquifer below the command area. In the event when groundwater pumping exceeds recharge, groundwater irrigation will result in groundwater decline, an unsustainable outcome. Farmers dig deep to get more and more, until it becomes uneconomical to do so. Hence comparison of irrigation from these two distinctively different resources is like comparing apples with oranges. Not a wise thing to do. 2. What is the role of Groundwater in Canal Commands? In almost all canal commands, groundwater levels have risen due to canal irrigation, and have caused waterlogging. In areas where groundwater is saline, salinity has become a problem too. Groundwater pumping in fresh water aquifers has alleviated water logging, and facilitated recycling of leached canal water. This is a wide phenomenon in Punjab and Haryana in India and in Pakistani Punjab. Estimated groundwater decline in these states is only between 20 to 50 cm pa, although in some parts of the canal command, all the irrigation requirement was met by groundwater pumping. Water balance calculations for rice-wheat rotation in Sangrur, Punjab shows that approximately 400 mm is provided by canal irrigation and 125 mm is provided by groundwater, although farmers report that they do not receive canal water. In summary, groundwater pumps have increased reliability of water supply, alleviated waterlogging, facilitated recycling of canal water and supporting increase in cropping intensity in many canal commands. However, the % of net groundwater used in these canal commands as a part of the total water budget is small, and inadequate to substitute canal water. 3. Why do we have water scarcity in canal commands? Scarcity occurs when demand is higher than the supply. Since the 60’s, cropping intensity in all canal commands has increased to meet the demand for food. IBIS, originally designed for 70% cropping intensity, now supports 170% cropping intensity. Water available in dams is inadequate to meet this demand. Furthermore, in some instances, canal geometry is inadequate to carry water, even if it is temporarily available, resulting water shortage at tail ends. If groundwater is fresh and suitable for irrigation, groundwater well are in use. 4. Why do we have in-equity within canal commands? The need to maximize crop production and lenient enforcement of water rights had permitted head end farmers to use water as much as they need. This in conjunction with scarce water supply and inadequate canal capacities have resulted in inequity. This is case where a policy addressing a macro issue (food security), has taken precedence over a policy addressing a micro issue (equity in water delivery). 5. How does storage influences canal irrigation management? With respect to storage of water upstream for canal irrigation, there are following three possibilities, and the degree of control which the irrigation systems managers could have, will vary depending on the extent of storage, compared to annual diversions from the river. a) No significant storage – In Nepal’s Terai, there are hardly any reservoirs storing water. Irrigation canals divert water from the river to irrigation areas. So, in non-perennial rivers, water supply in dry years is limited. b) Storage is less than annual diversions- In the IBIS of Pakistan, storage is approximately 10% of the annual flow. Hence the Pakistanis divert water to far distances to avoid water draining into the sea. They have very limited control. c) Storage is more than the annual flow- In the MDB of Australia, storage is 4 times that of the annual flow. This helps them with many sophisticated management interventions, including water markets. A farmer could sell his irrigation water on an annual basis, before the irrigation season starts, to another farmer. The buyer in this case will have secure water supplies. There are cases of permanent trade too. 6. Why is regular maintenance of irrigation canals necessary? Canal irrigation systems distribute water due to gravity. For example, Bhakra dam stores water at an elevation of 396 m amsl at base, and stores 225 m of water column, resulting in a total gravity head of 620 m. It irrigates areas in Punjab and Haryana at elevations ranging from 200 – 250 m amsl, approximately 100 to 150 km away. Water stored at zero velocity in the dam, ends up in the farmers field at zero velocity. In other words, velocity head is zero at both ends. A hydraulic head of about 370 m is lost between the dam and the field. This head is converted into velocity head, which transports the water from the dam to the field and overcomes friction in the canal. This dissipating energy moves sediment and deforms canal geometry. Velocities are high in primary canals, which are therefore, subject to deformation and detachment of fine soil particles, more than secondary and tertiary canals. Sediments settle when velocity of water is low. This happens in the secondary and tertiary channels. Hence, sedimentation and deformation of canals are inevitable, requiring regular maintenance. If not, canals will not be able to deliver water as per the design. 7. Are canals designed for specific crops? There seems to be a misunderstanding that design of canal irrigation is crop specific. Often it is stated that canals were designed to irrigate specific crops such as rice, which is incorrect. This stems from one’s misconception of what irrigation is. Irrigation is transferring storage of water from its source, (dam or aquifer) into the root-zone. Crop uptakes the water, when available in the root-zone, depending on atmospheric conditions and crop characteristics. So, any crop can be grown in a irrigated canal command. 8. Is it possible to introduce pressurized irrigation methods in canal commands? Canals deliver water due to gravity, and therefore no major investments is required to practice gravity based irrigation methods, such as flood irrigation or furrow irrigation. However, if a farmer wishes to convert his irrigation method from gravity irrigation to pressurized irrigation, then, storage becomes necessary. Storage may occur in the canals, or in the farm ponds. On rare occasions, pipes are connected to dams to take advantage of the gravitational head in the dam. Change to the pressurized irrigation method will give better control of water and minimize conveyance losses, assuming there is water available in the canal. 9. How flexible can irrigation timing be? A typical root zone of 1 m depth, can store at least 400 mm of water, and about 300 mm is extractable by roots. Hence an initially saturated root zone could meet evaporation needs for a month or more. But in most cases, water is inadequate to saturate the root zone, so frequent irrigation is necessary. 10. Who manage canal irrigation systems? Several agencies are involved in canal management in Asia. For example, in Pakistan, Indus River Statutory Authority, IRSA, is responsible for allocation of water among the states. Water And Power Development Authority is responsible for dams, link canals and barrages. State Irrigation Departments are responsible for maintenance of primary and secondary canals, WUAs are responsible for the management of tertiary canals (this is where most sedimentation occurs – velocities are near zero), Revenue Department is responsible for collection if Irrigation Service fees, Planning Commission is responsible for prioritizing and allocation of funds for O&M of irrigation canals, and Agriculture Department advises farmers on on-farm water management. An attempt to bring state level agencies under a single authority had very limited success in Pakistan