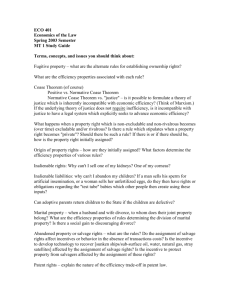

Other personal injury damages issues

advertisement

6 Other personal injury damages issues The terms of reference require the Commission to recommend options for the Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic) to operate more efficiently and equitably, consistent with the objectives of the tort law changes of the early 2000s. This chapter examines the following issues that were raised by stakeholders concerning the operation of the personal injury damages provisions of the Wrongs Act, namely: differences in the treatment of remedial surgery on spinal injuries arising from Mountain Pine Furniture Pty Ltd v Taylor (2007) 16 VR 659 (‘Mountain Pine’) the interpretation by the courts of the threshold regarding damages for costs of gratuitous attendant care by others whether the Wrongs Act should provide for an entitlement to damages for loss of capacity to care for others a particular inconsistency arising from the interaction of the Wrongs Act and the Transport Accident Act 1986 (Vic), whereby claims made under section 94 of the Transport Accident Act are not subject to the limitations on personal injury and death imposed by the Wrongs Act The Commission has focused on assessing options for reform in these areas against the principles of equity and consistency with the underlying objectives of tort law reform. Efficiency impacts, in terms of transaction costs or incentives to invest in safety are assumed to be negligible and thus are not discussed in detail. For example, providing a limited entitlement for loss of capacity to care for others is assumed unlikely to increase the number of claims — that is, increase transaction costs — or change incentives to invest in safety. Stakeholders also raised issues about the efficiency of the Medical Panels process. These are discussed in section 6.5. 6.1 Differences in the treatment of remedial surgery on spinal injuries The Wrongs, Accident Compensation and Transport Accident Acts take account of the effects of remedial surgery on spinal injuries differently. In 2007, amendments were made to the Accident Compensation and Transport Accident Acts in response to the Victorian Court of Appeal’s decision in Mountain Pine. The court reversed the Victorian WorkCover Authority’s (VWA) approach to the assessment of spinal injuries, ‘holding that workers should have their spinal injuries assessed prior to having surgery rather than after surgery’ (Victorian Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly 2007, 3125). The 2007 amendments omitted the following paragraph on the assessment of spinal impairments from the American Medical Association Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment (Fourth Edition) (AMA-4 Guides): With the Injury Model, surgery to treat an impairment does not modify the original impairment estimate, which remains the same in spite of any changes in signs or symptoms that may follow the surgery and irrespective of whether the patient has a favourable or unfavourable response to treatment. (AMA 1993, 3/100) OTHER PERSONAL INJURY DAMAGES ISSUES 79 In introducing these amendments the then Minister for Finance, WorkCover and Transport Accident Commission noted that the: … [Mountain Pine] decision threatens to create significant inequities among those Victorians supported by the [Transport Accident Commission] TAC and VWA schemes. It is not fair that a person whose spinal injury improves as a result of surgery be entitled to the same compensation as a person whose injury worsens as a result of the same treatment. (Victorian Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly 2007, 3125) No such amendments have been made to the Wrongs Act. That is, there is no requirement in the Wrongs Act that assessment of impairment of spinal injuries take into account the effect of any remedial surgery. 6.1.1 Participant views In supporting amendments to the Wrongs Act to make it consistent with the other personal injury Acts, the Australian Medical Association (Victoria) Ltd noted that: This situation has led to difficulties for Medical Panels when assessing spinal injuries as … Medical Panels must imagine the patient’s condition prior to treatment in order to determine the level of impairment. (sub. 17, 2) The Insurance Council of Australia also supported restoring the pre-Mountain Pine position, noting that making an assessment based on the likely level of impairment after treatment: … would also help remove the perverse incentive of not undertaking such treatment to maximise benefits. (sub. 14, 6) On the other hand, the Common Law Bar Association (CLBA) submitted that given claimants are unable to access a narrative test under the Wrongs Act (chapter 3), it would be unfair to amend the Wrongs Act in line with the Accident Compensation and Transport Accident Acts to overturn the Mountain Pine decision (sub 11, 8). The CLBA also noted that: … the Wrongs Act already requires that the injury suffered be stabilised. Provision is also made if 6 months pass since the first assessment, and the clinician is satisfied the threshold will be met once the injury has stabilised: s 28LNA. It is submitted that this is sufficient to ensure injuries are properly assessed, without limiting the ability of an assessor to use the [Diagnosis Related Estimates] DRE Model without having regard to surgery used to treat impairment: section 3.3(d) of the AMA Guides (sub. 11, 8). 6.1.2 Options The sole option for reform in this area is whether to amend the Wrongs Act to be consistent with the changes to the assessment of spinal injuries made to the Accident Compensation and the Transport Accident Acts in 2007 (see above). 80 ADJUSTING THE BALANCE: INQUIRY INTO ASPECTS OF THE WRONGS ACT 1958 6.1.3 Assessment Equity Amending the Wrongs Act to restore the pre-Mountain Pine position would improve horizontal equity by treating persons with similar spinal injuries in the same way under the three personal injury Acts. The current situation gives rise to potential inequities, whereby a person whose spinal injury improves as a result of surgery is currently entitled to the same compensation as a person whose similar spinal injury does not improve or worsens as a result of the same treatment. This amendment would address this vertical inequity. Consistency with the underlying objectives of tort law reform The AMA-4 Guides were first applied to the impairment assessment process under the Wrongs Act as part of tort law changes of the 2000s. Prior to this, the Guides were (and are still) used in the assessment of impairment for the purposes of the Accident Compensation and the Transport Accident Acts. The explanatory memorandum and the second reading speech for the Transport Accident and Accident Compensation Acts Amendment Bill indicate that it was long-standing convention under both the Accident Compensation Act and the Wrongs Act to assess impairment on the basis of the post-surgery condition. For example, the explanatory memorandum stated that the Bill was intended to: … codify the long standing practice in relation to the assessment of permanent impairment, including spinal impairment, prior to the decision of the Court of Appeal in Mountain Pine Furniture Pty Ltd v Taylor. (Victorian Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly 2007, 6) The Commission understands the intention in introducing the impairment assessment process into the Wrongs Act was to make the process similar to that applied under the Accident Compensation Act and Transport Accident Acts. For example, the second reading speech1 noted that: Honourable members will be familiar with the use of the AMA Guides, the psychiatric impairment guidelines and the hearing loss assessment procedures from their use since around 1990 in the WorkCover and TAC statutory compensation schemes. (Victorian Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly 2003a, 2078) In regard to impacts on the price and/or availability of public liability and professional indemnity insurance, the Law Institute of Victoria submitted that: … the likely impact of such an amendment would be to result in lower impairment assessments, since it is common that after a claimant has surgery to rectify or treat an injury, the impairment is lower. (sub. 13, 18) 1 Wrongs and Limitation of Actions Acts (Insurance Reform) Bill 2003 OTHER PERSONAL INJURY DAMAGES ISSUES 81 6.1.4 The Commission’s view The Commission’s understanding is that Parliament intended impairment assessment to be undertaken on the basis of a claimant’s post-surgery condition. The decision in Mountain Pine created a vertical inequity. Applying the amendments made to the other Victorian personal injury Acts in 2007 to the Wrongs Act would remove the inequity and restore the Parliament’s intention. The Commission returns in chapter 8 to the treatment of remedial surgery on spinal injuries in its consideration of a package of possible adjustments to the Wrongs Act. 6.2 Damages for costs of gratuitous attendant care by others Under common law, damages may be awarded as compensation for the need for an injured person to be cared for by friends and relatives without payment (Negligence Review Panel 2002, 199–200). These damages are known as damages for gratuitous attendant care or ‘Griffiths v Kerkemeyer’ damages.2 They ‘compensate the injured claimant for the claimant’s need for gratuitous services to be provided to the claimant because the claimant can no longer provide those services to him or herself’ (NSW Government 2006, 2). There is limited publicly available data on: the number of awards for gratuitous attendant care the average size of damages awarded for gratuitous attendant care. Wrongs Act provisions The tort law changes introduced in Victoria in the early 2000s imposed limits on damages for gratuitous attendant care. In 2003, the second reading speech 3 noted that: The purpose of limiting the power of the court to award damages [for gratuitous attendant care] is to limit excessive awards in these cases, particularly having regard to the fact that the plaintiff suffers no actual financial loss as the services are provided gratuitously. (Victorian Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly 2003a, 2082) Section 28IA(1) of the Act provides that damages are only available where: there is a ‘reasonable need’ for the care services the need has arisen solely because of the claimed injury and the services would not be provided to the claimant but for the injury The Wrongs Act also limits damages for gratuitous attendant care by precluding them if a certain threshold of care is not met. However, section 28IA(2) sets out this condition in different terms than those described by the then Premier (box 6.1), whereby no damages may be awarded if the services are provided, or are to be provided: 2 After Griffiths v Kerkemeyer (1977) 139 CLR 161. 3 Wrongs and Limitation of Actions Acts (Insurance Reform) Bill 2003. 82 ADJUSTING THE BALANCE: INQUIRY INTO ASPECTS OF THE WRONGS ACT 1958 (a) for less than six hours per week; and (b) for less than six months. Section 28IB also places a cap on damages that can be awarded for gratuitous attendant care, based on Victorian average weekly earnings (AWE) (or a pro-rata amount where services are provided for less than 40 hours per week). Court decisions In Alcoa Portland Aluminium Pty Ltd v Victorian WorkCover Authority (2007) 18 VR 146 (‘Alcoa v VWA’), the Court of Appeal held that s 28IA only precluded damages for gratuitous attendant care that was required for less than six hours per week and for less than six months (box 6.1) The effect of Alcoa v VWA is that the thresholds for eligibility operate alternatively rather than cumulatively, in which case a plaintiff would only be eligible where the two conditions are applied concurrently, that is, the care is required for six hours or more per week and for a period of six months or more. Similar judgments have been made in New South Wales (NSW) in the case of Harrison v Melhem (2008) 72 NSWLR 380 (‘Harrison v Melhem’), and in Queensland in the case of Grice v State of Queensland (2006) 1 Qd R 222. In 2008, in response to the decision in Harrison v Melhem, the NSW Parliament amended personal injury legislation to clarify: … that damages are to be awarded for gratuitous attendant care services only if the services are provided (or to be provided) for at least 6 hours per week and for at least 6 consecutive months. The amendment overcomes the effect of the Court of Appeal decision in Harrison v Melhem. (NSW Parliament 2008) Box 6.1 The implications of Alcoa v VWA In Alcoa v VWA, Alcoa argued that it was not necessary for both conditions of s 28IA(2) to be satisfied to preclude a claim. That is, Alcoa affirmed that the conditions should be read as alternatives, so that if either paragraph (a) or (b) were satisfied the claim would be precluded. Conversely, the Victorian WorkCover Authority argued that the conditions should be read cumulatively, given that the ‘ordinary and natural meaning’ of s 28IA(2) did not allow for an alternative reading of ‘and’ as ‘or’ (Alcoa’s position). Rather ‘and’ should be taken, consistent with its ordinary meaning, to require the sub-section to be read cumulatively. Alcoa argued in response that the true meaning of s 28IA was not its literal meaning but was to be found in the extrinsic materials, namely the Ipp report and the Second Reading Speech. The Victorian Supreme Court of Appeal found that the plain and literal meaning of ‘and’ prevails against any indication or expression of a contrary intention of extrinsic materials. The Court also did not accept that the words of a Minister could determine the meaning of a statute. Chernov JA said that the fact that the Premier ‘mis-described the operation of the provision and erroneously assumed that it was reflecting the … recommendation of the Ipp report is not to the point. Rather ‘what matters in the end is the language of Parliament’. The implications of the decision were that if a plaintiff requires care for at least six hours per week or for at least six months, his or her claim will not be precluded. Source: Commission analysis based on ‘Alcoa v VWA’. OTHER PERSONAL INJURY DAMAGES ISSUES 83 Relevant provisions in other Victorian personal injury Acts Both the Accident Compensation and Transport Accident Acts exclude common law damages for gratuitous attendant care. However, these Acts also provide for a no-fault system of ‘medical and like benefits’, which includes provision for costs of care by others. The Commission understands these statutory benefits are generally accessed by eligible plaintiffs prior to seeking common law damages. The limitations on these benefits are also substantially different from the limitations on gratuitous attendant care under the Wrongs Act. For example, under s 60 of the Transport Accident Act, rather than being provided for gratuitous services, benefits are only provided where a cost has been incurred for a home service; and, unlike the Wrongs Act, services must be performed by an ‘authorised person’. 6.2.1 Key issues Participants raised several issues concerning the limitations on gratuitous attendant care, including: the need for additional restrictions due to a perceived increase in speculative claims for gratuitous attendant care the need for the existing threshold and caps to restrict small claims for care services inequities for family members who care for catastrophically injured persons whether the time thresholds should operate alternatively or cumulatively (box 6.2). There is limited publicly available information on which to assess these issues. The Commission was, for example, unable to identify data on the number or size of awards for gratuitous attendant care under the Wrongs Act. It is likely, however, that such damages represent a significant component of damages for those claimants with severe injuries. The Victorian Managed Insurance Authority (VMIA) noted that damages for future care costs — which include both attendant and nursing care — comprise a large component of medical indemnity claims costs for catastrophic injury claims. For example, typically in catastrophic medical indemnity claims, the claim made for future care costs can be equivalent to a third of the total damages claimed (VMIA 2013). The Ipp report cited evidence that damages for gratuitous attendant care components represent ‘about 25 per cent of the total award in claims for more than $500 000’ (Negligence Review Panel 2002, 200). The Commission notes that the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) and the National Injury Insurance Scheme may impact on the award of damages for gratuitous attendant care for some persons (chapter 2). Given that the NDIS is currently not due for full rollout in Victoria until July 2019, and the lack of certainty about how both of these schemes will operate, the Commission has not taken into account the potential impacts of these schemes in its analysis. 84 ADJUSTING THE BALANCE: INQUIRY INTO ASPECTS OF THE WRONGS ACT 1958 Box 6.2 Participant views on gratuitous attendant care The Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV) submitted that in its experience, ‘claims for these damages are becoming more and more speculative and sizable’ (sub. 12, 15). The MAV argued that damages for gratuitous attendant care should be excluded under the Wrongs Act, or alternatively, access to such damages should be restricted to ‘the most severe cases of catastrophic injuries such as asbestos claims, quadriplegia, paraplegia and severe brain damage’ (sub. 12, 17). The Australian Lawyers Alliance (ALA) submitted that the cap on damages for gratuitous attendant care by others ‘unfairly disadvantages the families of catastrophically injured claimants, many of whom require 24 hour care, 7 days per week’ (sub. 9, 13-14). The ALA thus argued that the ‘cap on recovery for gratuitous care should be removed for claimants who require care for not less than 40 hours per week’, and that such an amendment would ‘only affect a small class of the most severely injured claimants: those most in need of care and support’ (sub. 9, 14). The Law Institute of Victoria submitted that the inquiry should clarify that the time thresholds are alternative not cumulative, in order to provide equitable outcomes for persons injured for less than six months but requiring extensive periods of care or periods of long term but low care needs (sub. 13, 9). In contrast, Avant Mutual Group Limited supported cumulative thresholds to restrict small claims for care services — such that services be required for six hours per week and for not less than six months — to restrict small claims for care services. Avant argued that ‘in many cases the costs of investigating the care claim is likely to outweigh the value of the potential damages.’ (sub. 16, 4). Source: Submissions to the inquiry. 6.2.2 Options To deal with the issues raised by participants, the Commission examined three options: (1) Restricting access to damages for gratuitous attendant care to the most severe cases of catastrophic injuries. (2) Removing the cap on gratuitous attendant care for catastrophically injured claimants. (3) Adopting the NSW approach, such that damages for gratuitous attendant care will be allowed if the care has been provided, or is likely to be provided, for at least six hours per week and for at least six consecutive months. That is, cumulative rather than alternative operation of the thresholds. 6.2.3 Assessment of options Consistency with the underlying objectives of tort law reform The available evidence suggests that the original intention of limitations on gratuitous attendant care was to: minimise transaction costs associated with smaller claims permit access to damages for gratuitous attendant care for injured persons who can demonstrate need arising from their injuries OTHER PERSONAL INJURY DAMAGES ISSUES 85 place a cap on the amount of gratuitous attendant care that can be awarded based on AWE, to facilitate access to affordable public liability and professional indemnity insurance (Negligence Review Panel 2002; Victorian Parliament 2003a). The Ipp report proposed that the thresholds for gratuitous attendant care operate cumulatively, so that eligibility depends on care being ‘provided for more than six hours per week and for more than six consecutive months’ (Negligence Review Panel 2002, 205). NSW, Queensland, Northern Territory and Tasmania have also adopted the Ipp report’s cumulative approach. Based on these considerations, option 3 (introducing a cumulative rather than alternative operation of the thresholds) would appear to be consistent with both the original intent of tort law changes, and the approach adopted in other jurisdictions. Equity All of the options for addressing concerns about the limitations on gratuitous attendant care would affect equity in one way or another. Horizontal equity requires similar levels of compensation for injuries of similar severity or care needs (chapter 1). The existing thresholds mean that persons with similar (but not identical) care needs, are treated differently. For example, one person with broken wrists may require care for five months and for five hours, whereas another person with a similar injury requires care for five months and six hours. Under the current test, the former would not be eligible for damages, while the latter would be. This inequity would be reinforced by moving to option 1 or option 3, as even more plaintiffs would be ineligible. Under option 1, a plaintiff can meet both tests and still be ineligible for compensation because their injury is not severe. Under option 3, for example, a plaintiff requiring care for six hours a week for seven months would remain eligible. However, a plaintiff requiring care for seven hours a week for five months, or five hours a week for seven months would no longer be eligible. Another horizontal equity consideration is consistency with the provisions of the other Victorian personal injury Acts. Given the other Acts provide for statutory benefits for care — and exclude access to common law damages — comparison across the Acts are of limited value. Vertical equity requires that persons with more severe injuries should receive higher levels of compensation than less severe ones (chapter 1). Option 2 would improve vertical equity by providing additional benefits to catastrophically injured persons, if the cap was undercompensating for their needs for gratuitous care. The other options would not impact vertical equity, given that those with more severe injuries would continue to receive higher levels of compensation. Due to the lack of available information on damages for gratuitous attendant care the Commission has been unable to assess the magnitude of the equity effects of the options. 86 ADJUSTING THE BALANCE: INQUIRY INTO ASPECTS OF THE WRONGS ACT 1958 Impact on price and availability of public liability and professional indemnity insurance As noted, damages awarded for gratuitous attendant care potentially comprise a significant proportion of claims costs and thus changes in the limitations have the potential to impact on the affordability and availability of public liability and professional indemnity insurance. Option 1 (restricting access to severe injuries) would see access to damages restricted to a small group of plaintiffs. In the first instance, this would reduce transaction costs and place downward pressure on insurance premiums. However, those persons denied access to damages for gratuitous attendant care may have a strong incentive to retain professional carers rather than family members to provide the services, perhaps leading to an increase in total damages awarded, and thus insurance premiums (Negligence Review Panel 2002, 201). Option 2 (removing the cap for catastrophic injuries) would result in additional benefits to a small group of plaintiffs. The Productivity Commission has reported that around 1000 people are catastrophically injured across Australia each year, with 11 per cent arising from medical incidents and 32 per cent from general injuries (PC 2011, 793). Assuming uniform distribution of injuries across Australia, this suggests around 250 people are catastrophically injured in Victoria, with about 40 per cent (or around 100) people suffering medical and general injuries — which would be likely to be covered by the Wrongs Act. If each of those people is assumed to have been injured as a result of the negligence of another and received additional (uncapped) damages for gratuitous attendant care of say $100 000, then there would be a $10 million impact on payouts. Thus, there is the potential for this option to have a significant impact on the price and/or availability of public liability and professional indemnity insurance. Option 3 (requiring thresholds to be cumulative) would be likely to result in fewer claims, as some claimants would be excluded by the cumulative threshold. This would place some downward pressure on insurance premiums, reduce transaction costs and bring Victoria into line with most other jurisdictions. 6.2.4 The Commission’s view The Commission’s preferred option is option 3 (requiring thresholds to be cumulative), as this option best reflects the original intention of the Ipp report recommendations. The Commission has not found data on how many people would be affected by this change, but would expect there would be some downward pressure on insurance claims and thus premiums. Of the other options considered: option 2 presents a risk of an unduly adverse impact on insurance premiums, given the potential for unlimited damages for gratuitous attendant care for some people option 1 may provide people denied access to damages for gratuitous attendant care with a strong incentive to retain professional carers, rather than family members to provide the services, potentially increasing damages awards. In turn, this could have a significant impact on insurance premiums. OTHER PERSONAL INJURY DAMAGES ISSUES 87 6.3 Damages for loss of the capacity to care for others Prior to a 2005 High Court of Australia decision (see below), a separate head of damages for loss of capacity to care for others (family members or dependants) was available at common law. These damages were paid as compensation for the ‘loss of capacity, rather than financial loss as such’ (Negligence Review Panel 2002, 205). Under s 28ID(a) of the Wrongs Act, no damages may be awarded to a claimant for any loss of the claimant's capacity to provide gratuitous care for others unless the court is satisfied that the care: was provided to the claimant's dependants was being provided for at least six hours per week and for at least six consecutive months before the injury to which the damages relate. Alternatively, s 28ID(b) provides that no damages may be awarded unless there is a reasonable expectation that, but for the injury to which the damages relate, the gratuitous care would have been provided to the claimant’s dependants: for at least six hours per week and for a period of at least six consecutive months. Section 28IE places a cap on the amount of damages that can be awarded for loss of capacity to provide gratuitous care. The cap is based on Victorian AWE.4 In the case of CSR Ltd v Eddy (2005) 226 CLR 1 (‘CSR Ltd v Eddy’), the High Court held that damages for the loss of capacity to care for others (also known as Sullivan v Gordon damages)5 should not be recoverable as a specific head of damages. The court also held that this type of damages should be part of an award for non-economic loss, reflecting the loss of amenity and enjoyment of life the plaintiff had derived from providing assistance (Hunt 2010, 3). To be eligible for damages for non-economic loss, a claimant under the Wrongs Act needs to meet the ‘significant injury’ threshold, and any damages are subject to a cap of around $500 000 (chapters 3 and 4). 6.3.1 Key issues A number of jurisdictions — NSW, Queensland, South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory — have enacted statutory provisions to partially restore the common law right to damages for loss of capacity to care for others (NSW Government 2006, 3). This reflects the view expressed by the High Court in CSR Ltd v Eddy that the legislature, rather than the courts, should determine whether and in what circumstances these damages should be awarded (Queensland Parliamentary Debates 2009, 2607). 4 Section 28IF also provides an exception from s 28ID and s 28IE for injuries resulting from dust related conditions or from smoking, use of tobacco products or exposure to tobacco smoke. 5 After Sullivan v Gordon (1999) 47 NSWLR 319. 88 ADJUSTING THE BALANCE: INQUIRY INTO ASPECTS OF THE WRONGS ACT 1958 Participant views Limited comment was received from participants on the issue of damages for loss of capacity to care for others. The Law Institute of Victoria submitted that the Wrongs Act ‘should be amended to clarify that the intention [of s 28ID] is to partially reinstate ‘Sullivan v Gordon damages’ in cases where the lack of such a head of damage would result in serious inequity to people injured or killed by negligent acts’ (sub 13, 9). The LIV also reported that its members encountered this issue only in rare cases (sub. 13, 18). Similarly, the ALA noted that: Section 28ID currently assumes the existence of this head of damages … The legislature sought to confirm the existence of this head of damages, as it would be unjust for recovery to be forbidden in appropriate cases. However, a balance was struck by creating a threshold requirement for recovery. (sub. 9, 14) Avant Mutual Group Limited supported the removal of s 28ID, noting that: Section 28ID purports to limit damages that are not available to the plaintiff at common law. The provision does not create a legal basis for damages for the loss of capacity to care for others. (sub. 16, 4) 6.3.2 Option The NSW reforms provide an example of how a limited entitlement to damages for loss of capacity to care for others could be implemented in the Wrongs Act. These reforms were designed to ensure that damages are payable in the cases of greatest need, such as in cases where the claimant was providing significant care — for at least six hours per week and for six consecutive months — for dependants with a physical or mental incapacity (NSW Government 2006). To achieve these objectives, s 15 of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) imposes limitations such that: there is a reasonable expectation that, if the claimant had not been injured, the claimant would have provided the services for at least six hours per week and for at least six consecutive months the claimant’s dependants must not be capable of performing the services themselves by reason of their age or physical or mental incapacity the services are needed and that need is reasonable in all the circumstances. 6.3.3 Assessment Equity Providing an entitlement to damages for the loss of capacity to care for others would address a potential inequity in that persons injured through no fault of their own would be entitled for the loss of their ability to care for family members and others. And if the damages were targeted to those with the greatest need, vertical equity would also be improved. The exact impact would depend on how many persons were eligible to access such damages. OTHER PERSONAL INJURY DAMAGES ISSUES 89 Consistency with the underlying objectives of the tort law reform While s 28ID of the Wrongs Act provides limitations on the amount of damages that can be awarded for loss of capacity to care for others, it does not provide a statutory entitlement for these damages. There is limited public information about the Parliament’s view about entitlement to these damages. For example, the second reading speech for the Wrongs and Other Acts (Law of Negligence) Bill stated that: The purpose of limiting the circumstances in which an award of damages may be made is to limit the number of claims for loss of capacity to provide care for others. The purpose of limiting the level of damages that may be awarded is to prevent excessive awards of damages for these types of claims. (Victorian Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly 2003b, 1428) Furthermore, the explanatory memorandum for the Bill noted that: Section 28ID(b) also provides that the court can award damages for loss of capacity to provide gratuitous care for others where there is a reasonable expectation that but for the injury, the gratuitous care would have been provided to the claimant's dependants for at least 6 hours per week and for a period of at least 6 consecutive months. (Victorian Parliament 2003b, 15) Taken together, the Commission considers it reasonable to conclude that the original intention of the reforms was to limit, but not completely deny, the availability of this type of damages at common law. Impacts on the price and/or availability of public liability and professional indemnity insurance Only limited information is available to assess likely impacts on insurance premiums. The LIV cited anecdotal feedback from NSW practitioners (solicitors and counsel) that claims for this head of damages were not common in the public liability and medical indemnity areas, and that ‘a flood of claims has not been observed’ (LIV correspondence). Modelling of the impact on public sector medical indemnity premiums of allowing damages for the loss of capacity to care for others found that: These damages could potentially be claimed for very significant periods, for example lifelong care for a family member that may be disabled. What the VMIA claims data does show is that future care costs paid to adults in claim settlements represents approximately 8% of total medical indemnity claim payments. On the basis of the VMIA modelling the upwards impact on premiums of introducing a statutory entitlement to Sullivan v Gordon damages could be in the order of magnitude of 5% to 10%. (VMIA 2013, 17) While it is difficult to extrapolate these results to the broader public liability and medical indemnity insurance markets, the findings suggest that allowing damages for the loss of capacity to care for others could place significant upward pressure on insurance premiums. 90 ADJUSTING THE BALANCE: INQUIRY INTO ASPECTS OF THE WRONGS ACT 1958 6.3.4 The Commission’s view The Commission considers there is a prima facie case to provide a limited entitlement to damages for loss of capacity to care for others, given the original intention of the reforms was to limit, but not completely deny, access to this type of damages. The NSW approach would appear to be a reasonable means of ensuring that this type of damages would be restricted to those most in need. However, the Commission does not favour implementing this option at this time, given uncertainty about the likely impacts on insurance premiums. The Commission seeks further information from participants about the likely impact of this option. Information request What are the likely impacts on the price and availability of public liability and professional indemnity insurance of adopting the NSW approach to provide a limited entitlement to damages for loss of capacity to care for others? 6.4 Inconsistency arising from the interaction of personal injury Acts 6.4.1 Context The Commission was advised of a particular inconsistency arising from the interaction of the Wrongs Act and the Transport Accident Act. This arose from the case of Hynes v Hynes (2007) 15 VR 475 (‘Hynes v Hynes’). In this case, the plaintiff brought a common law claim against the defendant for negligently removing the cap from the overheated radiator of his car, allowing boiling water to suddenly erupt and injure the plaintiff. Part VB of the Wrongs Act provides that some awards of personal injury damages are not subject to caps and discounts, including an award to which Part 3, 6 or 10 of the Transport Accident Act applies (s 28C(2)(b)). In addition, Part VBA provides that the Wrongs Act thresholds for recovery of damages for non-economic loss do not apply to certain claims, and these also include claims to which Part 3, 6 or 10 of the Transport Accident Act applies (s 28LC(2)(b)). 6.4.2 Key issues In Hynes v Hynes, the Court of Appeal held that the defendant was negligent and that the plaintiff’s claim for damages was not restricted by the thresholds, caps and discounts in the Wrongs Act by virtue of the exceptions in ss 28C and s 28LC. The defendant was indemnified by the TAC under Part 6 of the Transport Accident Act, which indemnifies owners and drivers of Victorian registered vehicles in respect of liability arising from use of the indemnified vehicle (s 94). This decision means that in situations where a person is injured through the negligent use of a motor vehicle the TAC is potentially liable to indemnify claimants for: small claims given that there is no threshold; and uncapped claims, however large. In addition, awards are not discounted as they are in other cases brought under the Wrongs Act (chapter 5). OTHER PERSONAL INJURY DAMAGES ISSUES 91 6.4.3 Option The option for reform would be to amend the Wrongs Act to ensure that claims made under s 94 of the Transport Accident Act are subject to the limitations of the Act. 6.4.4 The Commission’s view The decision in Hynes v Hynes appears to be inconsistent with the underlying intention of tort law changes to restrict access to common law rights for injured persons for personal injury incidents covered by the Wrongs Act. The Commission has also not found any policy reasons (for example, within Victorian Parliamentary debates or the Ipp report) to support an exclusion for these types of TAC claims for people who suffer personal injuries or death as a result of another person’s negligent use of a motor vehicle. The Commission is also not aware of any comparable liability in other Australian jurisdictions. In addition, from an equity perspective, the option for reform would improve horizontal equity, as it would mean that a person injured in incidents arising out of the use of a motor vehicle would no longer have access to uncapped damages. Rather, they would have the same rights as other Wrongs Act claimants. 6.5 Medical Panels processes Medical Panels are constituted pursuant to the Accident Compensation Act and the Wrongs Act. Medical Panels are a key part of Wrongs Act pre-litigation procedures that enable claimants and respondents to determine whether the significant injury threshold is met (chapter 3). Wrongs Act referrals to Medical Panels are made by respondents after being served with a Certificate of Assessment by a claimant (or a claimant’s representative). Figure 6.1 shows a stylised representation of the Medical Panels process. 92 ADJUSTING THE BALANCE: INQUIRY INTO ASPECTS OF THE WRONGS ACT 1958 Stylised representation of the Medical Panels process Claimant serves statement of claim on respondent. To support claim for non-economic loss, claimant provides prescribed information and Certificate of Assessment. Respondent takes decision to either: (a) Accept Certificate of Assessment or (b) Refer ‘medical question’ to Medical Panel. Respondent has 60 days in which to respond to claimant. Respondent can request more information from claimant within the 60 days. Where (b) occurs, respondent provides prescribed information, copy of Certificate of Assessment and medical question to the Medical Panels. Medical Panels require the medical question to be defined as ‘does the degree of impairment resulting from the injury to the claimant alleged in the claim satisfy the threshold level?’ (s 28LB). Convenor of Medical Panels decides whether to convene a Panel based on information provided in referral, including the medical question. Convenor may request: respondent to amend medical question to comply with s 28LB further documentation from the respondent (for example, medical records). If Medical Panel is convened, the Panel considers relevant medical information, including claimant’s medical history, to determine the incremental impairment. Medical Panel must disregard unrelated injuries or causes. Medical Panel may ask claimant to supply all documents in their possession that relate to the medical question; meet and answer questions; and submit to a medical examination. Medical Panel makes determination on whether the injury meets the ‘significant injury’ test. Source: Commission analysis. OTHER PERSONAL INJURY DAMAGES ISSUES 93 6.5.1 Number of Wrongs Act referrals From 2010–11 to 2012–13, the Medical Panels received 1377 Wrongs Act referrals. Of these referrals, 731 or around 55 per cent were categorised as ‘slips/trips and fall’, while 315 or around 25 per cent were medical-related claims for ‘failed or injurious treatment by practitioner or consultant’ (table 6.1). Wrongs Act referrals by type of event: 2010-11 to 2012-13 Type of event Number Percentage of all events (%) Slip/trip and fall 731 56 Failed or injurious treatment by practitioner or consultant 315 24 Impact by object 56 4 Care/custody/control 55 4 Traumatic event, witness or exposed to 39 3 Physical assault 27 2 Sport/recreation 19 1 Faulty product 15 1 Fire 14 1 Fall from height 11 1 Collapse of building/structure 10 1 Discrimination/harassment 10 1 Notes: A number of other categories had less than 10 referrals: abuse/molestation; accidental breakage; animal bite/attack; dog bite/attack; electric shock; environmental contamination or pollution; equipment breakdown; explosion and/or vibration; exposure to or contact with substance; faulty workmanship; impact by animal; impact or damage by vehicle; lifting; carrying or putting down objects; long term exposure to sound or noise; machinery use; negligent advice; other causes; other contamination; repetitive/overuse injury; subsidence/landslide; water. The following categories had zero referrals: asbestos; defamation/slander; excavation/drilling damage; exposure to sudden sound or noise; lease liabilities; mould; other financial loss; rusting/oxidation/discolouring; spray drift; trapped by machinery or equipment; weakening and/or removal of supports; welding; worker to worker injury. Source: Medical Panels correspondence. 6.5.2 Key issues Participants raised a number of issues with the Medical Panels process. For example, the MAV invited the Commission to consider whether the Medical Panels process ‘allows for the best decision to be made … [as] the current process does not ensure that the Medical Panel has all the relevant material before it to assist in its decision-making’ (sub. 12, 14). Norton Rose Fulbright and Wotton Kearney identified problems in relation to: the requirement for a claimant to provide prescribed information to a respondent the timing of Certificates of Assessment issued by claimants to respondents whether a Certificate of Assessment can bind multiple respondents (sub. 8; sub. 18). 94 ADJUSTING THE BALANCE: INQUIRY INTO ASPECTS OF THE WRONGS ACT 1958 Avant Mutual Group Limited also advocated that the Certificate of Assessment should: … be served before or at the time of serving the statement of claim, so as to give certainty to the defendants as to what head of damage the plaintiff will pursue. (sub. 15, 3) The LIV raised the issue of whether Medical Panels should be required to provide reasons for its decisions, consistent with the provisions of the Accident Compensation Act (sub. 13, 19). 6.5.3 The Commission’s view The terms of reference require that in making recommendations relating to personal injury damages, the Commission is to have regard to the possible impacts on Medical Panels and the courts. These impacts are relevant for provisions governing access to damages for non-economic loss. The Commission notes that in the absence of any changes to these provisions, the workload of Medical Panels is on an upward trend, and that additional claims could exacerbate this trend (chapter 3). Based on the processes outlined above, the Commission understands that in order to make an informed decision about whether a significant injury exists, the Medical Panels process relies upon: An initial assessment of the injury by an approved medical practitioner of whether the injury meets the threshold test. This is provided in the form of the Certificate of Assessment. The prescribed information provided by the claimant and the respondent related to the injury, including the description of the incident and details of the injury the claimant alleges to have suffered as a result of the incident. Complete and accurate medical information relevant to the claim, especially regarding unrelated or pre-existing injuries, including medical records, clinical and medical reports, reports of relevant tests and imaging, court documents/Statements of Claim and submissions. A medical question defined in a manner that allows the Panel to assess the incremental impairment from the injury, that is, to disregard unrelated (pre-existing) injuries or causes. The Commission identified a number of possible actions that could improve the operation of the Medical Panels process by reducing disputes about the referral and the problems of missing and incomplete information in referrals: (1) Placing the requirement on the claimant to identify all claimed injuries. (2) Requiring the respondent — when making a referral of the medical question — to base its referral on the information provided by the claimant regarding the nature of the claim and injury. The respondent would still be able to make a submission to the Panel about the claim. (3) Codifying the decision in Mitchell v Malios [2013] VSC 480, such that the Medical Panels would only be required to make a determination about the injuries assessed in the Certificate of Assessment. These proposed actions may be a relatively low cost means of improving the efficiency and equity of the Panels process. Wider policy and legal questions, such as the interaction of the Panels process with court proceedings, including the timing of the OTHER PERSONAL INJURY DAMAGES ISSUES 95 serving of Certificates of Assessments, and whether the Panels should provide reasons for their decisions, are outside the scope of the terms of reference. Information request 96 What if any, further actions need to be considered to assist the Medical Panels to make timely and accurate decisions? What would be the costs and benefits of these actions? ADJUSTING THE BALANCE: INQUIRY INTO ASPECTS OF THE WRONGS ACT 1958