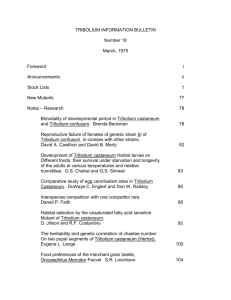

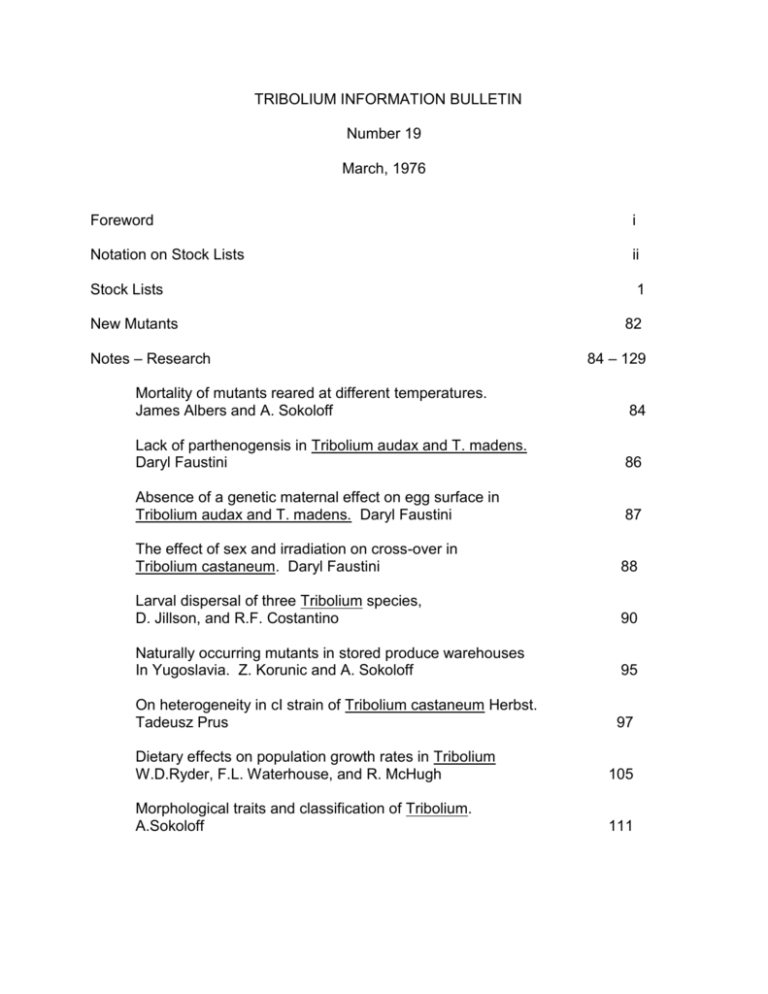

TIB_19 - spiru.cgahr.ksu.edu

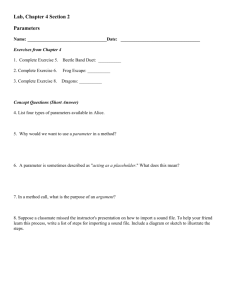

advertisement