Bannockburn and Independence

advertisement

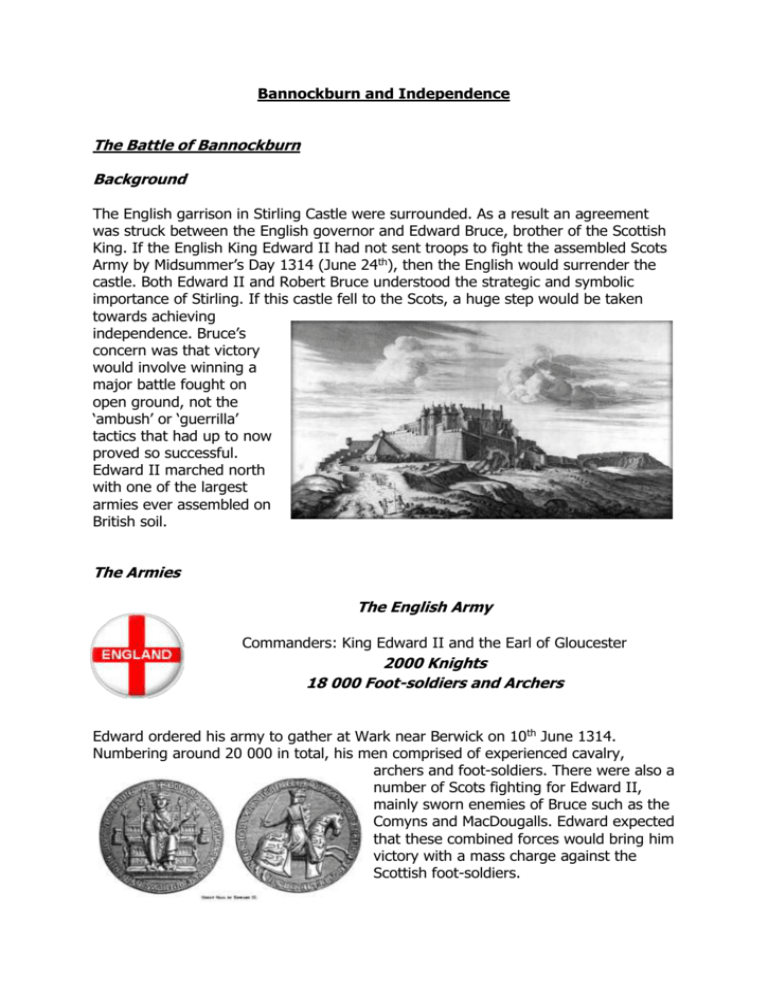

Bannockburn and Independence The Battle of Bannockburn Background The English garrison in Stirling Castle were surrounded. As a result an agreement was struck between the English governor and Edward Bruce, brother of the Scottish King. If the English King Edward II had not sent troops to fight the assembled Scots Army by Midsummer’s Day 1314 (June 24th), then the English would surrender the castle. Both Edward II and Robert Bruce understood the strategic and symbolic importance of Stirling. If this castle fell to the Scots, a huge step would be taken towards achieving independence. Bruce’s concern was that victory would involve winning a major battle fought on open ground, not the ‘ambush’ or ‘guerrilla’ tactics that had up to now proved so successful. Edward II marched north with one of the largest armies ever assembled on British soil. The Armies The English Army Commanders: King Edward II and the Earl of Gloucester 2000 Knights 18 000 Foot-soldiers and Archers Edward ordered his army to gather at Wark near Berwick on 10th June 1314. Numbering around 20 000 in total, his men comprised of experienced cavalry, archers and foot-soldiers. There were also a number of Scots fighting for Edward II, mainly sworn enemies of Bruce such as the Comyns and MacDougalls. Edward expected that these combined forces would bring him victory with a mass charge against the Scottish foot-soldiers. The Scottish Army Commanders: King Robert, Edward Bruce, James Douglas, Robert Keith and the Earl of Moray, Thomas Randolph 500 Knights 4500 Foot-soldiers and Archers As well as a small number of archers from the Ettrick Forest in the Borders, Bruce’s men were organised into four divisions of foot-soldiers and one of cavalry. Each division was divided into three or four schiltrons of spearmen. In reserve were approximately 2000 ‘small folk ’ – farmers and townspeople King Robert gathered his army around him at an area called the ‘Borestone’. There he raised the royal standard (flag). Bruce’s only chance of victory depended on forcing the English to fight on the marshy ground, just north of the Bannock Burn. This soft ground would make it difficult for the English cavalry to charge the smaller Scottish force. The problem was how to get the English army to move into this area. The English army would be arriving from the South along an old Roman road from Falkirk. Bruce needed to divert this army onto softer ground so set a number of traps to give the impression that the road to Stirling was ‘booby-trapped’ along its whole length. Large pits were dug on the road and these had the desired effect. The English commanders made the decision to leave the road and took up position near to the Carse and the Bannock Burn. Despite moving into the area that Bruce had hoped, remember that the English forces vastly outnumbered the Scots, both in terms of cavalry and infantry. The Scots may have had some advantages, however. The English Army had been on the march for weeks and exhaustion may have been starting to take its toll. The weather over these weeks had been extremely hot, adding to their discomfort. Furthermore, these troops had never fought together as a combined force and some were relatively untrained. A Personal Duel Just before the battle began on the 23rd June, an event took place that could have had dramatic consequences on the entire outcome. An English knight, Sir Henry de Bohun spotted King Robert and decided to take him on in single combat. Dressed in full armour he charged the Scottish King. Bruce, not yet dressed for battle dodged the attack and brought his battle axe down on de Bohun’s head, smashing through helmet and skull. The king is said to have remarked “Alas, I have broken my good battle-axe”. This incident served as a positive omen for the Scots. They were now even more convinced that God favoured a Scots victory. Other action on this day included a Scottish force driving off an attempt by English cavalry to free the surrounded troops at Stirling Castle. By the evening of the first day, the English were resting on land between the Bannock Burn and the Pelstream, another tributary of the River Forth. Boosted by leaked news of low morale among the English troops, the Scots now realised that their enemies were in a very confined space and, despite having fewer men, Bruce decided to attack early the next morning – Midsummer’s Day. The Key Events Although Bannockburn was actually fought over two days, most of the key events took place on 24th June. The English army outnumbered the Scots but did not behave like a cohesive fighting force. Perhaps too many of the English knights were interested in personal glory and were less concerned with what happened to those around them. Bruce’s men, though considerable fewer in number, were well drilled in the use of pole-arms, long spiked poles held outwards to form a schiltron. Bruce had taken up position on a low hill from which he could observe the entire English army. The Scots army knelt in prayer to which Edward II responded “Ha! They kneel for mercy.” Edward had miscalculated the mood of the enemy. As soon as the Scots heard the trumpets of the English army, they rose and formed into their schiltrons. The English troops began to attack but quickly realised that a series of new traps had been set by Bruce and his men. More pits had been dug between the English army and the schiltrons. Caltrops (iron spikes) had been scattered in front of the schiltrons to cripple the English horses. Again and again the English army found it could not break down the Scottish defences. Edward had clearly underestimated the challenges he would face and had not, for example, used his archers as effectively as his father had in defeating Wallace at Falkirk. When he realised this mistake, it was too late. A charge by the small Scots cavalry under Sir Robert Keith stopped the English archers firing on the schiltrons. By this stage a combination of the marshy ground, the fallen dead and wounded and riderless and crippled horses were hampering further English attempts to get at the Scottish troops. At this crucial moment, Bruce gave the order for his men to attack, marching in organised lines. At the same moment, another Scots army seemed to appear, rushing down a nearby hillside. In fact, this was not an army but another surprise organised by Bruce, a collection of servants, aides and ordinary civilians known as the ‘small folk’, organised to give the impression of reinforcement troops to intimidate the English. The plan worked, creating confusion and panic in the English ranks. Victory at Bannockburn The English army turned and fled from the battlefield. Edward II made his way to Stirling Castle where he was refused entry and was forced to make his way to Dunbar where a boat took him back to England. Many of the fleeing English soldiers drowned in the Bannock Burn or were captured. Around 30 years after the battle an English chronicler wrote: When both armies engaged each other and the great horses of the English charged the pikes of the Scots like into a dense forest, there arose a terrible crash of spears broken and horses wounded to death. The English in the rear could not reach the Scots because the leading divisions were in the way. There was nothing for it but to flee … the Earl of Gloucester, Sir John Comyn, and many nobles were killed besides foot-soldiers who fell in great numbers. The English had crossed the Bannockburn, now they had to re-cross it. In confusion many fell into it and many were never able to get out of it. The King and others fled. Some who were not so speedy were killed by the Scots who hotly pursued them. This had been an astonishing victory for the Scots. As well as the military success, they also captured much treasure, to an estimated value of £200 000 (or £50 million in today’s money). Bruce used some of this money and many of the captured prisoners to exchange for his wife and daughter. Success at Bannockburn effectively ended the English presence in Scotland and allowed Bruce and others to truly regard him as ‘Robert I, King of Scotland’. Edward II’s reputation was destroyed. He had lost a battle that the English should have comfortably won, given their numerical advantage. His army had been badly positioned and had been drawn into the traps and ploys set by the Scots. Overconfidence had caused him to fail to use his archers effectively and his army had been too quick to panic as the Scots pushed forward. It is also fair to argue that the Scottish army enjoyed certain advantages. They were well led by King Robert, Edward Bruce, the Earl of Moray and Robert Keith. The troops fought well as a unit and were dedicated to their cause of freeing Scotland from English rule. This motivation for why they fought may have played a hige part in their success. For many of the Scots their lives depended on victory in this battle. Their loyalty to the cause and to King Robert was solid. Bruce had inspired this loyalty and confidence in the years leading up to Bannockburn through tackling his Scottish enemies and gradually reducing the English presence. After Bannockburn Although the Scots had won at Bannockburn Edward II refused to accept that Bruce was king of Scotland. In an attempt to force his hand and acknowledge that Scotland was a separate country again, Bruce used his army to attack many towns in northern England. He recaptured Berwick and led raids that reached as far as York. Buildings were burned, property seized, people and animals killed. To place even more pressure on the English king, 50 Scottish earls, barons and nobles sent a document to the new Pope in Rome. The Declaration of Arbroath discussed how Robert had led the Scots to victory in the long war against Edward I and his son, and how the nobles had rallied behind Robert in their fight for independence. Other arguments the Declaration made included: Scotland had been an independent kingdom for a long time It had had 113 kings of its own Edward I had been cruel tyrant who caused destruction and death Bruce had rescued his people from misery They asked the Pope to end Bruce’s excommunication from the Catholic Church, accept him as true King of Scots, and encourage Edward II to do the same. The document was written and sent in 1320 and within a few years, the Pope agreed to recognise Bruce as the rightful King of Scotland. Peace with England would take a few more years. Edward II had always struggled to gain himself the reputation of his father. He had been an unpopular figure among many English nobles even before his humiliating defeat at Bannockburn. In 1327 his own wife Isabella, conspired against him and he was arrested, starved and eventually tortured to death on her orders. Their 14-year-old son now became Edward III. The English concluded that the time was right to end the war with Scotland and a peace treaty, the Treaty of Edinburgh was signed on 17th March 1328 (this treaty is sometimes referred to as the Treaty of Northampton, after the location of the English Parliament who accepted it). The Treaty included terms such as: English Kings would not claim rights over Scotland and its people ‘There would be a true, final and perpetual peace between the Kings, their heirs and successor and their lands and subjects.’ Bruce’s heir, his 4-year-old son David, should have a marriage arranged with Joan, sister of Edward III. After 32 years of war Scotland and England were now at peace. Sadly, Bruce did not live much longer to enjoy it. Dying of leprosy on 7th June 1329, he was succeeded by his young son who became David II. Postscript As Bruce lay dying he had made his closest friend Sir James Douglas promise that his heart would be taken on a crusade to the Holy Land (Israel). Douglas attempted to fulfil this promise and whilst Bruce’s body was buried in Dunfermline Abbey, his heart was cut out and carried in a silver casket. However, Douglas’ crusade got no further than Spain where he was killed in battle and Bruce’s heart was eventually returned and buried in the grounds of Melrose Abbey. Nearly 500 years later, in 1818, some work was being done in Dunfermline Abbey. Bruce’s tomb had been destroyed and lost hundreds of years before. Workers unearthed a coffin in which a skeleton was discovered, chest cracked and dressed in royal robes. It was the remains of King Robert. The body was reburied but before doing so, a cast of the skull was made. This helped sculptors to make the statue of Bruce that stands at Bannockburn.