10 When life-prolonging treatment is withdrawn

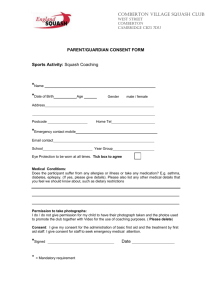

advertisement