PhD Student Handbook 2015-6 - London School of Economics and

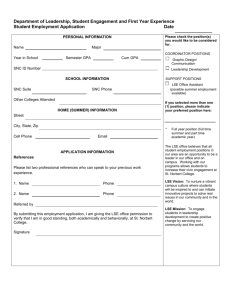

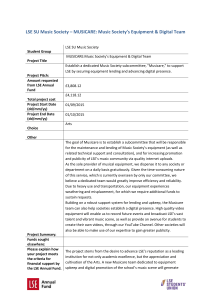

advertisement