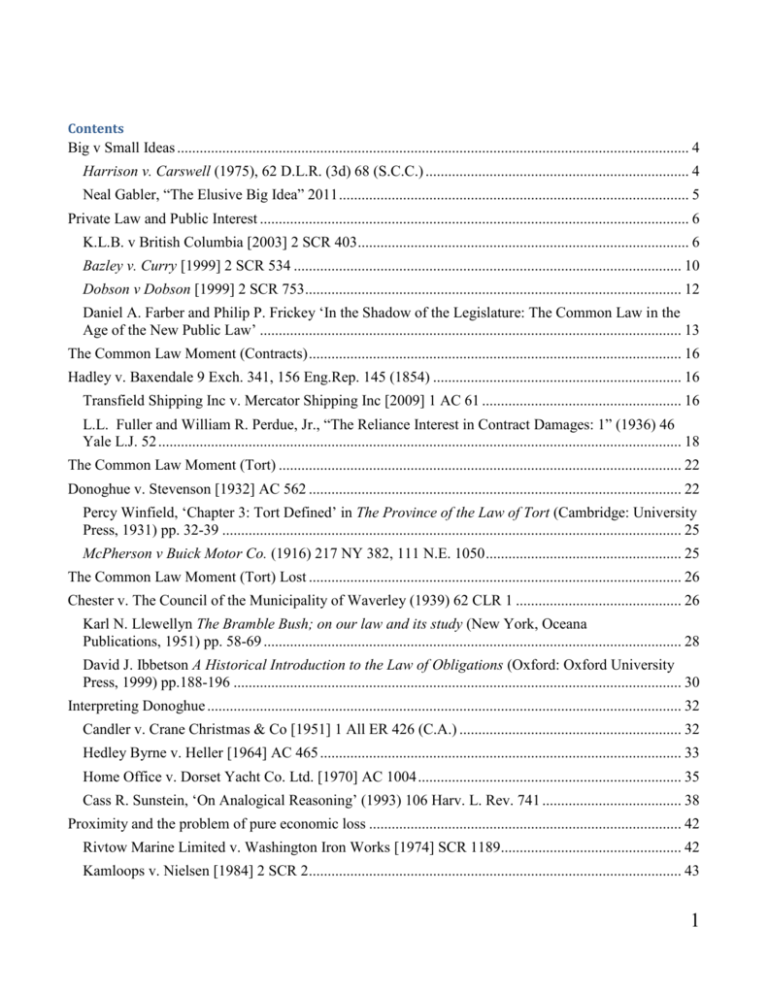

peels correctness

advertisement