Boss Tweed Historical Overview WKSHT

advertisement

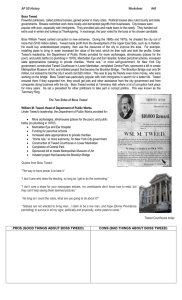

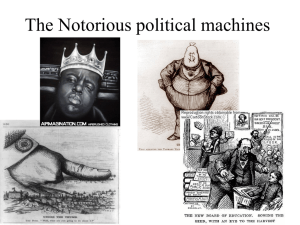

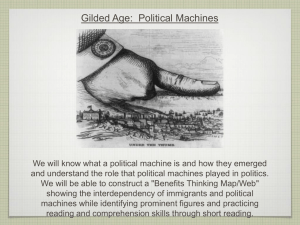

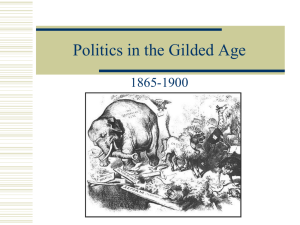

Name: ______________________ Date: ________ Mr. Armstrong SS8 | AIM #: ___ Boss Tweed & Political Corruption Historical Overview To many late 19th century Americans, he personified public corruption. In the late 1860s, William M. Tweed was the political boss of New York City. His headquarters, located on East 14th Street, was known as Tammany Hall. He wore a diamond, orchestrated elections, controlled the city's mayor, and rewarded political supporters. His primary source of funds came from the bribes and kickbacks that he demanded in exchange for city contracts. The most notorious example of urban corruption was the construction of the New York County Courthouse, begun in 1861 on the site of a former almshouse. Officially, the city wound up spending nearly $13 million-roughly $178 million in today's dollars--on a building that should have cost several times less. Its construction cost nearly twice as much as the purchase of Alaska in 1867. The corruption was breathtaking in its breadth and baldness. A carpenter was paid $360,751 (roughly $4.9 million today) for one month's labor in a building with very little woodwork. A furniture contractor received $179,729 ($2.5 million) for three tables and 40 chairs. And the plasterer, a Tammany functionary, Andrew J. Garvey, got $133,187 ($1.82 million) for two days' work; his business acumen earned him the sobriquet "The Prince of Plasterers." Tweed personally profited from a financial interest in a Massachusetts quarry that provided the courthouse's marble. When a committee investigated why it took so long to build the courthouse, it spent $7,718 ($105,000) to print its report. The printing company was owned by Tweed. In July 1871, two low-level city officials with a grudge against the Tweed Ring provided The New York Times with reams of documentation that detailed the corruption at the courthouse and other city projects. The newspaper published a string of articles. Those articles, coupled with the political cartoons of Thomas Nast inHarper's Weekly, created a national outcry, and soon Tweed and many of his cronies were facing criminal charges and political oblivion. Tweed died in prison in 1878. The Tweed courthouse was not completed until 1880, two decades after ground was broken. By then, the courthouse had become a symbol of public corruption. "The whole atmosphere is corrupt," said a reformer from the time. "You look up at its ceilings and find gaudy decorations; you wonder which is the greatest, the vulgarity or the corruptness of the place." Boss-rule, machine politics, payoff and graft, and the spoils system outraged late 19th century reformers. But were bosses and political machines as corrupt as their critics charged? George Washington Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, New York's Democratic political machine, distinguished between "honest" and "dishonest" graft. Dishonest graft involved payoffs for protecting gambling and prostitution. Honest graft might Your Notes, Analysis, Insights, etc. involve buying up land scheduled for purchase by government. As Plunkitt said, "I seen my opportunities and I took 'em." Paradoxically, a political machine often created benefits for the city. Many machines professionalized urban police forces and instituted the first housing regulations. Political bosses served the welfare needs of immigrants. They offered jobs, food, fuel, and clothing to the new immigrants and the destitute poor. Political machines also served as a ladder of social mobility for ethnic groups blocked from other means of rising in society. In The Shame of the Cities, the muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens argued that it was greedy businessmen who kept the political machines functioning. It was their hunger for government contracts, franchises, charters, and special privileges, he believed, that corrupted urban politics. At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, urban reformers would seek to redeem the city through beautification campaigns, city planning, rationalization of city government, and increases in city services. Essential Question: How do you interpret this political cartoon as it pertains to Boss Tweed? How might you explain this cartoon to someone who doesn’t know anything about the man?