Making: Undergoing not doing

advertisement

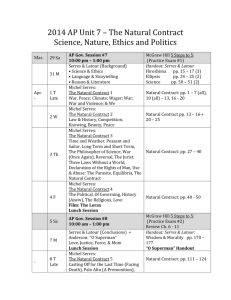

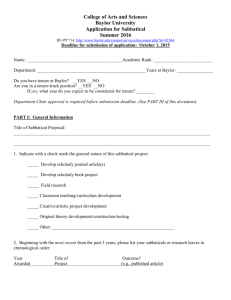

London Conference in Critical Thought 2015 The Politics and Practice of “Just Making Things” Proposal a for 20-minute presentation Making: Undergoing not doing If we accept that art objects are not knowledge artefacts [Scrivener, S. The art object does not embody a form of knowledge. Working Papers in Art and Design 2 (2002)] then what types of knowledge are generated through making and how is this knowledge shared without the art object being rendered as a by-product of a knowledge generation process? Addressing the problem from the standpoint of fine art education as a process of self-discovery, and as a practitioner currently on a research sabbatical, I propose to discuss the process of making as three distinct but entangled apprehensions. Form: Alertness. Being in the moment, attentive to the fabric and impression of the conditions and environment. Being human. Transformation: Understanding material. Enabling the evolution of an idea through responding to matter. Information: Acquiring experience from published knowledge. Finding a context. Making involves learning from a variety of different materials. ‘Just making things’ is disingenuous and lacks methodological focus. Making should open up perceptions of what is going on in our world so we can respond to it not just describe or represent it. This requires an understanding of an intermingling of the three apprehensions which are crucial to polymorphous nature of the environment of production: a sense of who, how, where, when and why, of undergoing not just doing. 221 words s.bennett@ed.ac.uk Stuart Bennett Deputy Principal Edinburgh College of Art University of Edinburgh EH3 9DF Intro Thank you for inviting me. I feel like an imposter – I have no PhD, I’m not studying for one, I’m a senior academic in an art college which recently merged with a research-intensive University. The University of Edinburgh has a rotational management model of either 3 or 5 years for senior roles and a sabbatical system that supports this. This presentation is a collection of thoughts and observations (not quite a case study) made between JanMay during my research sabbatical, as a response to the time and a tool for me to understand what I need to make the work I want make. Now I mean that very broadly, from the late 90s post educational turn perspective and as making as performance rather than representation, the materiality of art that cuts across and through language and produces, rather than represents, reality. The writing here that I will read, as I am a more seasoned maker than speaker, has been determined by the processes of conceiving and realising artworks. Works which, of course, cannot be presented here, as artwork should not be merely illustrative of the written text. Slide I was interested in the call for papers for this strand, which, unusually and thankfully, to my mind, did not make any use of the word ‘creative’. I’m keen to contest notions of intuition as a methodology of practice - often commonplace in art school education as an unspoken given. The justification of not knowing as a precedent to making, by extension, evades talking around the making process. It might be that by more clearly addressing the making of art we could find ourselves in a place of unknowing, a space of unlearning or rereading. More on this later but much of what follows arises out of and returns to material practice. Experiences, observations and reflexive understandings can help the analysis and interpretation of personal knowledge. The nature of making art is a critical process that accepts that knowledge and understanding constantly shift, methods flex and outcomes are often unexpected, yet possibilities are opened up for revealing what we don’t know as a means to challenge what we do know. It has been stated that thinkers can describe the ‘don’t know’ nature of making but the artists live it. This may be so but if artists can speak of living it, differently to critics, historians, sociologists, anthropologists etc would that not be beneficial within an educational context where making is at the core? To enable a sense of undergoing rather than doing for those that learn with us? Without some description of the ontological process of making there are gaps for false notions about the gift of creativity, the mythologising of the artistic process, the sense that we have to situate ourselves in a studio all day and night rendering our soul into a stream of meaningful images or objects. It is being aware of what the difference is that aids the understanding that making functionless objects, illusory images or ideational experiences is not different or other (or worse still creative and out there) but vital. Students need to be exposed to a range of positions and ideologies not just put in a studio and expected to create. Otherwise, as Abraham Maslow stated in the Psychology of Science; ‘It is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail’. Slide Telling Michael Polanyi comments in The Tacit Dimension that in all approaches to knowledge we need to start from the fact that 'we can know more than we can tell'. This pre-logical phase of knowing was for him 'tacit knowledge'. For Polanyi this was extensive. Riding a bike example. He stressed that all communication, everything we know about mental processes or feelings, all of our relationships to conscious intellectual activities, are based on a knowledge, which we cannot tell. What is not articulated remains untold and therefore tacit. "I learn through my hands, my eyes, and my skin what I can never learn through my brain.” — M.C.Richards But Tim Ingold asserts that in both its senses - the verbal relating of stories and the combination of sensory awareness with material variations telling is a practice of correspondence. At a personal level, knowing and telling are one and the same. Ways of knowing that grow through the experience of being does not commit those of us who make to silence in a forum like this one. I can tell you all I know. Just don’t expect me, without great difficulty and potential loss of meaning, to be able to articulate it. (un)Knowing, (re)Reading Ideas and places are similar as they need to be revisited as some experiences are only realised retrospectively. Similarly as Terry Eagleton stated; a poem can only be reread not read as some of its structures can only be perceived retrospectively. Which is of course true of encounters with art works – significance for the viewer happens after the event through experience and contemplation, long after the artist has finished making the work. Perhaps this is an entirely obvious statement but one that, in the culture of academic research, sits as an uncomfortable truth to the discipline. As an artist working in academia there is another responsibility I think. In some respect our job is to receive messages, to translate messages, and to send messages framed in terms of transmission and communication. Michel Serres gives a good example of ethics using the trope of the angel to understand communication. He said in an interview with the writer Hari Kunzru; (quote) I am a professor, and when I give a lecture, in the beginning I am Michel Serres, I am the real person who speaks. I must make a seduction for my students. I may begin with a joke, for example. After that I must disappear as a person on behalf of the message itself. The problem of disappearing as myself, to give way to the message itself, is the ethics of the messenger. HK: So you reduce your own subjectivity? MS: Yes, the reason why angels are invisible is because they are disappearing to let the message go through them. Slide 3 Perhaps artists make things so they don’t need to be present at all – the message goes through the transistor that is the object, image, experience of the work, the assertion of making, and implants itself on the intellect of the viewer hoping to leave some kind of latent residue. Serres’ first point was to understand and to clarify our jobs in a practical way, avoiding the spiritual problems but speaking about logical problems or practical problems. The problem of good and evil for instance is very easy to explain when you see that the messenger or channel is neutral, and on a neutral channel you can say I love you or I hate you, that’s good or that’s bad, I like it or I don’t like it. To describe our work is as communicators and message bearers Serres uses a history of labour. MS: There are three steps. In the beginning our ancestors were working with physical energies, with the body, with their muscles, as peasants. Like the caryatids who supported Greek temples, or Atlas, who carried the sky on his shoulders? These are figures of the first type of work. The second step is transformation of metals by engines and machines the industrial revolution. He uses three words that he states are the same word - form, transformation and information - the three steps. In the first step this form was solid as a statue. Atlas, the caryatid. In the second it is involved that the metal becomes liquid. In the third step we are living in the volatile transmission. This word volatile is angelic form. The transmission of message, of code, of signal is volatile. We say now about money that it is volatile, it is turning into the transmission of codes, of messages. (Mark McGowan the artist taxi driver speaks to this well but doesn’t articulate it.) Slide There are known knowns, there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns the ones we don’t know we don’t know. Donald Rumsfeld 2002 at a press briefing where he addressed the absence of evidence linking the government of Iraq with the supply of weapons of mass destruction to terrorist groups. It is interesting to note how close this is to Abraham Maslow, oft quoted by self-help gurus and leadership trainers and the man I quoted earlier who hoped we could equip students with more than a hammer. He proposed that there were four stages of learning. The final one may correspond notions of tacit knowledge and Rumsfeld’s first point – an odd coupling. Maslow identified (1) unconscious incompetence (lack of all recognition), (2) conscious incompetence, (recognition of some deficit), (3) conscious competence (an ability to do something with concentration and effort), and (4) unconscious competence (where something is so habitual that it can be performed effortlessly). The problem is that the person in possession of that highest level of competency may not be able to teach it (although this is perhaps not a problem as teaching effortlessly from habit is, I would argue, leaden and saturnine). Instructions on this level may only make sense to those who already know. Guidance from those at the highest level needs to survive in memory or in some other form until the student has reached that level. That may be why a teacher's remark, made many years before, has increased impact long after the encounter. Rereading and the alienating intimacy of the personal experience of making is well articulated by Mieke Bal. She talks of placing art first before influence, context, iconography, and historical lineage. How can we do an artwork justice of being an artwork and also learn from it as a theory on and example of thought about art? And how can the often solitary nature of making, that alienating intimacy, be made less peculiar as an experience while maintaining its insight? Slide Sabbatical From Jan-May this year I was released from teaching and administration to focus on research. In my sabbatical application I stated that I am interested in how art, primarily location specific sculpture and drawing, articulates and occupies space, its presence and separateness from other entities, how it touches and inhabits the fabric of our environment and constructs the space around itself. I said I would do this through considering latent histories of sites and materials in the process of researching and making the work. Recent exhibitions have focused on pared back and primitive technologies for drawing ‘accuracy’ – wooden templates, a brass polygraph, plumb lines. These works explore approaches to preciseness and use the fabric of the exhibition space as surface. Much of this is still pertinent but what sprung from the time was the intermingling of going places and experiencing things that made me realise other things. Walking a lot. Being in places and thinking about being there. Then reading around the things I was doing in a fairly scattergun manner. Having time to not just make things but to consider a more holistic approach to how I work which is naturally intertwined with how I live. Slide Tim Ingold speaks of going for a walk, you prepare, put on your specialist gear, prepared for the terrain but anything can happen. We need to find a correspondence with that environment. To think of longing – a sense you long for places, things or situations but you don’t know what they are. To think of a forward way of understanding the artistic process rather than working back from an object which is an abduction or a sense of detectivism and misses out the form generating possibilities of the material. To really understand this we need to follow how artists work, move upstream and become the criminal not the detective. To describe any material is to pose a riddle, this gives the material a voice and allows it to tell its own story. Or as Maria Fusco has stated; (quote) ‘Re-imagining the art object as sharing a number of basic ontological qualities with the riddle, I am interested in thinking through some ways to write about, or, again, write around the art object: to elicit, to unlock, to induce its essential obscurity with essential obscurity.’ (unquote) And I wonder if we can elicit an education in attention, an exposure to being prepared and unprepared simultaneously. To be engaged in what something might be rather than what it is. To see where action without agency would lead? Seek an attunement to being passive. To act in the middle voice, in a level register. To find a counterpoint. To be antidisciplinary. Can we create ordinary things as ordinary as the world? Slide then slide Summary It’s probably clear from this presentation that the senses of latency and inexactitude are still relevant if not now more prevalent. Perhaps there is more potency than latency now in the undergoing of the making process. There is definitely more attention to the slippage between the material of language and object and a helpful rupture in my own perceptions of theory and practice. And an articulation of how we make results in objects as apprehensions to be grasped not understood. Vitally I hope it speaks of, tells, perhaps even occasionally articulates, the need for those who make to speak of, tell, talk through the unfolding process of making. Art must provide grounds for its own interpretation. Writing does not supplant making but possesses an assertion or thinking internal to it as part of its divulgence and continuation of the conditions of its form. The detached affinity of personal experience through making writ large, shared and not left to mythological conjecture or conventional deduction. Slide Conclusion Serres stated: (quote) nous ne sommes pas intellectuels, je suis artisan. I think the job of a writer is a manual job. In the morning I write with my hands. I think the body is the subject of writing, really the body. My experience of writing is not an intellectual experience. It is a bodily experience. I feel myself as a manual worker. The relationship between the writer and his page - do you know that the origin of the word page is pagus the Latin name for the field where the peasant ploughs the earth. Peasant, pagus, page exactly the same thing. When you write you are ploughing a furrow. It is exactly the same labour. JF: It sets up the same oppositional relationships between the ploughed field and the nomadic hunter-gatherer, and writing versus speech. MS: yes it is possible that writing is ploughing whereas speaking is nomadic. As I am more adept at making than speaking, today I have been driving the tractor that pulls my plough. I look forward to being more nomadic during the Q&A. Thanks for your time. Slide what types of knowledge are generated through making? how is this knowledge shared without the art object being rendered as a byproduct of a knowledge generation process? Mention apprehension and grasp in relation to telling? And then talk about research sabbatical and the nature of this presentation (or correspondence) as a telling or retelling (with slippage) of some of my thinking through making/making through thinking etc. fine art education as a process of self-discovery Ingold. Unfolding. research sabbatical Case study. What I thought I would do. Cheval de frise. What I did. What I thought about. How that developed. What came out of it in relation to fine art education as a process of self discovery…. Daily routine. Walking. three distinct but entangled apprehensions. Form: Alertness. Being in the moment, attentive to the fabric and impression of the conditions and environment. Ingold. Heidegger. Philosophy of walking Neitzche. Transformation: Understanding material. Enabling the evolution of an idea through responding to matter. STONE. Ingold. Smithson. Information: Acquiring experience from published knowledge. Finding a context. Serres, Elizabeth Price and Deller. PhD and no practice degree 2012. Place based arts. Jessica Worden (Brunel) her work and research is concerned with the page as a site of performance that can be activated through live readings where page-based writing functions as a performance score. respond to it not just describe or represent it art making as a performance not as representation. Ontology. Tactility. Image of work made in Estonia undergoing not just doing summary to outline the issues raised above and how they could be articulated I read an interview in the journal Lire in which you say. Is this a rejection of your angelic status? MS: I am in contradiction. A good question. In this question I described my job HK: Here's a question about the difference between French intellectual culture and Anglo-American intellectual culture. In France you can write a book like Angels, which is a highly poetic book, a highly literary book, and it will be accepted as being a work of value to people working in both the arts and sciences, whereas in the intellectual tradition of Britain and America there is this division between the two. The type of writing which is acceptable to the scientific community is one very specific type of writing, and anything which smacks of the poetic is antagonistic to their idea of truth. So how would you defend yourself to a British scientist, and say my work is of value for you to understand communication? MS: I have two answers. The first one is I think that we have in France a very old tradition of linkage between science and philosophy. It was the case in the eighteenth century with Rousseau, Diderot, with Voltaire, with the Newtonian and novel writer and so on. But this link has not been functional for a century, because the problem's second answeris not the difference between French and AngloSaxon traditions, it is the difference between university and nonuniversity. The problem you're asking about is the tradition within the university, because there you are divided by department and speciality and so on. It is very difficult to put a link between science and philosophy, science and literature and so on. But in France, the philosophical tradition is out of the university. Why? Because in the university they spoke Latin, and philosophers spoke French. The difference was fundamental for the French tradition. Latin disappears around the middle of the nineteenth century. For instance, Bergson (the intuitive master) wrote his thesis in Latin HK/JF : No way! MS: In the beginning of the twentieth century! On Aristotle's theory of space [H. Bergson, Quid Aristoteles de loco senserit (Paris: Félix Alcan, 1889) - hk] HK: So the reason that the French tradition in which you stand is so hybrid, so mixed, is that it's a vernacular tradition, highly separate from this academic, scholastic tradition. Gros. Philosophy of walking. As a philosopher, his interest is in "ordinary things", he says. In Britain, academic philosophy is, largely, analytical philosophy. It's concerned with logic, with language. Whereas in France, he belongs to "a new generation that is concerned with the… quotidien. The everyday." Conclusion art making is undertaken in order to create apprehensions (i.e., that is objects that must be grasped by the senses and the intellect) which when grasped offer ways of seeing the past, present and future, rather than knowledge of the way things were or are. Hence, in the context of making art I would define research as original creation undertaken in order to generate novel apprehension. To finish, as Serres would begin his lecture, with a joke courtesy of Antony Hancock from the film The Rebel "Ladies and gentlemen, I shall now bid you all good day. I'm off! I know what I was cut out to do and I should have done it long ago. You're all raving mad! None of you know what you're looking at. You wait 'til I'm dead, you'll see I was right!" “In visual experience, which pushes objectification further than does tactile experience, we can, at least at first sight, flatter ourselves that we constitute the world, because it presents us with a spectacle spread out before us at a distance, and gives us the illusion of being immediately present everywhere and being situated nowhere. Tactile experience, on the other hand, adheres to the surface of our body; we cannot unfold it before us, and it never quite becomes an object.” — Maurice Merleau-Ponte The Phenomenology of Perception Heidegger suggests that "man dwells poetically," i.e., man's relationship to the world is one that is constantly in flux, never capable of being grasped in its totality. The poetic thinker never attempts to escape his environment in order to think; rather, the poetic thinker locates himself in the muck.