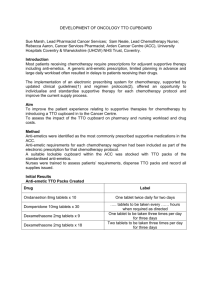

From the Economic Principles of my Cancer Treatment

advertisement

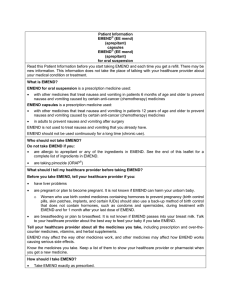

Excerpt from “The Economic Principles of my Cancer Treatment” by Joab Corey (under review for publication) Example 1: Inelasticity Perfectly inelastic demand is represented by a vertical demand curve and occurs with goods where the buyer will purchase the same quantity regardless of the price. Most students have trouble with elasticity in general, much less grasping the concept of purchasing a good regardless of the price, and they often ask if such a good really exists. The most common response by economists to this question is that life-saving medication is the best example of a good that reflects perfect inelasticity in that no matter the price, people will still want to buy the same amount. In reality this perfectly inelastic demand curve is more of a theoretical construction than a realistic description of behavior as their will be some price high enough to induce people to create or search for available substitutes. However, the idea that life-saving medication is very inelastic remains. My cancer treatment was filled with very expensive, but very necessary medications (including the chemotherapy itself) that I would have purchased regardless of the price. However, the most vivid example of this is when I went to purchase some necessary medications before my first chemotherapy treatment. One of the prescriptions was for the pill Emend which consists of three pills, one taken each day the first three days of a chemotherapy cycle. The purpose of this pill is to help prevent nausea and is so necessary that the hospital will provide it for you (and charge you for it) before they start your chemotherapy cycle if you don’t purchase it on your own. One Emend pack, which consists of three pills, costs about $330 as of this writing. While waiting for my prescriptions to be filled the pharmacist and I engaged in the following dialogue: Pharmacist: This prescription for Emend costs $330. Do you still want it?1 Myself: Do I still need it? Pharmacist: Well, yes. Myself: Then I guess I still want it. The basic point of this dialogue is that she could have said that the pills cost 1,000 dollars, or even 5,000 dollars, and I still would have wanted them. This story drives home the point of inelasticity as whether the price for the Emend prescription was $1 or $5,000, I still would have purchased the same amount.2 The same is true for the chemotherapy itself. Even a considerable change in the price of chemotherapy would not have changed my demand for the treatment. If the price rose substantially then I would have still wanted the prescribed number of cycles and if the price dropped substantially (even as low as one cent per cycle) then I would have not wanted any more chemotherapy above the prescribed dosage for reasons obvious to anyone who has received chemotherapy treatments before3. This idea can be applied to any number of medications used for a variety of medical afflictions. Even a professor who suffers from severe 1 In retrospect, I think the pharmacist was trying to find a polite way of asking if I could still pay for the expensive medication rather than if I really wanted it. However, this thought did not enter my head at the time 2 Despite the necessity of the Emend pills, I still never got over the thought that I was swallowing over $100 with every one of those pills. 3 The side effects of chemotherapy are very unpleasant. They often include but are not limited to nausea, hair loss, fatigue, dizziness, ringing of the ears, headaches, mouth sores, blood clots, and low blood cell count levels that result in a higher risk of other disease and infections. It also includes other long-term negative effects such as increased risk of other cancers and sterility. migraines can use inelasticity when discussing how much he or she would pay to be free of their headaches. An economics professor in the hospital or in a pharmacy is the perfect storm for memorable classroom inelasticity examples.