BUS-606-Week-3-DQ-1-Thinking-Styles

advertisement

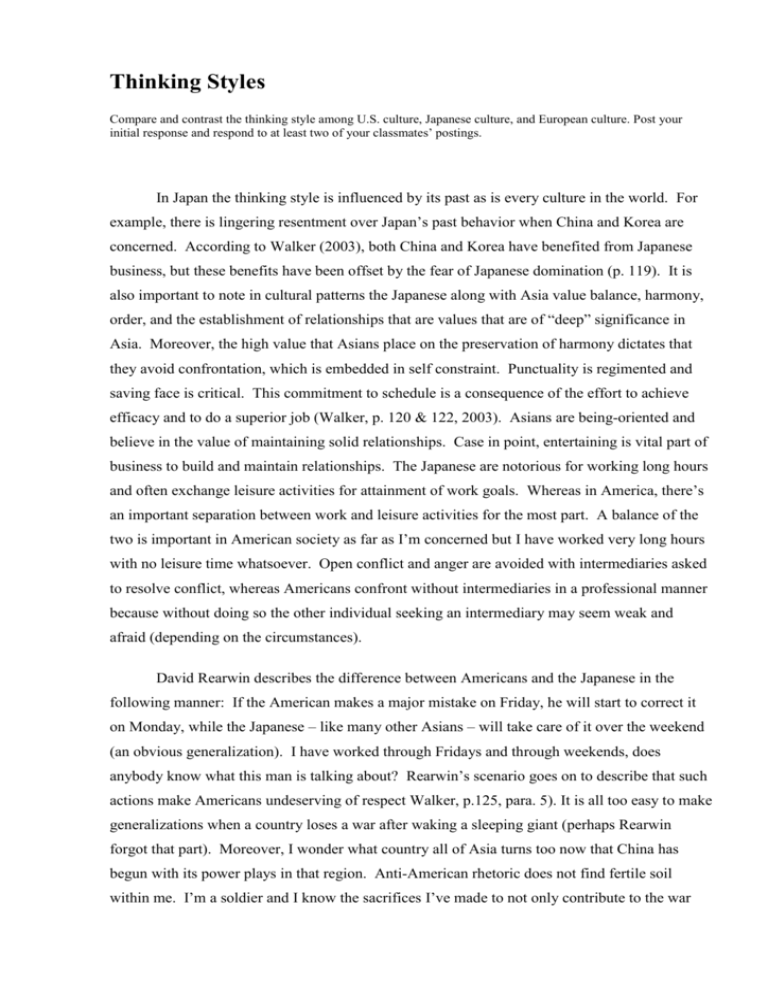

Thinking Styles Compare and contrast the thinking style among U.S. culture, Japanese culture, and European culture. Post your initial response and respond to at least two of your classmates’ postings. In Japan the thinking style is influenced by its past as is every culture in the world. For example, there is lingering resentment over Japan’s past behavior when China and Korea are concerned. According to Walker (2003), both China and Korea have benefited from Japanese business, but these benefits have been offset by the fear of Japanese domination (p. 119). It is also important to note in cultural patterns the Japanese along with Asia value balance, harmony, order, and the establishment of relationships that are values that are of “deep” significance in Asia. Moreover, the high value that Asians place on the preservation of harmony dictates that they avoid confrontation, which is embedded in self constraint. Punctuality is regimented and saving face is critical. This commitment to schedule is a consequence of the effort to achieve efficacy and to do a superior job (Walker, p. 120 & 122, 2003). Asians are being-oriented and believe in the value of maintaining solid relationships. Case in point, entertaining is vital part of business to build and maintain relationships. The Japanese are notorious for working long hours and often exchange leisure activities for attainment of work goals. Whereas in America, there’s an important separation between work and leisure activities for the most part. A balance of the two is important in American society as far as I’m concerned but I have worked very long hours with no leisure time whatsoever. Open conflict and anger are avoided with intermediaries asked to resolve conflict, whereas Americans confront without intermediaries in a professional manner because without doing so the other individual seeking an intermediary may seem weak and afraid (depending on the circumstances). David Rearwin describes the difference between Americans and the Japanese in the following manner: If the American makes a major mistake on Friday, he will start to correct it on Monday, while the Japanese – like many other Asians – will take care of it over the weekend (an obvious generalization). I have worked through Fridays and through weekends, does anybody know what this man is talking about? Rearwin’s scenario goes on to describe that such actions make Americans undeserving of respect Walker, p.125, para. 5). It is all too easy to make generalizations when a country loses a war after waking a sleeping giant (perhaps Rearwin forgot that part). Moreover, I wonder what country all of Asia turns too now that China has begun with its power plays in that region. Anti-American rhetoric does not find fertile soil within me. I’m a soldier and I know the sacrifices I’ve made to not only contribute to the war effort but to also support the balance in the world. I wonder how easily China would swallow up Japan if American forces were not present. I digress, my apologies. In America problems are seen as a challenge and as an opportunity to try something new. In the U.S.-American mindset, there is no problem without a solution. Consequently, U.S.-American business professionals are often perceived as assertive, ambitious, and eager to take initiative. Any interruptions or deviations to project plans and agendas are usually unwelcomed. Further, at meetings, for example individuals who stray from business at hand or who interrupt while others are speaking are considered rude (Walker, p. 165 & 166, 2003). American business professionals tend to separate business matters from interpersonal relationships. Allowing personal likes and dislikes to affect a business deal, or spending time at work attending to personal affairs is seemed as inappropriate. U.S. Americans see time as rigid, precise concept, a commodity to be saved and spent wisely, not wasted or lost (Walker, p. 167, 2003). Unlike the Japanese a tardiness of five minutes or so is seemed as acceptable according to Walker. However, I personally do not see it as appropriate unless there are uncontrollable factors involved. The American comes from a doing-oriented culture and aside from the occasional social event I believe we are mostly about business. We are focused on results that are measurable by objective standards and emphasize the accomplishment of tasks over relationship building (Walker, p. 183, 2003). We prefer explicit and detailed information over ambiguous or brief messages. Americans prefer direct communication and feedback should be confined to professional matters and we also view open discussion and resolution of conflict as signs of honesty and trust. Displays of emotion and emotional appeals in a business setting are generally considered unprofessional (Walker, p. 173, 2003). Western Europe is highly dynamic region that has switched to a single European currency, the Euro, and this is a milestone in the integration of key European countries. This will lead to a greater unification of political systems. Western Europeans share the urge to achieve control and orientations that are manifested in the use of slow, methodical decisionmaking processes that are able to adjust to circumstances (Walker, p. 124 & 125, 2003). To the Europeans there’s a linear, structured approach that signifies efficiency and quality. Case in point, whatever business task is at hand supersedes any other demands. Punctuality is highly valued, however, this does not apply to all countries such as Green, Spain, Italy, and Portugal where arriving a few minutes late is acceptable. The guiding rule, which fits with the past orientation towards time, is that what was successful in the past will continue to be successful. In contrast, Scandinavian countries demonstrate the future orientation more clearly. The being orientation of Western European countries is reflected in their emphasis of quality of life (Belgium, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Malta, Monaco, Portugal and Spain). Doing-oriented cultures such as the Dutch are impressed by someone’s achievement, ability to take risks, drive, and charisma rather than that person’s social and hierarchical status (Walker, p. 141 & 142, 2003). There’s a mix of low and high-context cultures. The low-context communicators can be seen by the high-context communicators as abrupt, cold and even indifferent. The same mix is seen in direct and indirect orientations. Germany, Switzerland, Austria, the Netherlands and the Scandinavian countries tend to meet conflict head on, whereas the rest of European countries are have an indirect communication style. Although corporate cultures differ from country to country, there’s a strong hierarchical orientation towards authority (Walker, p. 147, 2003). Most Western European cultures highly value individualism. There are both universalistic and particularistic orientations. In competitiveness, Western Europe is different from Americans because their competitiveness is a function of a widely held desire to improve products. Security and risk aversion are important considerations for individuals in order-oriented cultures for Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Greece, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and France. The other remaining countries have some tendencies towards flexibility (Walker, p. 150 & 151). Both the deductive and inductive orientation toward thinking is exhibited. Linear systemic reasoning take place in Germany, United Kingdom and Scandinavia. Reference Walker, D., Walker, T., & Schmits, J. (2003). Doing business internationally: The guide to cross-cultural success (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. ISBN: 9780071378321 (or custom ISBN: 9781121558199)