Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Paper

advertisement

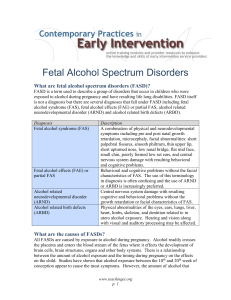

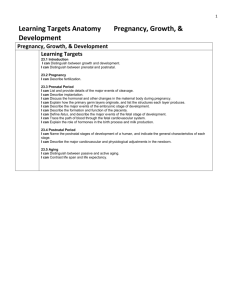

Running Head: ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 1 “Alcohol, Pregnancy and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)” Manuscript Submission by Gabriela Olivas RN, SNNP University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston School of Nursing GNRS 5633 Dr. Debra Armentrout, PhD, RN, MSN, NNP-BC and Dr. Leigh Ann Cates, PhD, APRN, NNPBC, RRT-NPS, CHSE November 20th, 2014 ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 2 Abstract The leading cause of intellectual disability is maternal alcohol abuse. The consumption of alcohol in any point in pregnancy may cause an array of disorders in the fetus known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. The various detrimental effects from the consumption of alcohol in the pregnant female can cause neurological, physical, social and emotional deficiencies in the fetus. The severity of birth defects resulting from exposure of the developing embryo or fetus to alcohol is determined by multiple factors, including genetic background, timing and level of alcohol exposure, and nutritional status. The identification of severity of the disorder is postnatal based on the clinical manifestations of the infant. Although no treatment is available, intervention is key to support and improve the quality of life of the affected individuals. Education is essential in preventing this disorder from occurring. The various economic, social, and emotional implications for the individual and their families can be detrimental. ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 3 Alcohol, Pregnancy and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Approximately 12% of women in the United States and over 20% worldwide drink alcohol during pregnancy.1 Most women stop drinking or at least decrease their alcohol consumption upon learning that they are pregnant.1 Still, roughly half of all pregnancies are unplanned, and many women are unaware they are pregnant until four to six weeks into pregnancy. As a result, they continue using alcohol at prepregnancy levels while preganant.1 Consequently, a significant proportion of women consume alcohol during the early stages of pregnancy before knowing they are pregnant. This exposes the fetus during the most critical time of development to the detrimental effects of alcohol. Indeed, studies show that alcohol exposure early in pregnancy may affect fetal development even if followed by later gestational abstinence.1 Alcohol consumption during any gestation of pregnancy causes fetal alcohol consumption. This can cause damaging physical and neurological defects, leading to any one of the array of disorders which are described as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders [FASD].2 FASD is an umbrella term used for a range of physical, mental, behavioral, and learning deficits that can occur in an individual whose mother drank alcohol during pregnancy.3 The most profound areas of prenatal alcohol exposure are on the fetus’s brain development, effecting both the cognitive and behavioral aspects of the infant.4 The incidence of FASD is believed to range from 0.2 to 2 per 1000 live births.5 Alcohol produces teratogenic effects in all gestations, with peculiar emphasis depending on the trimester of pregnancy in which the alcohol is consumed.6 As there is no exact dose-response relationship between the amount of alcohol ingested during the prenatal period, and given the gravity of damage caused by alcohol in the fetus, abstinence from alcohol at conception and during pregnancy is strongly recommended.6 ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 4 Pathophysiology When alcohol is consumed by a pregnant woman, it crosses the placenta and rapidly reaches the fetus.7 Infants who were exposed to alcohol in utero are at increased risk for a range of alcohol-related damage including any of the conditions in the FASD. Studies show equivalent fetal and maternal alcohol concentrations, suggesting an unrestrained bidirectional movement of alcohol between the diad.7 The fetus appears to depend on maternal hepatic detoxification because the activity of alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) in the fetal liver is less than 10% of that seen in the adult liver.7 In addition, the amniotic fluid acts as a reservoir for alcohol; thus, prolonging fetal exposure.7 The mechanism for the spectrum of adverse effects virtually all organ systems of the developing fetus is unknown.7 Ethanol, and its metabolite acetyldehydrate (the placenta deoxidizes ethanol to this substance), can alter fetal development by disrupting cellular differentiation and growth, disrupting DNA and protein synthesis and inhibiting cell migration. This is greatly due to the fact that the fetus experiences maternal alcohol levels at 50% of maternal levels.8 Ethanol and acetyldehydrate modify the intermediary metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.7 Both also interfere and decrease the transfer of amino acids, glucose, folic acid, zinc, and other nutrients across the placental barrier, indirectly disrupting fetal growth due to intrauterine nutrient deprivation.7 This process also interferes with the incorporation of amino acids into proteins. Acetyldehydrate affects cell membranes and cell migration altering embryonic tissue organization with dysmorphic changes.8 This may limit the number of fetal cells and lead to fetal growth restriction.8 Decreased placental transfer of linoleic and docosahexanoic acid may also alter fetal growth and development.8 ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 5 The detrimental effects may be due in part to variations in the metabolism of alcohol in the placenta by CYP2E1 and alcohol dehydrogenase.8 Elevated levels of erythropoietin in the cord blood of newborns exposed to alcohol are reported and suggest a state of chronic fetal hypoxia.7 Physiologic Impact The occasional social drinker to those that drink uncontrollably can have varying physiological effects on their fetus’s development depending on the gestational period and amount of consumption during pregnancy. First Trimester During the first trimester of human gestation, alcohol exposure can alter the normal development of the neural tube and crest, leading to microcephaly, hydrocephaly, ocular malformations and facial dysmorphology that characterize fetal alcohol syndrome [FAS].9 Alcohol fetal exposure induces a delay in the generation of cortical neurons, with a reduction in their number and their distribution.6 Because many women who drink alcohol are unaware of their pregnancy, there is a link between cardiac defects and alcohol consumption within the first trimester.6 It may be embryologically too late, if a woman stops drinking after learning that she is pregnant since the fetus’ heart might not have correctly formed.10 Second Trimester During the second trimester, alcohol exposure reduces intrauterine and postnatal growth. It also affects the proliferation of glial and neuronal precursors, with a strong modification in the migration of cortical neurons.6 These abnormalities are likely the cause of the agenesis, or malformation of the corpus callosum, or ventriculomegaly, and of a small cerebellum.6 These findings have been noted in autopsies of newborns exposed to alcohol in the second trimester.6 ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 6 Third Trimester During the third trimester, the brain goes through a period of quick growth often called “brain growth spurt.” The neurons are more prone to the apoptotic effects of alcohol.9 Through this mechanism, damage is caused to the neuronal plasticity, which is the ability of the brain to be changed in relationship to previous experiences.6 During development, neuronal plasticity plays a key role in the processes of learning and memory.9 The proposed oxidative stress alcohol induces explains the mechanism through which alcohol can exert harmful teratogenic effects on the brain during the third trimester.11 Clinical Manifestations The leading cause of intellectual disability is maternal alcohol abuse.10 FASD is related to an extensive range of neurobehavioral deficits, including, poorer verbal learning and memory, lower IQ, poorer attention and executive function and slower cognitive processing speed.12 These key characteristics develop in individuals with FASD. The clinical manifestations post birth and within the first 36 hours after birth seen in these infants are discussed below. At birth, FASD can cause a distinct set of facial anomalies that alert the health care provider that the patient was affected by alcohol consumption in utero. FAS, the most severe form of FASD, is characterized by a distinctive set of facial anomalies. The manifestations of these facies include short palpebral fissures, flat midface, thin upper lip (vermilion border), flat or smooth philtrum, microcephaly and pre- or postnatal growth retardation.13 Infants with FASD also develop associated features such as epicanthal folds, low nasal bridge, short nose, and micrognathia.14 The infant may also have decreased muscle tone, poor coordination and heart defects such as ventricular septal defects (VSD) or atrial septal defects (ASD).7 ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 7 Central nervous symptoms can appear within 24 hours after delivery and includes tremors, irritability, twitching, decreased tolerance to noise, or hyperacusis, hyperventilation, hypertonicity, opisthotonos, and seizures.13 These symptoms may be severe, but they are usually of short duration. There is an increased risk of both intracranial hemorrhage and white matter CNS damage in premature infants of women who were heavy alcohol users (more than 7 drinks per week).13 Diagnostic Approach FASD diagnosis is difficult because prenatal exposure information is often lacking, and large proportion of affected children do not exhibit the distinctive facial anomalies, and no distinctive behavioral phenotype has been identified.12 There are three major factors that must be addressed in the individual when a FASD diagnosis is considered: (1) physical growth, development, and structural defects (i.e., dysmorphology); (2) cognitive and neurobehavioral function; and (3) maternal exposure and risk.2 In 1996, the Institute of Medicine published specific diagnostic criteria for FAS with confirmed maternal alcohol exposure, FAS without confirmed maternal alcohol exposure, partial FAS with confirmed alcohol exposure, alcohol related birth defects (ARBD), and alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders [ARND].5 Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS): FAS occurs at the most critical end of the FASD spectrum. The diagnosis is defined by the following strict criteria: Three specific facial abnormalities which are a smooth philtrum, thin vermillion border, and small palpebral fissures;15 Growth deficits (e.g. lower‐than‐average height, weight, or both); and15 Central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities (structural, neurological, functional or a combination).15 ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 8 Partial FAS: When a person does not meet the full FAS diagnostic criteria but has a history of prenatal alcohol exposure, some of the facial abnormalities as well as a growth problem or CNS abnormalities may still reveal FAS.15 Alcohol‐Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder (ARND): People with ARND might have intellectual disabilities and problems with behavior and learning.15 Alcohol‐Related Birth Defects (ARBD): People with ARBD might have problems with the heart, kidneys, and/or bones, as well as with hearing and/or vision.15 A new test capable of detecting fetal fatty acid ethyl esters in the meconium of newborns of heavy alcohol users may be useful to identify infants in need of early health, developmental and psychosocial intervention and may enhance clinical research involving prenatal drug and alcohol exposure.3 Therapeutic Options Prevention The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends alcohol abstinence preconceptionally, during pregnancy, screening of all pregnant women for alcohol use, and referral of pregnant alcohol abusers for assessment and treatment.3 The Department of Health and Human Services and the Office of the Surgeon General, released an updated Advisory on Drinking and Pregnancy in 2005 advising women who are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or at risk of becoming pregnant to abstain from alcohol use. Moreover, research has shown that earlier intervention, results in more successful the individuals are with these developmental disabilities. Guidelines for screening and management of FASD include universal screening of pregnant women for alcohol use, so that appropriate management can be provided.3 A brief ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 9 questionnaire such as the TWEAK (Tolerance of number of drinks needed to feel high; Worry or concerns by family or friends about drinking behavior; Eye opener in the morning; blackouts or Amnesia while drinking; self-perception of the need to [K] cut-down on alcohol use) is helpful to nearly all obstetric settings for the identification of pregnant women at risk. TWEAK allows referrals to be made for further drug or alcohol abuse and psychosocial assessment and treatment.3 Another key element to consider is whether a woman has an alcohol dependence prior to conception. If so, contraception consultation and services should be offered. It is recommended that pregnancy be delayed until it can be an alcohol-free pregnancy.16 Due to the devastating effects of alcohol on the fetus, prenatal education is fundamental to preventing FASD. Intervention It is imperative to identify the possible diagnosis of FASD as soon as possible to ensure better outcomes.17 Once an FASD is identified in a specific patient, prompt referrals and enrollment in indicated services are required to achieve the best outcomes.17 The key to early diagnosis is to keep the diagnostic possibility in the broad differential diagnoses of growth and developmental disorders.17 No two people with an FASD are exactly the same. Early diagnosis is important, so that the affected individuals can receive the needed support in a protective setting. FASDs can include physical or intellectual disabilities, as well as problems with behavior and learning. These symptoms can range from mild to severe.15 Treatment services for people with FASDs differ for each person depending on their symptoms.15 There is no cure for FASDs, but early intervention may improve primary effects (i.e., language, emotion dysregulation) and prevent secondary effects (i.e., academic, legal, psychiatric problems) related to FASDs.15 Patients benefit from early diagnosis and aggressive intervention with physical, ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 10 occupational, speech and language, and educational therapies.15 The interventions must be individualized, multimodal, and precise to the individual and their family and continue across the individual’s lifespan. Economic, Emotional and Social Implications People with FASD often experience a wide range of health problems such as birth defects, growth problems, cognitive delay, and speech and language difficulties. Infants affected by FASD are also more susceptible to cardiac anomalies, urogenital defects, skeletal abnormalities, and visual and hearing problems.18 The economic, emotional and social implications related to FASD are daunting, but preventable. Economic Implications Given the wide array of disabilities, individuals who are affected with FASD may have special needs that require lifelong help.18 Without the crucial support, people with FASD are at a high risk of developing secondary disabilities such as: mental health problems, trouble with the law, dropping out of school, becoming unemployed, homeless or developing alcohol and drug problems.18 This leads to elevated costs throughout a lifetime. FASD costs $6 billion annually in the United States.19 It costs $1.4 million to treat one person with FAS over their lifetime.19 The total lifetime cost per individual include estimates of medical treatment, home and residential care, special educational services and productivity losses with patients with FASD of all ages.19 Emotional/Social Implications Children diagnosed with FAS or those affected by FASD often come from unstable families and may be at greater risk for physical abuse, sexual abuse and neglect.19 As many as 85% of children with FASD are being raised by grandparents, other relatives, foster parents, or ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 11 adoptive parents.19 It is paramount to counsel the childcare provider and their families on the importance of caregiver attachment.19 Between a child’s birth and their third birthday, it is particularly important for developing a stable and nurturing environment for the infant. Children who may have FAS and are in the foster care system are at an increased risk for negative attachment and reactive attachment disorder [RAD].19 Understanding a diagnosis can help families set realistic expectations and facilitate appropriate treatment, intervention, and planning.19 Because the life skills affected by prenatal alcohol exposure vary greatly, the correct intervention is unique for each individual with FAS and their family.19 The CDC has identified age-specific services that are helpful to individuals with FAS.19 The most effective interventions are those that are geared towards an individual’s developmental level. Conclusion The worldwide rate of FAS has been estimated to be 1.9 per 1,000 live births.1 Recent studies show an elevated FAS rate of 2 to 7 per 1,000 in the US, and FASD incidence is estimated to be 2%-5% among elementary school children in the US.1 Alcohol now is recognized as the leading preventable cause of birth defects and developmental disorders in the United States.14 The severity of birth defects resulting from exposure of the developing embryo or fetus to alcohol is determined by multiple factors, including genetic background, timing and level of alcohol exposure, and nutritional status.14 Infants diagnosed with FASD have serious, lifelong consequences related to alcohol exposure in utero. Early diagnosis is important so that the affected children can receive the support they need in a protective environment. The National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (n.d.) best sums up the relationship of alcohol ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD and pregnancy by stating, “Alcohol and Pregnancy. No safe amount. No safe time. No safe alcohol. Period 1.” 12 ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 13 References 1. Balachova, T., Bonner, B. L., Chaffin, M., et al. Brief FASD prevention intervention: physicians’ skills demonstrated in a clinical trial in Russia. Addict Sci Clin Prac. 2013; 8(1), 1-10. 2. May, P. A., & Gossage, J. P. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Not as simple as it might seem. Alcohol Res Health, 2011; 34(1), 15. 3. Martin, R. J., Fanaroff, A. A., & Walsh, M. C. (2011). Pharmacology. In: Fanaroff and Martin's neonatal-perinatal medicine: diseases of the fetus and infant. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011: 708-757. 4. Riley, E. P., Infante, M. A., & Warren, K. R. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: an overview. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011; 21(2), 73-80. 5. Douzgou, S., Breen, C., Crow, Y., et al. Diagnosing fetal alcohol syndrome: new insights from newer genetic technologies. Arch Dis Child. 2012; 97(9), 812-817. 6. Paoletti, A. M., Atzeni, I., Orrù, M., et al. Alcohol and pregnancy. Journal of Pediatric and Neonatal Individualized Medicine (JPNIM). 2013; 2(2), e020215. 7. Vaux, K. K. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Medscape. 2012; Retrieved from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/974016-overview 8. Blackburn, S. T. Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics during the perinatal period. In: Maternal, fetal, & neonatal physiology: a clinical perspective.4th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2013: 183-213. 9. Medina, A. E. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and abnormal neuronal plasticity. The Neuroscientist. 2011: 17(3), 274-287. 10. Sadler, T. W., & Langman, J. Langman's Medical Embryology. 12th ed. ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 14 Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. 11. Brocardo, P. S., Gil-Mohapel, J., & Christie, B. R. (2011). The role of oxidative stress in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Brain research reviews, 67(1), 209-225. 12. Jacobson, S. W., Jacobson, J. L., Stanton, M. E., Meintjes, E. M., & Molteno, C. D. Biobehavioral markers of adverse effect in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011; 21(2), 148-166. 13. Gomella, T. L, Cunningham, M. D. & Eyal, F. G. Infant of a substance-abusing mother. In: Neonatology: Management,Procedures, On-call Problems, Diseases and Drugs.7th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Education; 2013: 715-724. 14. Warren, K. R., Hewitt, B. G., & Thomas, J. D. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: research challenges and opportunities. Alcohol Res Health. 2011; 34(1), 4. 15. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. 2011. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/treatments.html 16. Floyd, R. L., Jack, B. W., Cefalo, R., et al. The clinical content of preconception care: alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug exposures. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 199(6), S333-S339. 17. Schaefer, G. B., & Deere, D. Recognition, diagnosis and treatment of fetal alcohol syndrome. J Ark Med Soc. 2011; 108(2), 38-40. 18. Popova, S., Stade, B., Bekmuradov, D., Lange, S., & Rehm, J. What do we know about the economic impact of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder? A systematic literature review. Alcohol and Alcohol. 2011; 46(4), 490-497. 19. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (NOFAS) Website. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.nofas.org ALCOHOL, PREGNANCY, AND FASD 15