EFFICACY OF WOUND INFILTRATION USING

advertisement

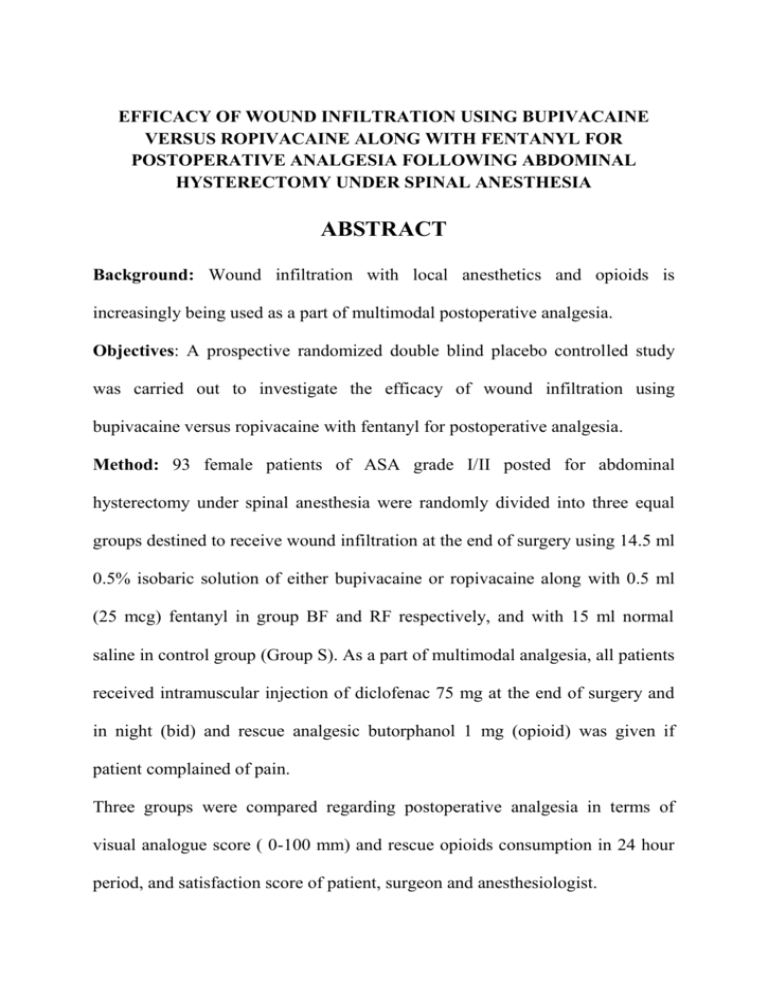

EFFICACY OF WOUND INFILTRATION USING BUPIVACAINE VERSUS ROPIVACAINE ALONG WITH FENTANYL FOR POSTOPERATIVE ANALGESIA FOLLOWING ABDOMINAL HYSTERECTOMY UNDER SPINAL ANESTHESIA ABSTRACT Background: Wound infiltration with local anesthetics and opioids is increasingly being used as a part of multimodal postoperative analgesia. Objectives: A prospective randomized double blind placebo controlled study was carried out to investigate the efficacy of wound infiltration using bupivacaine versus ropivacaine with fentanyl for postoperative analgesia. Method: 93 female patients of ASA grade I/II posted for abdominal hysterectomy under spinal anesthesia were randomly divided into three equal groups destined to receive wound infiltration at the end of surgery using 14.5 ml 0.5% isobaric solution of either bupivacaine or ropivacaine along with 0.5 ml (25 mcg) fentanyl in group BF and RF respectively, and with 15 ml normal saline in control group (Group S). As a part of multimodal analgesia, all patients received intramuscular injection of diclofenac 75 mg at the end of surgery and in night (bid) and rescue analgesic butorphanol 1 mg (opioid) was given if patient complained of pain. Three groups were compared regarding postoperative analgesia in terms of visual analogue score ( 0-100 mm) and rescue opioids consumption in 24 hour period, and satisfaction score of patient, surgeon and anesthesiologist. Results: All 31 (100%) patients of group S received rescue opioids [ 1 dose= 3 (9.67%), 2 doses = 26(83.8%), 3 doses = 2(6.45%) patients]; whereas rescue opioid was required in 21(67.7%) patients of group BF and 26 ( 83.8%) patients of group RF, and all of them received single dose. Thus total rescue opioid (butorphanol) consumption was significantly higher in group S (61 mg), as compared to group BF (21 mg) and group RF (26 mg), p= 0.000. However group BF and group RF were comparable p=0.473. (Group S > group RF~ Group BF). Mean VAS score at rest, cough and movement was significantly less and satisfaction of patient, surgeon and anesthesiologist was significantly higher in group BF than in group RF than in group S, p<0.05. No adverse effects related to wound infiltration were observed. Conclusion: We conclude that wound infiltration using bupivacaine or ropivacaine with fentanyl is an easy, safe and effective technique for providing postoperative analgesia. Among two local anesthetics bupivacaine seems to be superior to ropivacaine in wound infiltration in terms of significantly less pain score and better satisfaction score, however rescue analgesic consumption was comparable. KEY WORDS: wound infiltration, bupivacaine, ropivacaine, fentanyl, postoperative analgesia, multimodal analgesia. INTRODUCTION Total abdominal hysterectomy is commonly performed via a pfannenstial incision and causes moderate to severe pain, which is often multifactorial and can be attributed to combination of incision pain, pain from deeper visceral structures, and dynamic pain on movement, such as during straining, coughing or mobilizing that may be severe1. Injured nerve fibers innervating the site of incision/ retraction and sutures generate pain impulses. Increased inflammatory mediators at the surgical site also sensitize uninjured and injured nerve fibres. Transmission of pain from the wound is reduced by local anesthetic application, and the local inflammatory response to the injury is also suppressed. Consequently hyperalgesia due to sensitization of nociceptors may be prevented2. A traditional approach for post-operative pain control includes inhibition of peripheral nerves innervating the surgical site by local wound infiltration3. It is a method of post operative analgesia commonly used alone or alongwith other analgesic regimens. It also reduces opioids consumption, minimizes opioid adverse reactions, reduces nursing work, decreases resting pain, pain on motion, and thus allows better patient mobility4. Various clinical studies had been published which support the analgesic properties of peripheral use of opioids and numerous mechanism have been stated for this action through peripheral opioid receptors3,5,6. Bupivacaine has been the long-acting local anaesthetic agent of choice since a long time7. Ropivacaine has been introduced as a long-acting local anesthetic agent with potential advantages over bupivacaine, particularly with respect to reduced cardiac toxicity8. Efficacy of both bupivacaine9,10 and ropivacaine11,12 for wound infiltration as a component of multimodal post operative analgesia had been studied with varying results. But the comparison of analgesic effect of these two agents in wound infiltration has not been much investigated13. Hence the present study was undertaken to test the hypothesis whether wound infiltration using bupivacaine or ropivacaine along with fentanyl as a part of multimodal analgesia could reduce the opioids consumption in first 24 hours in post operative period. The analgesic profile of two local anesthetics was also compared. MATERIALS AND METHODS After institutional ethical committee clearance, this prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind study was carried out at Department of Anesthesia in RNT medical college attached to MB Hospital in Udaipur (Rajasthan). Basis of sample size: The number of patients required for the study was calculated on the basis of total opioid consumption during 24 hrs. We expected a reduction in opioid consumption by 25% in the group given local anesthetic infiltration. Assuming = 0.05, we calculated that we would need 93 patients (31 in each group) to achieve, a power of 90% ( = 0.9). Patient selection: 93 female patients of age group 20-65 years, ASA physical status I and II, undergoing elective total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) using pfannestial incision were enrolled in the study. After explaining the study procedure, written informed consent regarding participation in the study was taken from all of the patients. Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if TAH was scheduled for malignancy or if there was a history of chronic pain, continuous use of analgesic drugs, patients with a history of clinically significant cardiovascular, pulmonary, hepatic, renal, neurologic, psychiatric, or metabolic disease. Patients having severe obesity (BMI > 35 kg/m2), coagulation disorder, on anticoagulants, severe spinal deformity, allergy to local anesthetic, or any contraindication to spinal anesthesia were excluded from the study. Randomization, group allocation and blindness to the study: 93 selected patients were randomly assigned to 3 equal groups using sequentially numbered, opaque sealed envelopes depending upon the drugs used for wound infiltration (15ml) at the end of surgery. Group S (Control group): received wound infiltration using normal saline(15 ml) Group BF (Bupivacaine group): received wound infiltration using 14.5 ml (72.5 mg) of isobaric bupivacaine (0.5%) with 0.5 ml (25mcg) fentanyl. Group RF (Ropivacaine group): received wound infiltration with 14.5 ml (72.5 mg) of isobaric ropivacaine (0.5%) with 0.5ml (25mcg) fentanyl. To provide double blindness to the study, drugs for wound infiltration were prepared by a separate anesthesiologist who was not involved further in the study .Wound infiltration was done by surgeon who was not aware of group allocation, and not involved in data recording. Data were recorded by an independent anesthesiologist who was not aware of group allocation. Patients had given consent for participation in the study but not aware of group allocation. Anesthesia technique:- After thorough pre-anesthetic evaluation patients were taken in elective operation theatres after 8 hours fasting. Standard monitoring of heart rate (HR), non invasive blood pressure (N.I.B.P.), electrocardiography (E.C.G.) and pulse oximetry (SpO2 ) was done with a multipara monitor. After taking an intravenous access with 18 G cannula, infusion of 500ml Ringer lactate was given, all patients were premedicated with 1mg midazolam intravenously. Base line heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure was measured before spinal anesthesia. Under full aseptic precautions in all patients lumbar puncture was performed at L3-L4 intervertebral space in lateral decubitus position through a midline approach using 25 G quincke spinal needle. Correct needle placement was identified by free flow of cerebrospinal fluid and 3ml (15mg) of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine was given for subarachnoid block. Standard monitoring was done throughout the operation. E.C.G. and pulse-oximetry was monitored continuously while N.I.B.P. was monitored every 3 min for first 15 min, thereafter every 5 min till completion of surgery. Hypotension (decrease in systolic B.P. of 20% of baseline or less than 100 mm of Hg) was treated with i.v. bolus of 6mg ephedrine hydrochloride. Bradycardia (<60 beat/min) was treated with i.v. bolus of 0.3 – 0.5 mg of atropine sulphate. Surgical technique: The total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo– oophorectomy was performed in all the patients following standard steps: abdomen was opened in layers via pfannenstial incision, and then infundibulopelvic ligament was clamped followed by clamping of uterine artery and Mackenrodts ligament. Then uterus along with bilateral ovaries and cervix was removed (TAH with BSO) vault was closed, hemostasis achieved and abdomen closed in layers. Wound infiltration technique: The surgeon who was blinded to the treatment groups was asked to infiltrate all layers of the abdominal wall during closure, including muscle and cutaneous layers, using drugs as per group allocation. For postoperative analgesia: Multimodal analgesic regime was followed in which patients received intramuscular injection of diclofenac 75 mg [ nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)] immediately after wound infiltration and subsequently after 12hr.Thus each patient received two doses of diclofenac during the study period of 24 hours. Rescue analgesic in form of butorphanol 1mg (opioid) was given as slow iv injection whenever patient complained of pain in the postoperative periods, or VAS was > 40 mm at rest. Data recording: In the postoperative period, assessments were made at shifting of the patient in ward (0hr) as baseline then at 1hr, 2hr, 6hr, 12hr and 24 hr, by anesthesiologist blinded to the treatment groups. Pain at rest, cough and on movement (induced by leg raising as bending of the knees) was assessed on Visual Analog Scale (0-100 mm) as 0- no pain, 100- worst imaginable pain at above time intervals. In addition, total rescue analgesic (opioid) requirement in terms of number of doses and total dose in mg in 24 hrs was recorded. Heart rate (HR), Systolic blood pressure (SBP), Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was also recorded at above time intervals. Sedation was assessed at same time intervals as VAS using a categorical scale (1: awake and alert, 2: awake but drowsy responding to verbal stimulus, 3: drowsy but rousable responding to physical stimulus, 4: unrousable not responding to physical stimulus. In addition, any episode of nausea and vomiting were recorded during the 24 hr postoperative period and rescue antiemetic ondansetron 4mg i.v. was given for nausea, vomiting and repeated if necessary. Any other side effect if occurred was noted. Satisfaction score of patients, surgeon and anesthesiologist regarding post operative analgesia was assessed at 24 hours postoperatively and graded as: 0-poor, 1-satisfactory, 2-good, 3-excellent, and the study was declared as complete. Statistical analysis: Data were entered and analyzed with the help of MS Excel EPI info 6 and SPSS. Qualitative or categorical data were presented as number (proportion) and compared with Chi-square test. Quantitative or continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD and compared using student‘t’ test. ANOVA was applied as per need as test of significance. A post hoc test was used to assess intergroup differences. p< 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Results All the three groups were comparable regarding mean age (p=0.367), mean weight (p=0.384), residence (p=0.565) and education status (p=0.840).(Table 1) The base line vital parameters (HR, SBP, DBP) were statistically comparable in all the three groups (p>0.05). There was no significant difference in HR, SBP and DBP at various time intervals during postoperative period (0-24hr) in three groups, as compared to baseline (p>0.05)and no significant intergroup variations were observed ,( p > 0.05). Post-operative analgesia: VAS score : In all the three groups, 0, 1, and 2 hours postoperatively mean VAS was found 0 at rest, cough, and movement due to persistence effect of spinal anesthesia .Mean VAS at rest, cough and movement at 6, 12 and 24 hours was significantly less in group BF and group RF as compared to group S, p<0.05. Mean VAS was also significantly less in group BF than in group RF, p<0.05. Thus mean VAS was in order of group BF< group RF< group S. (Table 2) Rescue analgesic consumption During 24 hours postoperatively, rescue analgesic was required by all 31 patients (100%) in Group S. Out of these 3(9.67%) patients received a single dose, 26(83.8%) received 2 doses and 2(6.45%) required 3 doses. Whereas opioids were required in 21 (67.7%) patients in Group BF and 26 (83.8%) patients in Group RF and all received the single dose. It was noteworthy that 10(32.2%) patients in group BF and 5 (16.1%) patients in group RF did not require any rescue opioids in 24 hours post operative period. Requirement of rescue analgesic in postoperative period (24hr) in terms of total number of doses and total dose in mg was significantly more in group Group S(61mg) as compared to Group BF (21mg) and Group RF (26mg), p= 0.000; however, group BF and group RF were comparable, p=0.473. Thus rescue analgesic requirement was GroupS > GroupRF ≈GroupBF. Requirement of rescue analgesic(butorphanol) in terms of mean dose in mg for each patient was significantly more in GroupS(1.96±0.40mg), as compared to GroupBF (0.667±0.47mg), p=0.035 and GroupRF (0.83±0.37 mg), p=0.028; nevertheless, GroupRF and GroupBF were comparable P=0.086 . Wound infiltration with ropivacaine and bupivacaine along with fentanyl was found to reduce rescue analgesic consumption by 57.3% (group RF) and 65.5% (group BF) respectively as compared to control group (group S), which was statistically significant, p=0.000(Table 3). Satisfaction score Mean satisfaction score of patient, surgeons and anesthesiologist were significantly higher in the GroupBF (1.35±0.48, 1.71±0.46, 1.73±0.45 respectively) and GroupRF (0.94±0.30, 1.51±0.25, 1.51±0.25 respectively), p=0.000; as compared to group S (0.42±0.50, 0.97±0.48, 0.97±0.49 respectively), p=0.000. Mean Satisfaction score of patients, surgeon and anesthesiologist in GroupBF was also significantly higher than in GroupRF, p= 0.000. Thus satisfaction score was GroupBF > GroupRF > GroupS. Sedation score Mean sedation score was significantly more in group S(1.06±024) as compared to group BF(1) and group RF(1) in which all patients remained alert at all time intervals , p=0.000. Postoperative adverse effects: Emetic episode were minimal in present study. Only 1 (3.2%) patient each in group S and group BF had vomiting and received ondansetron 4 mg. None of the patient in the study had other side effects such as pruritis, wound infection, wound rupture, wound hematoma, delayed wound healing etc. Table 1: Demographic characteristics Group S Group BF Group RF (n=31) (n=31) (n=31) 20-40 19 (33.3%) 21 (36.8%) 17 (29.8%) Age >40-60 12 (35.2%) 8 (23.5%) 14 (41.1%) (years) >60 0 (0%) 2(6.45%) 0 (0%) Mean ±SD 40.5±6.52 39.8±6.65 39.9±7.31 40-60 30 (35.2%) 28 (32.9%) 27(31.7%) 1(12.5%) 3(37.5%) Mean ±SD 53.2±5.33 53.7±6.43 52.8±6.15 Rural 20 (39.2%) 16 (31.3%) 17 (33.3%) Urban 11 (27.5%) 15 (37.5%) 14(35.0%) Literate 18(34.61%) 18(34.61%) 16 (30.7%) Illiterate 13 (30.9%) 13 (30.9%) 17(54.8%) Variable 0.367 Weight(kg) >60-80 Residence Education P Value 4(50.0%) 0.384 0.565 Data are expressed as mean ±SD or n (%) as appropriate 0.840 TABLE 2 Postoperative analgesia in terms of VAS score (0-100 mm) at various time intervals in three groups Time VAS score P value GrS vs GrBF GrS vs GrRF GrBF vs GrRF 24.8±2.56 0.043 0.035 0.025 24.7±3.86 32.8±4.28 0.034 0.024 0.023 51.0±8.51 27.7±4.05 37.8±5.85 0.046 0.026 0.025 R 36.8±7.02 12.3±3.61 22.6±2.21 0.030 0.023 0.028 C 45.5±6.63 21.0±3.96 30.8±3.85 0.043 0.040 0.025 M 49.2±7.76 23.9±5.58 34.5±4.43 0.046 0.032 0.022 R 35.6±6.25 11.3±5.09 21.2±2.85 0.039 0.026 0.022 C 43.9±6.29 16.8±5.09 28.0±4.15 0.034 0.043 0.035 L 46.8±7.8 20.3±6.94 31.5±3.08 0.042 0.022 0.037 Overall R 36.8±1.30 13.4±2.92 22.8±1.81 0.030 VAS (6C 43.5±1.31 20.8±3.95 30.5±2.41 0.032 24 hours) M 49.0±2.10 23.9±3.70 34.6±3.51 0.036 R-Rest, C-cough, M-Movement (on leg raising). Data are expressed as mean ± SD and post-hoc test (ANOVA) used. 0.043 0.046 0.045 0.048 0.046 0.049 0 hr 1 hr 2 hr 6 hr 12 hr 24 hr Gr (S) Gr (BF) Gr (RF) R 0 0 0 C 0 0 0 L 0 0 0 R 0 0 0 C 0 0 0 M 0 0 0 R 0 0 0 C 0 0 0 M 0 0 0 R 38.2±8.02 16.8±5.09 C 46.5±8.68 M Table 3: Comparison of rescue analgesic requirement in three groups in first 24 hours postoperatively Rescue analgesia P value Group n=31 No. of requiring analgesic Patient distribution according to no. of doses patient rescue 31(100%) S Group BF n= 31 Group n=31 21(67.7%) 26(83.8%) RF No dose 0 10(32.3%) 5(16.2%) Single dose 3(9.67%) 21(67.7%) 26(83.8%) Two doses 26(83.8%) 0 0 Three doses 2(6.45%) 0 0 61 21 26 Total no of doses of rescue analgesic Total no. dose in mg of rescue analgesic (butorphanol) (mg) 61 21 26 Mean dose in mg for each patient 1.96±0.40 0.677±0.47 0.83±0.37 GrS/ GrBF GrS/ GrpRF GrpBF/ GrpRF 0.162 0.515 0.473 0.000 0.000 0.473 0.000 0.000 0.473 0.035 0.028 0.086 Data are expressed as mean ±SD or n(%) as appropriate DISCUSSION Opioids remain the primary analgesic agent for management of acute postoperative pain after major surgery; opioid related adverse effects inhibit rapid recovery and rehabilitation14. Currently, the American society of Anesthesiologists task force on acute pain management advocates the use of multimodal analgesia15. The combination of different analgesic agents in multimodal analgesia act by different mechanisms and at different sites in the nervous system. This provides additive or synergistic analgesia with lowered adverse effects of sole administration of individual analgesic14. As such, one approach for multimodal analgesia is the use of regional anesthesia and analgesia to inhibit the neural conduction from the surgical site to the spinal cord which decreases spinal cord sensitization14. This was also followed in present study where all hysterectomies were conducted under spinal anesthesia using 15 mg of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine. Guidelines for postoperative acute pain management specifies that “unless contraindicated all patients should receive round the clock regimen of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs or cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors (COX2) or acetaminophen”15. Mechanism of action of NSAIDs includes inhibition of the synthesis of prostaglandins both in the spinal cord and at the periphery. Thus it decreases the hyperalgesic state after surgical trauma and decreases postoperative opioid requirement14. All patients received intramuscular injection of diclofenac 75 mg on conclusion of the surgical procedure and at 12 hr interval thereafter as a part of multimodal post-operative analgesia regimen in the present study. Wound infiltration at the time of closure had been described as a part of multimodal analgesia and demonstrated to have an analgesic sparing effect and has the major influence on the patients’ ability to resume their normal activities of daily living10. Due to the local application, transmission of pain from the wound is reduced, and the local inflammatory response to the injury is suppressed. Consequently sensitization of nociceptors, and the ensuing hyperalgesia may be prevented2. Various agents like local anesthetics, opioids, NSAIDs have been used for wound infiltration, but with varying results3.16.17 Opioid receptors have been demonstrated in the peripheral nerve ending of afferent neurons. Blockade of these receptors with peripherally administered opioids is believed to result in analgesia3. Fentanyl5, morphine18, bupernorphine3, tramadol6 have been used for wound infiltration and were found to improve postoperative analgesia. Tverskoy et al5 reported that spontaneous and movement associated pain measured 24 hr postoperatively was decreased with the addition of fentanyl for wound infiltration (compared with the control) by approximately half ,and prolonged the duration of anesthesia by approximately 50%.Therefore in present study 25mcg fentanyl was used as an adjuvant along with local anesthetic for wound infiltration. When wound infiltration with bupivacaine or ropivacaine alongwith fentanyl was done as a part of multimodal analgesia in our study it resulted in significant improvement in postoperative analgesia. It allowed a significant reduction in pain scores and opioid consumption in first 24 hours postoperatively and this led to a significantly better satisfaction of patient, surgeon and anesthesiologist regarding postoperative pain. Wound infiltration by local anesthetics had been found effective in providing post operative analgesia in previous studies11,16,18,19. Local anesthetic application to wound can provide analgesia through various mechanisms. Firstly, they inhibit the transmission of pain from nociceptive afferents from the wound surface. Secondly, local inflammatory response to injury that sensitizes nociceptive receptors and contributes to pain and hyperalgesia, is also prevented by local anaesthetics. In addition they decrease the release of inflammatory mediators from neutrophils and neutrophil adhesion to the endothelium. They also decrease the formation of free radicals and edema20. Local anesthetic infiltration could alter the perception of deeper visceral pain by blocking the superficial component of pain16,21. The analgesic action of local anesthetics can be enhanced by infiltration of opioids in addition to local anesthetics3,5,18 .Opioids inhibit the neuronal firing by increasing the potassium current and decreasing calcium current in sensory neurons. They also block the transmitter release and calcium dependent release of excitatory pro-inflammatory compounds e.g. substance P contributing to their analgesic and anti –inflammatory actions. The anti-nociceptive effect of opioids is increased by inflammation in various ways. The perineurium (normally an impermeable membrane) is disrupted by presence of inflammation and it enhances the entry of various mediators like corticotrophin releasing hormones, interleukin 1B and other related cytokines. Inflammation increases the release of peptides from immune cells leading to activation of opioid receptors 3. Inflammation activates the previously inactive opioid receptors. In addition it also increases the receptor up- regulation (increase in their number in peripheral nerve terminals) thus potentiates the analgesic properties of opioids22. Fentanyl’s pharmacokinetic variables also allows it to stay in the muscle and fat compartments for many hours, the mean transit time for fat tissue being 1418 min23,24.After a bolus dose administration of fentanyl its action on opioid receptors in the wound area continue beyond 24 hrs and thus reduces the wound hyperalgesia5. In contrast some authors found that there was no significant difference in pain scores or rescue analgesic consumption in postoperative period in wound infiltration groups10,25. This ineffectivity of wound infiltration was attributed to various possibilities like inadequate dose or concentration of local anesthetic, inter-individual differences in patients perception of pain, difference in opioid effect or difference in pharmacokinetics. Some gave explanation that pain arising from viscera and deeper peritoneal layers is of greater significance than that from cutaneous, subcutaneous and muscular layer of a wound incision, afferent from deeper structure would be unaffected by wound infiltration10,25. The relative contribution of somatic and visceral pain after abdominal surgery is unknown and difficult to eluciadate26. Pfannenstial incision is used to perform total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. It is associated with extensive dissection and tissue damage during surgery. Thus it contributes to both somatic and visceral pain27. Local anesthetic infiltration near surgical wound decreases the somatic pain by altering peripheral pain transduction by inhibiting the transmission of noxious impulses from the site of injury28. According to some neural pain pathway theories, sensitization of nervous system to painful sensation occurs by stimulation of superficial pain receptors29. Alteration of perception of deeper visceral pain can be done by elimination of some of the superficial component of pain 30.The wound infiltration of local anesthetics is also effective in reducing postoperative narcotic requirements which has been observed in various studies 18,27 including ours. But the explanation regarding the mechanism of local anesthetics in decreasing the noxious impulses generated by visceral tissues distant to the site of drug infiltration is difficult27. Systemic analgesic effect may also occur due to systemic absorption of local anesthetic drugs31. This is supported by the observation that local anesthetics decrease dorsal horn neuronal excitability when administered systemically to decerebrated animals 32 . Certainly wound infiltration technique involves large volumes leading to significant systemic levels of local anesthetic or opioids. In present study 14.5 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine or ropivacaine (72.5mg) and 25mcg of fentanyl were infiltrated in the wound. In view of the large volumes and milligram doses of local anesthetics it would seem sensible to use a drug with a lower toxicity. Serious and sometime lethal cardiac toxicity has been described with bupivacaine, particularly when large doses are used. The cardiotoxicity of ropivacaine has been well shown to be significantly less than that of bupivacaine. In addition the cardiotoxic manifestations are easier to manage7. When wound infiltration with bupivacaine and ropivacaine was compared in the present study, efficacy of postoperative analgesia in terms of pain score (VAS score) was significantly superior in bupivacaine group as compared to ropivacaine group however there was no significant difference in opioid consumption in both the groups. Ropivacaine has a clinical profile similar to that of bupivacaine, and minimal difference reported between the two anesthetics are mainly related to the slightly different anesthetic potency, with racemic bupivacaine > ropivacaine33. It has been reported that relative analgesic potencies of ropivacaine: bupivacaine were 0.6 (for epidural minimum local analgesic concentration) and 0.65 (for intrathecal minimum local analgesic dose) and relative motor block potency of ropivacaine : bupivacaine was 0.66 after epidural administration. Ropivacaine is a levoisomer of bupivacaine and has propyl group in place of butyl group. These structural differences make it less lipid soluble resulting in less potency and less cardiotoxicity. Reduced lipophilicity renders difficulty in penetration of large myelinated motor fibers8,34. Some authors who were unable to detect appreciable benefit from single injection of local anesthetic35 reported that the ability to provide prolonged application of local anesthetic to wounds through a catheter is probably important20. Therefore continuous36 and/or intermittent infusion37 of the surgical wound with local anesthetic solution has been introduced as a way of extending local anesthetic induced incision pain relief in postoperative period38, with the introduction of new portable pumps can now be used on an ambulatory basis 39 with these catheter delivery system ,the risk of infection appears to be small. However bacterial colonization of the catheter is a common occurrence 40. Thus in future wound infiltration using catheter technique should be planned. Conclusion This study establishes the effectiveness of wound infiltration using local anesthetics(bupivacaine/ropivacaine) alongwith fentanyl as a part of multimodal analgesia for postoperative pain relief after total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy under spinal anesthesia. When bupivacaine or ropivacaine are used in similar dose and concentration for wound infiltration, bupivacaine seems to be more effective in decreasing pain scores and provided better satisfaction scores, however it could not affect rescue analgesic consumption. REFERENCES 1. Leong SB, Sia ATH. Postoperative pain management after abdominal hysterectomy. Journal of Pediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2011; 37(1): 5-12. 2. Dahl JB, Moinich S. Relief of postoperative pain by local anaesthetic infiltration: Efficacy for major abdominal and orthopedic surgery. Pain 2009; 143: 7-11. 3. Mehta TR, Parikh BK, Bhosale GP, Butala BP, Shah VR. Postoperative analgesia after incisional infiltration of bupivacaine v/s bupivacaine with buprenorphine. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2011; 27(2): 211-14. 4. Mehta TR, Parikh BK, Bhosale GP, Butala BP, Shah VR. Postoperative analgesia after incisional infiltration of bupivacaine v/s bupivacaine with buprenorphine. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2011; 27(2): 211-14. 5. Tverskoy M, Braslasky A, Mazor A, Ferman R, Kissin I. The peripheral effect of fentanyl on postoperative pain. Anesth Analg 1998; 87:1121-4. 6. Mostafa GM, Mohamad MF, Bakry RM, Farrag WSH. Effect of tramadol and ropivacaine infiltration on plasma catecholamine and postoperative pain. Journal of American science 2011; 7(7):473-79. 7. Fayman M, Beeton A, Potgieter E, Becker PJ. Comparative analysis of bupivacaine and ropivacaine for infiltration analgesia for bilateral breast surgery. Aesth Plast Surg 2003; 27:100-103. 8. Simpson D, Curran MP, Oldfield V, Keating GM. Ropivacaine: a review of its use in regional anaesthesia and acute pain management. Drugs 2005; 65(18): 2675-717. 9. Hannibal K, Galatius H, Hansen A, Obel E, Ellen E. Preoperative wound infiltration with bupivacaine reduces early and late opioid requirement after hysterectomy. Anesth Analg 1996; 83: 376-81. 10. Cobby TF, Reid MF. Wound infiltration with local anaesthetic after abdominal hysterectomy. Br J Anaesth 1997; 78: 431-32. 11. Mulroy MF, Burgess FW, Emanuelsson BM. Ropivacaine 0.25% and 0.5%, but not 0.125% provide effective wound infiltration analgesia after outpatient hernia repair, but with sustained plasma drug levels. Reg Anesth Pain Med 1999; 24(2):136-41. 12. Fredman B, Shapiro A, Zohar E, Feldman E, Shorer S, Rawal N, et al. The analgesic efficacy of patient-controlled ropivacaine instillation after cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg 2000; 91(6):1436-40. 13. Erichsen CJ, Vibits H, Dahl JB, Kehlet H. Wound infiltration with ropivacaine and bupivacaine for pain after inguinal herniotomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1995; 39(1): 67-70. 14. Buvanendran A and Kroin JS. Multimodal analgesia for controlling acute postoperative pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009; 22: 588-93. 15. Ashburn MA, Caplan RA, Carr DB. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on acute pain management. Anesthesiology 2004; 100:1573–81. 16. Zahid S. Effectiveness of wound infiltration with local anesthetic agent after abdominal surgery. JPMI 2007; 21(4):274-77. 17. Lavand’ homme PM, Roleants F, Waterloos H, Kock D. Postoperative analgesia effect of continuous wound infiltration with diclofenac after elective cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology 2007; 106 (6): 1220-5. 18. Shadangi BK, Garg R, Pandey R. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the analgesic efficacy of extraperitoneal wound instillation of bupivacaine and morphine in abdominal surgeries. Anaesth Pain and Intensive Care 2012; 16(2):169-73. 19. Ng A, Swami A, Davidson AC, Emembolu J. The analgesic effect of intraperitoneal and incisional bupivacaine with epinephrine after total abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg 2002; 95(1): 158-62. 20. Liu SS, Richman JM, Thirlby RC, Wu CL. Efficacy of continuous wound catheters delivering local anesthetic for postoperative analgesia: A quantitative and qualitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Surg 2006; 203(6): 914-32. 21. Givens VA, Lipscomb GH, Meyer NL. A randomized trial of postoperative wound irrigation with local anesthetic for pain after cesarean delivery. Am J Obstret Gynecol 2002; 186(6):1188-91. 22. Stein C, Schafer M, Machelska H. Attacking pain at its source: new perspectives on opioids. Nat Med 2003; 9(8):1003-8. 23. Stein C, Millan MJ, Shippenberg TS, Herz A. Peripheral effects of fentanyl upon nociception in inflamed tissue of the rat. Neurosci Lett 1988; 84: 225-8. 24. Boirkman S, Stanski M D, Verotta D, Harashima H. Comparative tissue concentration profiles of fentanyl and alfentanil in humans predicted from tissue/blood partition data obtained in rats. Anesthesiology 1990; 72: 86573. 25. Klein JR, Heaton JP, Thompson JP, Cotton BR, Davidson AC, Smith G. Infiltration of the abdominal wall with local anaesthetic after total abdominal hysterectomy has no opioid-sparing effect. Br J Anaesth 2000; 84(2): 248-9. 26. Cervero F. Visceral pain: mechanisms of peripheral and central sensitization. Ann Med 1995; 27:235-9. 27. Zohar E, Fredman B, Phillipov A, Jedeikin, Shapiro A. The analgesic efficacy of patient-controlled bupivacaine wound instillation after total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Anesth Analg 2001; 93(2):482-87. 28. Dahl J, Moiniche S, Kehlet H. Wound infiltration with local anaesthetics for postoperative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1994; 38:7–14. 29. Moinich S, Kehlet H, Dahl JB. A qualitative and quantitative systematic review of preemptive analgesia for postoperative pain relief: The role of timing of analgesia. Anesthesiology 2002; 96:725-41. 30. Al- hakim NHH, Alidreesi ZMS. The effect of local anaesthetic wound infiltration on postoperative pain after caesarean section. Journal of Surgery Pakistan 2010; 15(3):131-34. 31. Wallace MS, Dyck JB, Rossi SS, Yaksh TL. Computer-controlled lidocaine infusion for the evaluation of neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury. Pain 1996; 66: 69–77. 32. Woolf CJ, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. The systemic administration of local anesthetics produces a selective depression of C-afferent fibre evoked activity in the spinal cord. Pain 1985; 23: 361–74. 33. Zink W, Graf BM. The toxicity of local anaesthetics: the place of ropivacaine and levobupivacaine. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2008; 21:645– 50. 34. Kuthiala G, Chaudhary G. Ropivacaine: A review of its pharmacology and clinical use. Indian J Anaesth 2011; 55(2): 104-10. 35. Moiniche S, Jorgensen H, Wetterslev J, Dahl JB. Local anesthetic infiltration for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopy: A qualitative and quantitative systematic review of intraperitoneal, port-site infiltration and mesosalpinx block. Anesth Analg 2000; 90:899-12. 36. Gibbs P, Purushotam A, Auld C, Cuschieri RJ. Continuous wound perfusion with bupivacaine for postoperative wound pain. Br J Surg 1988; 75: 923-4. 37. Gupta A, Thorn SE, Axelsson K, Larsson LG, Agren G, Holmstrom B, et al. Postoperative pain relief using intermittent injections of 0.5% ropivacaine through a catheter after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg 2002; 95:450–6. 38. White PF. The changing role of non-opioid analgesic techniques in the management of postoperative pain. Anesth Analg 2005; 101 (5 Suppl): S5–S22. 39. Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Enneking FK. New portable infusion pumps: real advantages or just more of the same in a different package. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2004; 29:371-6. 40. Cuvillon P, Ripart J, Lalourcey L, Veyrat E, L'Hermite J, Boisson C, et al. The continuous femoral nerve block catheter for postoperative analgesia: bacterial colonization, infectious rate and adverse effects. Anesth Analg 2001; 93:1045–9.