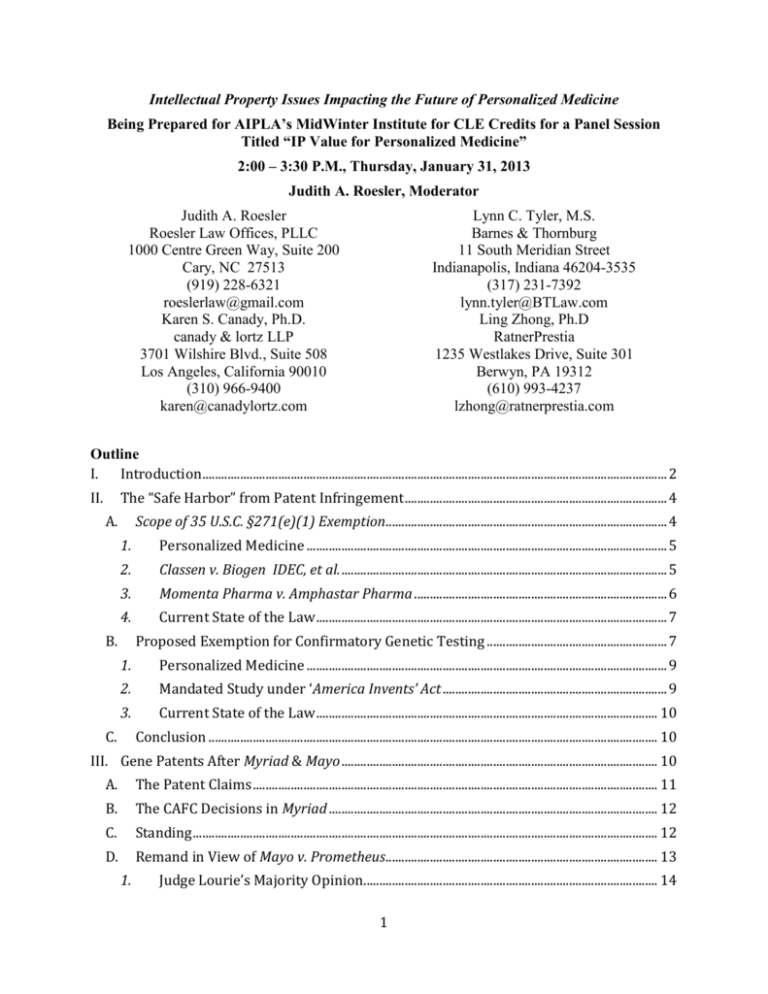

IP Value for Personalized Medicine - American Intellectual Property

advertisement