Misanthropy, Idealism, and Attitudes About Animals

advertisement

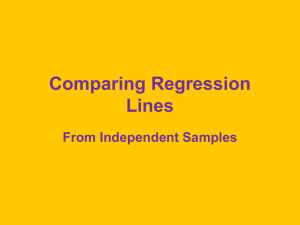

MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 1 Misanthropy, Idealism, and Attitudes Towards Animals Karl L. Wuensch, Kevin W. Jenkins, and G. Michael Poteat East Carolina University Author Note Karl L. Wuensch, Department of Psychology; Kevin W. Jenkins, Department of Psychology; G. Michael Poteat, Department of Psychology. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Karl L. Wuensch, Department of Psychology, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27858-4353. Electronic mail may be sent to WuenschK@ECU.edu. This manuscript was submitted for consideration for publication way back in 2002, to a journal that does not use APA style. I have reformatted it to serve as an example of a short APA-style manuscript. I have annotated it various notes, in this purple font. MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 2 MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 3 Abstract When evaluating the ethical status of an action that harms a nonhuman animal, one might weigh the benefit to humankind against the cost of the harm done to the nonhuman. To the extent that one does not like humans (is misanthropic), one will not be likely to think that benefits to humans can justify doing harm to nonhumans. We hypothesized that misanthropy would be less strongly related to support for animal rights among idealists (who tend not to do cost-benefit analysis) than among nonidealists. College students (N = 154) completed a questionnaire which included questions designed to measure their ethical idealism (10 items), misanthropy (5 items), and attitude towards animal rights and animal research (28 items). Respondents were classified as being idealistic if their score on the idealism scale was greater than the median score. The regression lines for predicting attitude towards animals from misanthropy differed significantly between idealists and nonidealists. Among nonidealists there was a significant positive relationship between misanthropy and support for animal rights, but among idealists the regression line was flat. Keywords: animal rights, attitudes, cost-benefit analysis, ethics, ethical idealism, misanthropy MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 4 Misanthropy, Idealism, and Attitudes About Animals In the last ten to twenty years the issue of animal rights has received considerable attention from the popular media in the United States and Europe. Animal rights advocates have demonstrated, legislators have passed new laws designed to protect nonhuman animals, comedians have made numerous jokes about hunters, fishers, and animal rights activists, and researchers have conducted polls about attitudes towards animals and animal rights. Professional organizations like the Animal Behavior Society and various medical and psychological organizations have studied the problem, revised policy statements, and attempted to persuade the public that animal research is necessary and can be conducted in a humane fashion. Twenty years ago it would be a rare person who had ever heard the phrase "animal rights." Today it is a rare person who has not, but there is not any strong consensus among the general public with regard to what sort of rights, if any, should be granted to nonhuman animals. In a national poll conducted just a few years ago (Balzar, 1993), respondents were nearly equally divided with respect to accepting or rejecting statements such as "Animals are just like people in all important ways." MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 5 Social psychologists have a history of studying the determinants of differences in attitudes involving issues that receive great attention among the general public, such as attitudes about race, sexuality, gender, abortion, etc. In the past few years differences in attitudes about animals and animal rights have been studied. Can we understand why some people support animal rights and others do not? What characteristics of an individual could we use to predict whether he or she is or is not a supporter of animal rights? Several researchers have reported that women are more likely than men to advocate animal rights and oppose animal research (Gallup & Beckstead, 1988; Herzog, Betchart, & Pittman, 1991; Plous, 1991, 1996a, 1996b; Driscoll, 1992; Galvin & Herzog, 1992a, 1992b; Broida, Tingley, Kimball, & Miele, 1993; Wuensch & Poteat, 1998; Herzog, 1999). [Notice that the order of citations, within parentheses, is alphabetical, not chronological] Attitudes about animals and animal research have been reported to be associated with age, pet ownership, religious affiliation, major in school, sex role orientation, political conservatism, vegetarianism, empathy towards animals, and attitudes about the environment, the military, and science (Gallup & Beckstead, 1988; Driscoll, 1992; Broida et MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 6 al., 1993). [ The second citation was given earlier, so should use the “et al.” notation.] Forsyth’s (1980) Ethics Position Questionnaire (EPQ) has played a central role in several recent investigations of attitudes about animals. The EPQ measures two ethical dimensions, idealism and relativism. People who score high on the idealism dimension believe that ethical behavior will always lead only to good consequences, never to bad consequences, and never to a mixture of good and bad consequences. People who score high on the relativism dimension reject the notion of universal moral principles, preferring personal and situational analysis of behavior. Early research with the EPQ showed ethical ideology to be associated with attitudes towards a variety of controversial issues, including homosexuality, abortion, euthanasia, sex outside of marriage, and attitudes about the ethics of social psychological research (Schlenker & Forsyth, 1977; Forsyth, 1980; Forsyth & Pope, 1984; Singh & Forsyth, 1989). More recently, support for animal rights and disapproval of animal research has been shown to be positively associated with idealism, and negatively (but weakly) associated with relativism (Galvin & Herzog, 1992a, 1992b; Wuensch & Poteat, 1998). Students’ evaluations of the effectiveness of anti-animal research literature have also been found to be MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 7 significantly affected by their gender and idealism (but not relativism) (Nickell & Herzog, 1996). In the battle to win the support of the public, animal rights advocates argue that humans can thrive without engaging in activities that cause suffering by animals, and animal use advocates argue that the suffering by animals is little and is justified by the benefit to humankind that results from research on and other use of animals (Miller, 1985; Tannenbaum & Rowan, 1985; Driscoll & Bateson, 1988; Dewsbury, 1990; National Academy of Sciences, 1991; Ulrich, 1991). Information about the amount of suffering by animals and the magnitude of the benefit to humankind is the sort of data people would need if they made moral decisions by doing a cost-benefit analysis, deciding that an action is ethical if its good consequences outweigh its bad consequences. Many people do engage in such cost-benefit analysis when deciding whether or not a particular use of animals is morally correct (Galvin & Herzog, 1992b; Herzog, Rowan, & Kossow, 2001), but some do not. Idealists believe that a morally correct action never leads to any bad consequences, so they do not engage in cost-benefit analysis -- if an action has any bad consequences, they consider it morally incorrect, regardless of any concomitant good consequences. MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 8 The ethical cost-benefit analysis we have described so far assumes that benefit to humankind is a good consequence, but some persons may not think highly enough of humans to feel that benefit to humankind is really much of a good consequence. To the extent that one does not like humans (is misanthropic), one should not be likely to think that benefits to humans can justify doing harm to animals. Accordingly, misanthropy is expected to be associated with support for animal rights in those persons (nonidealists) who do cost-benefit analysis when evaluating the morality of using animals. On the other hand, misanthropy should not be related to support for animal rights in idealists, since idealists do not engage in such ethical cost-benefit analysis. The purpose of the research reported here was to investigate the relationship between misanthropy and attitudes towards animals as moderated by idealism. We hypothesized that misanthropy would be less strongly related to support for animal rights among idealists than among nonidealists. Method College students in introductory general psychology (N = 154) completed a questionnaire which included items designed to measure their ethical idealism (10 items from D. R. Forsyth’s Ethics Position MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 9 Questionnaire), misanthropy (5 items), and attitude towards animal rights (28 items). Most of the participants identified themselves as white (88%) women (81%) under 20 years of age (88%) in their first year of college study (78%). All questionnaire items (other than those related to demographics) were statements with a Likert-type five-point response scale of agreement. For each scale, the mean response across items was computed for each respondent. Reliability for these instruments was estimated using maximized lambda4, which has been shown to be more consistently accurate than Cronbach’s alpha and other internal consistency reliability coefficients (Osburn, 2000). When the number of items was fewer than 10, maximized lambda4 was computed exactly. When the number of items was 10 or more, in which case computing the exact maximized lambda is unreasonably difficult, an approximation was computed (Callender & Osburn, 1977; Osburn, 2000). Reliability was .83 for the idealism scale, .78 for the misanthropy scale, and .93 for the animal rights/animal research scale. The animal rights scale and the misanthropy scale are presented in the appendix. You will also find there descriptive statistics for each of the scales used in the current study. Typical items on the idealism scale are: MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 10 “The existence of potential harm to others is always wrong, irrespective of the benefits to be gained,” and “deciding whether or not to perform an act by balancing the positive consequences of the act against the negative consequences of the act is immoral.” Respondents were classified as being idealistic if their score on the idealism scale was greater than the median score (3.7). Results Ignoring idealism, there was a small but statistically significant correlation between misanthropy and support for animal rights, r = .22, p = .006, 95% CI [.06. .37]. Regression analysis was employed to test the prediction that misanthropy would be less strongly related to support for animal rights among idealists than among nonidealists. A simultaneous test of slope and intercept indicated that the regression lines for predicting animal attitude from misanthropy differed significantly between idealists and nonidealists, F(2, 150) = 3.62, p = .029. The interaction between idealism and misanthropy was significant, t(150) = 2.25, p = .026, indicating that the slopes of the two regression lines differed (steeper for nonidealists than for idealists -- see Figure 1). The regression lines’ intercepts also differed significantly (higher for idealists), t(150) = 2.58, p = .01. MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 11 Support for Animal Rights 3 2.8 idealist nonidealist 2.6 2.4 2.2 2 1.8 1 2 3 4 Misanthropy Figure 1. Relationship between misanthropy and support for animal rights among idealists and nonidealists. When submitting a manuscript for consideration for publication, APA wants you to put figures and tables at the end of the manuscript. I want you put each figure or table in the body of the manuscript as near as possible to your first reference to the figure or table. You may need to enter a page break and put the table or figure on the page after first reference to it. Among nonidealists (n = 91), support for animal rights was significantly related to misanthropy, animal rights = 1.63 + .3 misanthropy, r = .36, p < .001, 95% CI [.17, .53] When corrected for attenuation due to lack of perfect reliability in the variables, the r = .42. Among idealists (n = 63), the regression line was flat, animal rights = 2.40 + 0.02 misanthropy, r = .02, p = .87, 95% CI [-0.23, +0.27]. MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 12 Regression diagnostics were used to determine if the regression lines obtained in our analysis were unduly influenced by a few outliers. Studentized deleted residuals were distributed as would be expected given a normal error term -- only 5% had values greater than 2. Cook’s D statistic was used to identify observations which had great influence on the regression analysis. For the df in our analysis, one would consider any observation with D > .7 to be one which had a large influence on the results of the regression analysis. There were no such observations. The largest value of D was .27, and 96% of the observations had D < .1. Discussion The idea to investigate an association between misanthropy and support for animal rights came to the first author (who was trained as a comparative psychologist but no longer is involved in research on nonhumans) after watching the evening news on television. The first part of the news had cast humankind in such a bad light that he was feeling quite misanthropic when they covered an animal rights protest. He found himself agreeing even more than usual with the protesters, and, in an attempt to explain that, decided it must be due to misanthropy. The idea of an association between misanthropy and support of animal rights has, however, occurred to others too. French (1975, p. 390) noted that in MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 13 Victorian England some persons considered the antivivsectionists to have "loved animals in proportion to their dislike for humans." More recently, Herzog (1998) wrote "animal activists are frequently dismissed as antiintellectual misanthropes who prefer kittens to sick children." Our initial (unpublished) attempts to detect an association between misanthropy and support of animal rights failed. Then we heard Hal Herzog speak about his research with the idealism variable, and we realized that not all persons engage in ethical cost-benefit analysis. In view of that, we set out to test the hypothesis that the expected association between misanthropy and animal rights would be found only among those who are not idealists. Our currently reported results do show that misanthropy was associated with support for animal rights, but only among nonidealists. Idealists believe that ethically correct behavior never leads to bad consequences, so they tend to be supporters of animal rights, since human use of nonhuman animals so often involves harming the animal, a bad consequence -- but idealists do not do ethical cost-benefit analysis, so whether they are misanthropic or not is unrelated to their support of animal rights. Nonidealists, on the other hand, do conduct ethical cost-benefit analysis. If they value humankind, they may decide that the costs of MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 14 animal use and animal research are justified by the benefits to humankind. Accordingly, they are not strong supporters of animal rights. Misanthropic nonidealists discount the value of benefits to humankind (or maybe even consider them of negative value), and thus cannot justify animal use to benefit humankind. Consequently, they are supporters of animal rights. French (1975, p. 390) provides an extreme example of misanthropy in the well known antivisectionsist Anna Kingsford, who, when explaining why she attended medical school, wrote: “I do not love men and women. I dislike them too much to care to do them any good. They seem to be my natural enemies. It is not for them that I am taking up medicine and science, not to cure their ailments, but for the animals and for knowledge generally. I want to rescue the animals from cruelty and injustice, which are for me the worst, if not the only sins. And I can’t love both the animals and those who systematically mistreat them.” When Dr. Anna Kingsford considered the morality of using animals to benefit humankind, we can assume that she greatly discounted any benefit to humankind. It should be noted that the results of the currently reported study do not address the question of whether or not animal rights activists are MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 15 misanthropic. Animal rights activists have been shown to be idealistic (Galvin & Herzog, 1992a), and misanthropy has now been shown not to be related to support for animal rights among idealists, suggesting that misanthropy might not be an important dimension for explaining the attitudes about animals held by animal rights activists. Whether the typical animal rights activist is misanthropic or not can only be determined by study of such activists. If one were to consider valuing the lives of nonhumans more than the lives of humans to be an indicator of misanthropy, then there is some evidence of more frequent misanthropy among activists (7%) than among nonactivists (0%) (Plous, 1991). MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 16 References Balzar, J. (1993, December 25). Creatures great - and equal? Los Angeles Times, pp. 1, 30, 31. [Newspaper article] Broida, J., Tingley, L., Kimball, R., & Miele, J. (1993). Personality differences between pro- and anti-vivisectionists. Society and Animals, 1, 129 - 144. [Journal article. Note use of ampersand instead of “and.”] Callendar, J. C., & Osburn, H. G. (1977). A method for maximizing and cross-validating split-half reliability coefficients. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 37, 819 - 826. Dewsbury, D. A. (1990). Early interactions between animal psychologists and animal activists and the founding of the APA Committee on Precautions in Animal Experimentation. American Psychologist, 45, 315 - 327 Driscoll, J. W. (1992). Attitudes toward animal use. Anthrozoös, 5, 32 39. Driscoll, J. W., & Bateson, P. (1988). Animals in behavioral research. Animal Behaviour, 36,1569 - 1574. Forsyth, D. R. (1980). A taxonomy of ethical ideologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 175 - 184. Forsyth, D. R., & Pope, W. R. (1984). Ethical ideology and judgments of social psychological research: Multidimensional analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 1365 - 1375. [Order in reference list is alphabetical by authors’ names, and “Forysth” comes before “Forsyth & Pope.” If there are two or more with the same authors, use chronological order, earlier dates first.] French, R. D. (1975). Antivivisection and medical science in Victorian society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Book. Notice that only the first word and the proper adjective start with upper case.] Gallup, G. G., Jr., & Beckstead, J. W. (1988). Attitudes toward animal research. American Psychologist, 43, 474 - 476. MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 17 Galvin, S. L., & Herzog, H. A., Jr. (1992a). Ethical ideology, animal rights activism, and attitudes toward the treatment of animals. Ethics and Behavior, 2, 141 - 149. Galvin, S. L. & Herzog, H. A. (1992b). The ethical judgment of animal research. Ethics and Behavior, 2, 263 - 286. [Notice the use of “a” and “b” with the date. Without those letters “Galvin & Herzog (1992)” would be ambiguous. Also note that the order in the references list is alphabetical by title of the article] Herzog, H. A. (1998). Understanding animal activism. In L. Hart (Ed.), Responsible conduct of research in animal behavior (pp. 156 – 183). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Chapter in an edited book.] Herzog, H. (1999, November). Power, money, and gender: Status hierarchies and the animal protection movement in the United States. ISAZ Newsletter, 18, 2 - 5. Herzog, H. A., Jr., Betchart, N. S., &Pittman, R. B. (1991). Gender, sex role orientation, and attitudes toward animals. Anthrozoös, 4, 184 191. Herzog, H., Rowan, A., and Kossow, D. (2001). Social attitudes and animals. In D. J. Salem & A. N. Rowan (Eds.), The state of the animals (pp 55 - 69). Gaithersburg, MD: Humane Society Press. Miller, N. E. (1985). The value of behavioral research on animals. American Psychologist, 40, 423 - 440. National Academy of Sciences. (1991). Science, medicine, and animals. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Nickell, D., & Herzog, H. A., Jr. (1996). Ethical ideology and moral persuasion: Personal moral philosophy, gender, and judgments of proand anti-animal research propaganda. Society and Animals, 4, 53-64. Osburn, H. G. (2000). Coefficient alpha and related internal consistency reliability coefficients. Psychological Methods, 5, 343-355. Plous, S. (1991). An attitude survey of animal rights activists. Psychological Science, 2, 194-196. MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 18 Plous, S. (1996a). Attitudes toward the use of animals in psychological research and education: Results from a national survey of psychologists. American Psychologist, 51, 1167-1180. Plous, S. (1996b). Attitudes toward the use of animals in psychological research and education: Results from a national survey of psychology majors. Psychological Science, 7, 352-358. Schlenker, B. R., & Forsyth, D. R. (1977). On the ethics of psychological research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 369-396. Singh, B., & Forsyth, D. R. (1989). Sexual attitudes and moral values: The importance of idealism and relativism. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 27, 160-162. Tannenbaum, J., & Rowan, A. N. (1985, October). Rethinking the morality of animal research. The Hastings Center Report, 32-43. Ulrich, R. E. (1991). Animal rights, animal wrongs and the question of balance. Psychological Science, 2, 197-201. Wuensch, K. L., and Poteat, G. M. (1998). Evaluating the morality of animal research: Effects of ethical ideology, gender, and purpose. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 13, 139-150. When preparing a manuscript to be submitted for consideration for publication, APA wants you to double-space the reference list. I want you to single-space it, but with extra space between each citation and the next. I also want you to use hanging indentation. Here is how to do that: MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 19 MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 20 Appendix The Animal Rights and Misanthropy Scales Instructions Given to Respondents This questionnaire was designed to measure your attitudes about a number of potentially related things. You will find a series of statements below. Each represents a commonly held opinion and there are no right or wrong answers. You will probably disagree with some items and agree with others. We are interested in the extent to which you agree or disagree with such matters of opinion. Please read each statement carefully and then indicate the extent of your disagreement/agreement with each item according to the following scale: A B C D E strongly disagree disagree no opinion agree strongly agree The Animal Rights Scale Please indicate your response by filling in the appropriate circle (A, B, C, D, or E) on the multiple choice answer sheet. Please use a number 2 pencil. Mark only one response for each item. Please do not mark the questionnaire itself - save a tree by returning the questionnaire unmarked so we can use it again. Do not put any identifying information (such as name or social security number) on your answer sheet -- we want your responses to be confidential. 1. Humans have no right to displace wild animals by converting wilderness areas into farmlands, cities, and other things designed for people. 2. Animal research cannot be justified and should be stopped. 3. It is morally wrong to drink milk and eat eggs. 4. A human has no right to use a horse as a means of transportation (riding) or entertainment (racing). 5. It is wrong to wear leather jackets and pants. MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 21 6. Most medical research done on animals is unnecessary and invalid. 7. I have seriously considered becoming a vegetarian in an effort to save animal lives. 8. Pet owners are responsible for preventing their pets from killing other animals, such as cats killing mice or snakes eating live mice. 9. We need more regulations governing the use of animals in research. 10. It is morally wrong to eat beef and other "red" meat. 11. Insect pests (mosquitoes, cockroaches, flies, etc.) should be safely removed from the house rather than killed. 12. Animals should be granted the same rights as humans. 13. It is wrong to wear leather belts and shoes. 14. I would rather see humans die or suffer from disease than to see animals used in research. 15. Having extended basic rights to minorities and women, it is now time to extend them also to animals. 16. God put animals on Earth for man to use. 17. There are plenty of viable alternatives to the use of animals in biomedical and behavioral research. 18. Research on animals has little or no bearing on problems confronting people. 19. New surgical procedures and experimental drugs should be tested on animals before they are used on people. 20. I am very concerned about pain and suffering in animals. 21. Since many important questions cannot be answered by doing experiments on people, we are left with no alternatives but to do animal research. MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 22 22. It is a violation of an animal's rights to be held captive as a pet by a human. 23. It is wrong to wear animal fur (such as mink coats). 24. It is appropriate for humans to kill animals that destroy human property, for example, rats, mice, and pigeons. 25. Most cosmetics research done on animals is unnecessary and invalid. 26. It is morally wrong to eat chicken and fish. 27. Most psychological research done on animals is unnecessary and invalid. 28. Hunters play an important role in regulating the size of deer populations. Scoring Instructions. Numerically code the A,B,C,D,E response scale as 1,2,3,4,5 -- that is, the higher the number, the greater the agreement with the statement. Reflect (reverse score) items 16, 19, 21, 24, and 28. To obtain an overall score, simply compute, for each respondent, the average (mean) of the 28 items. Sample Statistics. For the currently reported sample, the mean was 2.38, the median was 2.36, the standard deviation was 0.54, and skewness was 0.38. The Misanthropy Scale 1. Humans are by nature basically corrupt. 2. Both history and current events show that human beings are basically wicked. 3. Planet earth would be better off if humans would just disappear from it. 4. Most people are basically good-natured. 5. I am proud to be a member of the human race. Scoring Instructions. Score this scale in the same way as the animal rights scale, reflecting items 4 and 5. MISANTHROPY, IDEALISM, & ANIMALS 23 Sample Statistics. For the current sample, the mean was 2.32, the median was 2.20, the standard deviation was 0.67, and skewness was 0.45. Sample Statistics for the Idealism Scale For the current sample, the mean was 3.65, the median was 3.70, the standard deviation was 0.53, and skewness was -0.06. Fifteen respondents had scores exactly equal to the median. Return to Wuensch’s Research Design Lessons