Module A Elective 1 Sample Response: Mrs Dalloway and The

advertisement

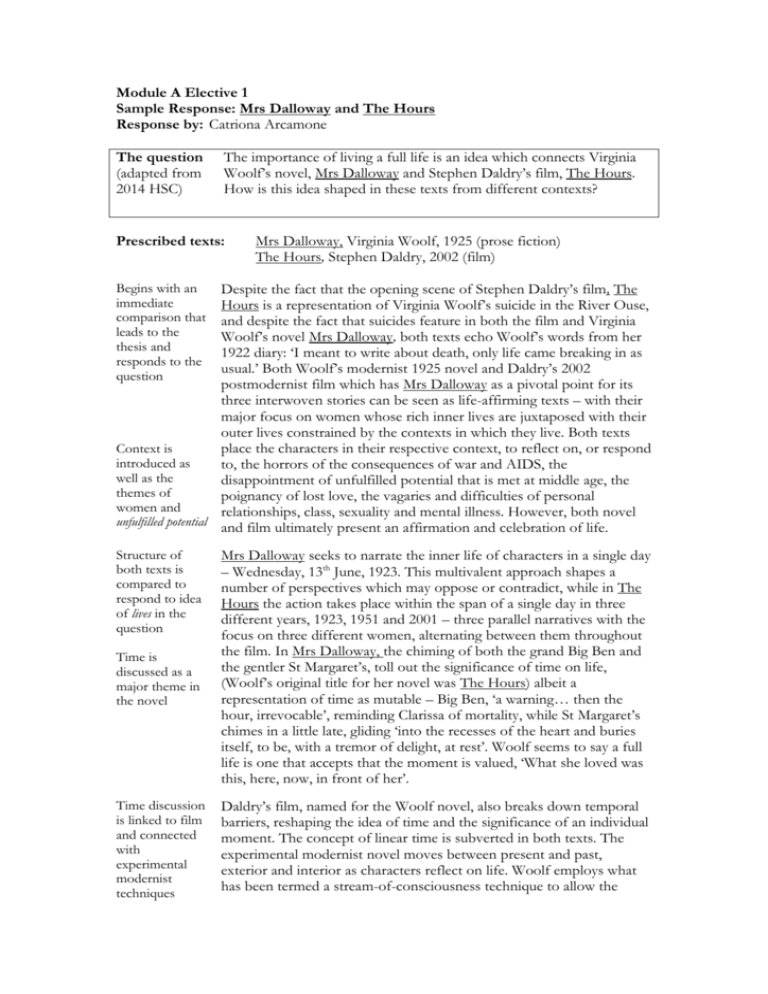

Module A Elective 1 Sample Response: Mrs Dalloway and The Hours Response by: Catriona Arcamone The question (adapted from 2014 HSC) The importance of living a full life is an idea which connects Virginia Woolf’s novel, Mrs Dalloway and Stephen Daldry’s film, The Hours. How is this idea shaped in these texts from different contexts? Prescribed texts: Mrs Dalloway, Virginia Woolf, 1925 (prose fiction) The Hours, Stephen Daldry, 2002 (film) Begins with an immediate comparison that leads to the thesis and responds to the question Despite the fact that the opening scene of Stephen Daldry’s film, The Hours is a representation of Virginia Woolf’s suicide in the River Ouse, and despite the fact that suicides feature in both the film and Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs Dalloway, both texts echo Woolf’s words from her 1922 diary: ‘I meant to write about death, only life came breaking in as usual.’ Both Woolf’s modernist 1925 novel and Daldry’s 2002 postmodernist film which has Mrs Dalloway as a pivotal point for its three interwoven stories can be seen as life-affirming texts – with their major focus on women whose rich inner lives are juxtaposed with their outer lives constrained by the contexts in which they live. Both texts place the characters in their respective context, to reflect on, or respond Context is introduced as to, the horrors of the consequences of war and AIDS, the well as the disappointment of unfulfilled potential that is met at middle age, the themes of poignancy of lost love, the vagaries and difficulties of personal women and relationships, class, sexuality and mental illness. However, both novel unfulfilled potential and film ultimately present an affirmation and celebration of life. Structure of both texts is compared to respond to idea of lives in the question Time is discussed as a major theme in the novel Time discussion is linked to film and connected with experimental modernist techniques Mrs Dalloway seeks to narrate the inner life of characters in a single day – Wednesday, 13th June, 1923. This multivalent approach shapes a number of perspectives which may oppose or contradict, while in The Hours the action takes place within the span of a single day in three different years, 1923, 1951 and 2001 – three parallel narratives with the focus on three different women, alternating between them throughout the film. In Mrs Dalloway, the chiming of both the grand Big Ben and the gentler St Margaret’s, toll out the significance of time on life, (Woolf’s original title for her novel was The Hours) albeit a representation of time as mutable – Big Ben, ‘a warning… then the hour, irrevocable’, reminding Clarissa of mortality, while St Margaret’s chimes in a little late, gliding ‘into the recesses of the heart and buries itself, to be, with a tremor of delight, at rest’. Woolf seems to say a full life is one that accepts that the moment is valued, ‘What she loved was this, here, now, in front of her’. Daldry’s film, named for the Woolf novel, also breaks down temporal barriers, reshaping the idea of time and the significance of an individual moment. The concept of linear time is subverted in both texts. The experimental modernist novel moves between present and past, exterior and interior as characters reflect on life. Woolf employs what has been termed a stream-of-consciousness technique to allow the reader to be privy to characters’ associative leaps in thought, while the film’s constant cutting between eras and characters explores the notion of lost moments, the connection between individuals and the value of life itself. The value of life – the act of being, of embracing life, is shaped in Mrs Dalloway through modernist techniques and reshaped in the postmodern approach of The Hours. The idea of context and women is introduced in the book Each text crosses different social, cultural and historical contexts, yet there are shared values and attitudes towards a number of issues. Woolf’s eponymous, middle-aged protagonist, placed firmly in the upper-middle-class of a post-World War I England suffers from a sense of malaise as she reflects on her role as ‘Mrs Richard Dalloway’ – her individual identity at times denied to her. The focus on the party she will give allows her to ruminate on one’s position as woman in the social hierarchy – and indeed we see a range of women whose position is compromised by the strictures of London in 1923. Clarissa and these minor characters provide great insight into the lives of women of the period, who despite their failings, still embrace those small things which are life. Women and context discussion focuses on the film showing how filmic techniques enhance the themes The three female protagonists of The Hours represent changing positions of women over time, this opposition represented by the different palettes used for each character which also work simultaneously to provide echoes from scene to scene. Philip Glass’s music, an integral presence, is also used to provide a counterpoint. Virginia Woolf is portrayed as privileged, but uncomfortable when dealing with servants, and in some ways subordinate to her husband Leonard. Laura Brown is unfulfilled and unhappy in her role as dutiful 1950s middle-class housebound mother and wife, caring for the ‘deserving’ returned service-man from World War II. While Clarissa Vaughan appears as a successful publisher, with freedom to make choices, she is seen to have an ambivalent position in upper-middleclass New York society, still in a sacrificial, sublimating role at the beginning of the 21st century. All four of the main female characters are frustrated by social expectations; although personal freedom and rights increased over the decades, domestic responsibilities of women and their resulting guilt remained for many a significant aspect of life. There is a movement between the two texts constantly contrasting the ideas The discussion on women moves to their relationships with others and retruns to the question on life Both texts explore the suppression and sacrifices of the individual to adhere to social requirements – women as carers, subservient to men, forced into living lives comprised of minutiae, ‘silenced ... and overshadowed by the heroics of men’. Laura Brown’s act reading of Mrs Dalloway, stitched together with Virginia’s writing of the novel, parallels her life with that of Woolf’s protagonist. While Laura spirals into suicidal despair, the surrealistic dream sequence reminiscent of Woolf’s 1941 drowning shocks her back to life and the birth of her daughter. The depiction of the creative process of Woolf’s novel is an affirmation of life, juxtaposed as it is with Virginia’s contemplation of death and the dead bird. Subsequent scenes have her plunging into the initial stages of writing the novel. The party that is central to each text is discussed Each text focuses on a party to be given by the Clarissa of Mrs Dalloway and The Hours. The preparation of the parties consumes the respective hostesses and both are aware of the superficiality of their endeavours. While she knows her husband Richard has important work in the government, Clarissa cannot differentiate between Armenians and Albanians and is aware of her inadequacy. She knows that both Peter and Richard ‘criticized her very unfairly, laughed at her very unjustly, for her parties.’ However, Clarissa’s success is the gift she offers others – bringing people together is an affirmation of life, a communion of lives. The word unlike signals the contrast between the two texts Unlike Clarissa Dalloway’s successful party, Clarissa Vaughan’s party – in honour of her former lover and AIDS sufferer Richard for his prestigious poetry award – becomes futile because of his suicide, and yet here too the composer offers an avowal of life. The dead poet’s mother, Laura, comes to the apartment and is treated sensitively by Clarissa’s daughter Julia, whose acceptance and non-judgemental attitude of the choices she made – abandoning her own family so that she might live – is an implicit affirmation. Julia’s dialogue earlier in the film with her own mother gives an affirmation of filial relationships. Like her namesake, Clarissa Vaughan, (Richard often refers to Clarissa as ‘Mrs Dalloway’ because she is self-effacing and distracts herself from her own life the way the Woolf character did 80 years earlier), creates meaning in her own life through the happiness she can give to others in her role as carer. Relationship between the two texts is further explored through the experience of the kiss The fluid nature of sexuality, unlived dreams, and repressed desires are explored through Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness style of writing. Clarissa’s sweetest kiss is the one she shares with the unconventional Sally Seton. This is reshaped and echoed in the film where each of the three central characters share a kiss, shown in a close-up shot, with another woman – Vanessa and Virginia, Kitty and Laura, then Clarissa and Sally, who are perhaps given the fulfilment their namesakes in the original text were denied because of the contextual restrictions of lateVictorian England, with its espousal of sexual restraint and strict social code of conduct. Sexual ambivalence and identity are significant and explicit concerns of the film. Each text seems to confirm that these repressed desires rob the protagonists of fulfilment and thus their lives are emotionally poorer. The discussion of another linking idea – suffering – in both texts is contextualised Both texts explore the idea of madness and both texts present this as an issue of great concern for their own particular context – the shellshocked World War I veteran, who, like his creator heard the birds speaking in Greek, and the AIDS sufferer whose final stages of the disease have brought him to madness. The representation of both characters is at once confronting and poignant, their ‘insanity’ shown as a heightened awareness of life, of being. Septimus Warren Smith’s interior monologues, his musings and scribblings, his anger towards his doctors and institutions offer insight through his wit: ‘The world has raised its whip; where will it descend?’ The madness caused by shellshock is dramatically and empathetically rendered in Woolf’s writing. The focus on AIDS is contextulaised Richard Brown’s emaciated physical appearance, demonstrating the horror of AIDS, an almost ubiquitous disease in the late 20th century, is exacerbated by the dim lighting effects in the shabby chic New York warehouse apartment. His poetry books lined up on Clarissa’s shelves likewise indicate a clever, sensitive and damaged man; we are aware at the conclusion of the film that Richard is the abandoned son of Laura. The final act of suicide links both characters – but the book and the film affirm the living. Clarissa Dalloway in her empathy and understanding of Septimus thinks she is very like him and interprets his death as an act of embracing life: ‘She felt glad he had done it; thrown it away.’ The representation of Clarissa Vaughan indicates that she too understands Richard’s decision. Conclusion links all the ideas Both texts conclude with an unambiguous affirmation. The novel ends with Peter Walsh’s excited, ‘It is Clarissa. For there she was’, the film with Laura’s, ‘It [her domestic life] was death. I chose life.’, then Virginia’s voiceover, ‘Always the years between us. Always the years. Always the love. Always the hours.’ These declarations demonstrate that in the midst of death, the importance of living and celebrating life with all its minutiae and ordinariness, its complications and sacrifices is an idea which connects both texts across the 80 years.

![Special Author: Woolf [DOCX 360.06KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006596973_1-e40a8ca5d1b3c6087fa6387124828409-300x300.png)