DOC - Center for Ocean Solutions

advertisement

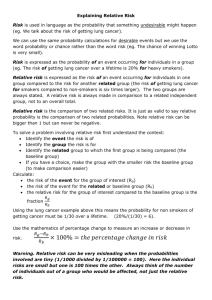

Mach, M.E., S.G. Reiter & L.H. Good. 2015. Managing a mess of cumulative effects: linking science and policy to create solutions. Current: The Journal of Marine Education 29(1):26-31 Slide Narrative for B. Law 101: Cumulative impacts Developed by Sarah M Reiter, February 2015 Center for Ocean Solutions Slide No. 1 2 Title Narrative Title Why look beneath the surface? 3 Searching for the disconnect Title slide, goals. The health of ecosystems is declining – in terrestrial and aquatic systems – and is largely attributed to the increasing number of human activities that are occurring. As discussed in the science presentation, where and when those activities overlap is also of concern because the cumulative effects of multiple stressors can have significant effects on the structure and functioning of ecosystems. Cumulative effects assessment (CEA) is a pervasive challenge across jurisdictions on both land and sea and despite legal requirements to analyze cumulative effects, they continue unabated. Research (by Prahler et al. 2014) identified disconnects between legal mandates and effective actions in an effort to bridge the gap between the legal requirements and the constraints associated with the real-world. For the next couple of minutes, I’ll be reviewing the three aspects of CEA that were identified as essential to bridging the gap between legal mandates and effective action. When Prahler et al. 2014 reviewed the U.S. federal law, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and California state law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), and associated agency guidance, regulations, and case law, their legal team discovered that assessment (CEA) challenges arise due to ambiguous legal interpretations as well as a project based approach. This project-level approach is vastly different than the science approach, where the focus is at the impact level. Three aspects of the cumulative effects legal framework beg rethinking, by looking beyond the project to (1) account for impacts, (2) advocate for smart baselines, and (3) choose the right spatial scale. 4 Searching for the disconnect: Impacts Following a review of U.S. law, we will look beyond the US territorial waters to see whether these three aspects are common in other jurisdictions, such as New Zealand. We will explore New Zealand’s legal framework because this jurisdiction is particularly progressive in approaching coastal management. For each challenge we will be spending the next couple of minutes discussing the three aspects of CEA that beg rethinking by discussing (1) the law, (2) the reality, (3) the action needed to 1 Mach, M.E., S.G. Reiter & L.H. Good. 2015. Managing a mess of cumulative effects: linking science and policy to create solutions. Current: The Journal of Marine Education 29(1):26-31 5 Impacts: The Law 6 Impacts: The Interpretation 7 Impacts: The Action 8 Searching for the disconnect: Baseline 9 Baseline: The Law improve CEAs. We can start by examining Challenge 1: Accounting for impacts. Impacts from other projects are often insufficiently analyzed in review documents. Both federal and state (NEPA and CEQA) guidance generally allow agencies to capture the cumulative effects of past actions by describing the current aggregate effects of past actions, without discussing the details of individual past actions. Many agencies do go beyond this requirement by individually listing similar past, present, or future projects in their cumulative impact analyses; however, these lists are usually cursory and only focus on similar types of projects rather than all projects which may impact the habitat or species at issue. In addition, agencies using the list approach frequently fail to analyze the impacts of the listed projects, leading to a disconnect between the list and the analysis. However, these lists are usually cursory and only focus on similar types of projects rather than (1) all projects which may impact the habitat or species at issue over time, and (2) the impacts associated with those projects over time. To overcome this legally defensible barrier to achieving the legal intent of CEA, agencies can include lists of relevant effects from other past, current and future projects within review documents rather than only listing similar individual projects. One way to help agencies have easier access to this information is to invest in software for tracking and mapping permits and review documents to enable agencies and stakeholders to identify projects that may be relevant in cumulative impacts analyses. To overcome this legally defensible barrier to achieving the legal intent of CEA, agencies can include lists of relevant effects from other past, current and future projects within review documents rather than only listing similar individual projects. One way to help agencies have easier access to this information is to invest in software for tracking and mapping permits and review documents to enable agencies and stakeholders to identify projects that may be relevant in cumulative impacts analyses. The second challenge, advocating for a smart baseline requires an understanding of the role that a particular reference point can play in altering the outcome of CEAs. Agencies often fail to adequately characterize the environmental baseline, which establishes reference points against which potential impacts are evaluated for significance. US and California law allow for agency discretion when it comes to determining baseline, so long as the agencies can justify their selection. Setting a proper baseline that includes consideration of 2 Mach, M.E., S.G. Reiter & L.H. Good. 2015. Managing a mess of cumulative effects: linking science and policy to create solutions. Current: The Journal of Marine Education 29(1):26-31 10 Baseline: The Interpretation 11 Baseline: The Action 12 Searching for the disconnect: Scale 13 Scale: The Law 14 Scale: The Interpretation 15 Scale: The Action past and future impacts is critical. By using a baseline of current environmental conditions, agencies can overlook prior impacts that were either unforeseen or greater in reality (either collectively or in isolation) than initial predicted. This can skew the significance determination for the proposed project and its alternatives and leads to an ever-shifting baseline, in which the effects of each new project become folded into the next project’s “existing conditions” baseline. Because the law allows for agency discretion, there is no incentive to select a smart baseline when an existing baseline will do. Selecting a baseline becomes a matter of choice, where despite discretion to do so, due to the extra legal and technical hurdles involved in using a baseline of past, pristine conditions, agencies are unlikely to choose a historic baseline without any policy changes. The norm is the existing conditions baseline. The momentum for this bright line rule is hard to overcome despite agency discretion to select a baseline of its’ choice so long as it can justify the choice. To overcome the matter of choice that results in use of the existing conditions baseline, the regulations should be amended to require agencies and project proponents consider historic data and trends even if using a baseline of existing conditions so that CIA better aligns with scientific principles. The third challenge, choosing the right spatial scale, requires an understanding of the role that spatial scale can play in altering the outcome of CEAs. Agencies have difficulty determining the appropriate geographic scale for analysis and regulatory requirements are often vague. Legal requirements do not clearly define the appropriate geographic scale of analysis though US and California law (NEPA and CEQA) embrace two general principles (1) geographic scale should be based on resource or system, and (2) courts will defer to agencies so long as the agencies support or justify their selection of geographic scale. Because the law approaches CEA from the perspective of a particular project and provides little clarity, agencies often choose a scale too small to account for CE such that global and regional features are not taken into account. A multi-scale approach to geographic scale allows for the entire system to be considered so that no interaction is too large or too small for the analysis. Choosing the right spatial scale requires a step by step process across spatial scales. Agencies should consider impacts on local, regional, and global geographic scales to ensure they do not overlook local impacts or ignore global 3 Mach, M.E., S.G. Reiter & L.H. Good. 2015. Managing a mess of cumulative effects: linking science and policy to create solutions. Current: The Journal of Marine Education 29(1):26-31 16 17 18 scale changes. Research (by Prahler et al. 2014) recommends the following steps for considering cumulative impacts across spatial scales: • Identify the biogeographic region: Emphasize regional level through development of watershed or regional scale plans and programmatic EIRs to address multiple sources of stressors at once, identify valuable environmental components and indicator species, establish ecological thresholds for agencies and project proponents to use in their site specific determinations • Define the impact zone: Because identifying all possible species, habitats, or communities impacted by the project would be cost and time intensive, agencies could limit their scope to identifying priority species of interest that would be impacted by the project. Focus on species and indicators: Because it is impossible to map every species independently, agencies should first focus on legally protected species and system health indicators (i.e., species or habitats known to vary with ecosystem health), where identified. • Understand the reason of impacts: Apply the key principles of ocean health: (1) species diversity, (2) habitat diversity, (3) Heterogeneity, (4) Key species, (5) Connectivity of species. Looking beyond U.S. We can look beyond U.S. territorial waters to see whether these waters three aspects are common in other jurisdictions, such as New Zealand. New Zealand is particularly progressive in approaching coastal management. While New Zealand experiences similar overarching challenges, progress is being made on a couple of fronts (1) acknowledging climate change drivers, and (2) implementing the language of the law on thresholds. Acknowledging The New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement (NZCPS) is a climate change national policy statement under the Resource Management Act drivers 1991 (‘the Act’). The purpose of the NZCPS is to state policies in order to achieve the purpose of the Act in relation to the coastal environment of New Zealand. New Zealand’s Coastal Policy Statement #3 calls for the adoption of the precautionary approach towards activities with unknown effects on the coastal environment, and towards coastal resources that are vulnerable to climate change. It acknowledges a relative lack of understanding about coastal processes in the face of climate change and the actual and potential effects of activities and developments on coastal processes. Implementing New Zealand’s Coastal Policy Statement #7 mandates regional thresholds CE management and implementation of thresholds “where practicable” to avoid CEs. For now, it is worth mentioning that 4 Mach, M.E., S.G. Reiter & L.H. Good. 2015. Managing a mess of cumulative effects: linking science and policy to create solutions. Current: The Journal of Marine Education 29(1):26-31 19 Moving from knowledge to action 20 Waypoints for Cumulative Effects 21 For further resources this idea of thresholds challenges us to think differently about CE and the vulnerability of ecosystems. Whenever you have a system response where a small change in one factor can lead to a disproportionately large change in the other, then you have the chance to detect a threshold and potentially take that threshold into account in your management. So now that we’ve looked beyond projects to explore how the law and interpretation of the law can move CEA forward in U.S. waters, and we’ve looked beyond U.S. waters to explore progress being made in other jurisdictions, I’d like to quickly review some waypoints forward. Barriers associated with these three challenges of CEA can be overcome by (1) considering all projects and their associated impacts, (2) accounting for historic data and trends, and (3) using a multi-scale approach. The following information provides a (1) link to teaching resources at the Center for Ocean Solutions, (2) citation for which most of this talk is based, (3) author contact information, (4) citation for which most of the images are based and (5) funding information. 5