Combatting Bullying in the Work place-Intended and

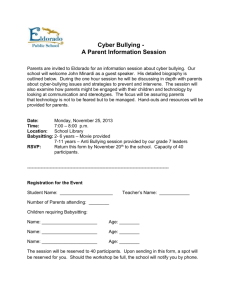

advertisement

UFHRD Abstract: S5-22 Combatting Bullying in the Work place: Intended and Implemented Policies Professor Maura Sheehan, (Maura.Sheehan@nuigalway.ie), National University of Ireland Galway. Dr TJ McCabe (Thomas.Mccabe@ncirl.ie), National College of Ireland, Dublin. 1 Abstract Combatting Bullying in the Work place: Intended and Implemented Policies Purpose Workplace Bullying is an ever-evolving organisational problem which is likely to be exacerbated in times of economic and organisational change (Salin, 2003; De Cuyper et al, 2009). Research in the UK suggests that within the public sector six out of ten workers had either been victim or witness to workplace bullying (ACAS, 2013). A National Survey of the work force in Ireland found that 6.2% of respondents had been exposed to frequent bullying over the previous 12 months (O’Moore et al., 2004). While there is no absolute consensus about how to define it, most organisations in Ireland define workplace bullying as: “Repeated inappropriate behaviour, direct or indirect, whether verbal, physical or otherwise, conducted by one or more persons against another or others, at the place of work and/or in the course of employment, which could reasonably be regarded as undermining the individual’s right to dignity at work” (p. 11, Report of the Expert Advisory Group on Workplace Bullying, 2005). In Ireland, as in many countries, the most common anti-bullying measure is formal ‘dignity at work’ policies and procedures within organisations. Yet, incidents of workplace bullying appear to be rising. Thus, the question remains as to why formal anti-bullying policies appear to lack effectiveness. 2 It has been an uphill battle for Human Resource Management (HRM) and Human Resource Development (HRD) practitioners to establish the extent of workplace bullying. Colleagues not affected frequently write off victims of workplace bullying as being ‘oversensitive’ or ‘lacking backbone’. It is also often extremely difficult for victims of bullying to prove they are being bullied. Covert bullying may involve withholding information, constant criticism and belittling of the victim’s performance, snide and derogatory comments. Covert bullying will often not happen every day but the victim never knows when or where the bully will ‘strike’ which further adds to their victimisation. Victims will often ‘slip away’ in silence by leaving their current employer. A common theme that links the bully and the victim with respect to workplace bullying is that of organisational ‘culture’. There is strong evidence that organisations can develop cultures whereby workplace bullying is effectively condoned or even rewarded. This, in turn, is linked to what has been termed ‘destructive leadership’ whereby managers contribute to the prevalence of bullying in organisations through non-intervention. Indeed, research shows that the highest incidences of workplace bullying are found where senior management are perceived as tolerating/ignoring such behaviour and allowing such a culture to fester. Formal policies are unlikely to be effective in organisations with a bullying culture. Within the Irish public healthcare system, bullying in the workplace should be addressed through the ‘Dignity at Work Policy of the Health Service Executive’ that came into operation on 1 May 2004. Yet academic and practitioner evidence suggests that nurses and midwives working in Ireland continue to experience workplace bullying (McMahon, et al., 2013). The intensification of work and reduction of resources within the Health Service Executive (HSE) in post-crisis 3 Ireland appears to have exacerbated bullying. Bullying has been found to have very negative consequences for nurses/midwives’ personal health, personal and family relationships and adds to already high levels of stress experienced by nurses/midwives working within the Irish health care system. Research also shows that victims of bullying often have difficulty performing at work and in health care there could have very negative implications for the wellbeing and safety of patients (McMahon, et al., 2013). Design/methodology/approach The study initially involved a focus group examining the experiences of overseas trained nurses on perceived and actual incidents of bullying and discrimination. The participants were taken from both the acute and community sector. They were randomly chosen through a process of purposive sampling, reflecting variations in country of origin, age, grade, ward and tenure. A grounded theory approach was used to analyse the qualitative focus group data. The next phase of our investigation involved the use of a survey to explore and measure perceived and actual incidents of workplace bullying and discrimination amongst overseas and national nurses. The survey examined the links between actual and perceived bullying and discrimination with organisational performance, productivity, workplace absenteeism, turnover and other mediated variables such as commitment and stress. It also looked at how bullying could be reduced and the supports required by those who experience bullying in a nursing, healthcare context. Findings 4 Despite a growing recognition of the importance of the implementation rather than simply the presence of HR practices, a significant empirical gap remains in examining implementation processes and assessing whether implementation is associated with the intended objective being achieved (see Woodrow and Guest, 2013 for a notable exception in the context of workplace bullying). The aim of this article therefore is to examine the process anti-bullying policy implementation, including the role of training and development, and its relationship with employee responses. This is achieved through analysis of a large survey (n = 2,400) that focussed on the presence and implementation of workplace bullying policies among nurses and midwives in Ireland, the majority of whom are members of the Irish Nurses and Midwives Organisation (INMO). Whether the presence and implementation of workplace bullying policies is associated with a reduced probability and intensity of workplace bullying is examined. The analysis of implementation is extended further by examining the perceived effectiveness of support policies recommended to, and utilised by, employees who report work place bullying. This research draws on a conceptual model of effective implementation of HR practices developed by Guest and BosNehles (2013). The theoretical framework that will be tested is outlined in Figure 1. Themes emerging from our initial focus group discussion were as follows. Many overseas trained nurses or those on precarious work contracts received significantly higher work-loads and were called upon to do tasks that national nurses were unwilling to do. Inconsistency in the application of hospital rules, policies and procedures also emerged as a theme during the focus group discussion. Many participants discussed perceived favouritism and bias in the treatment of overseas trained nurses and national nursing staff. A good example of this concerned the application of hospital rules, policies and procedures which they felt were applied mainly towards 5 overseas trained nurses. The participants felt that the ‘duty of care’ in relation to the well-being and welfare of overseas trained nurses was not taken seriously by hospital management. They also discussed restricted access to professional training and development as well as promotion to leadership and managerial roles amongst overseas trained nurses. Research limitations/implications The qualitative and quantitative findings of our study will inform the construction of a conceptual model illustrating the various HRD challenges drawn from the experiences of bullying amongst overseas and national working in the Irish health service. Practical implications Our findings offer health service managers and practitioners useful insight and guidance in successfully dealing and managing instances of workplace bullying. The findings of our research will provide guidance to health service managers and practitioners in building positive and healthy workplace cultures, built on mutual understanding and respect. Social implications Our findings will help ensure that workplace bullying is effectively managed within health care and similar professional organisations, with positive health and social outcomes for all those concerned. Originality/value 6 Our study aims to build on the findings of other studies on the subject of workplace bullying within health care and similar professional organisations. Key Words: Nurses, Bullying, Discrimination, Health Service, Survey, Focus Group. 7 Figure 1. Conceptual Model Policy Implementation: Policy Awareness Perceived Quality of Policy Intended Policy: Bullying: Presence of antibullying Policy Probability Intensity Policy Implementation: Promotion (“passive” & “active”) of anti-bullying Policies 8 References Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) 2011 Unison Survey of UK Public Sector Workers. Cited from: http://www.acas.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=3861 [Accessed 4 April 2015]. De Cuyper, N., Baillien, E. & De White, H. (2009) Job insecurity, perceived employability and targets’ and perpetrators’ experiences of workplace bullying. Work & Stress. 23(3): 206-224. Guest, D. and Bos-Nehles, A. (2013) HRM and performance: the role of effective implementation. In J. Paauwe, D. Guest and P. Wright (eds.), HRM and Performance: Achievements and Challenges. Chichester: Wiley. McMahon, J., MacCurtain, S., O’Sullivan, M., Murphy, C. & Turner, T. (2013) A Report on the extent of bullying and negative workplace behaviours affecting Irish nurses. Dublin: Irish Nurses and Midwives Organisation (INMO). O'Moore, M., Lynch, J., & Daéid, N. N. (2003) The rates and relative risks of workplace bullying in Ireland, a country of high economic growth. International Journal of Management and Decision Making. 4: 82−95. Report of the Expert Advisory Group on Workplace Bullying (2005). [Online]. Available from: http://www.djei.ie/employment/osh/bullying.htm [Accessed 1 April 2015]. Salin, D. (2003) Ways of explaining workplace bullying: A review of enabling, motivating and participating structures and processes in the work environment. Human Relations. 56: 12131232. 9 Woodrow, C. and Guest, D. (2013) When good HR gets bad results: exploring the challenge of HR implementation in the case of workplace bullying. Human Resource Management Journal. 24(4): 38-56. 10