Family Law Practitioner`s Association of Queensland

advertisement

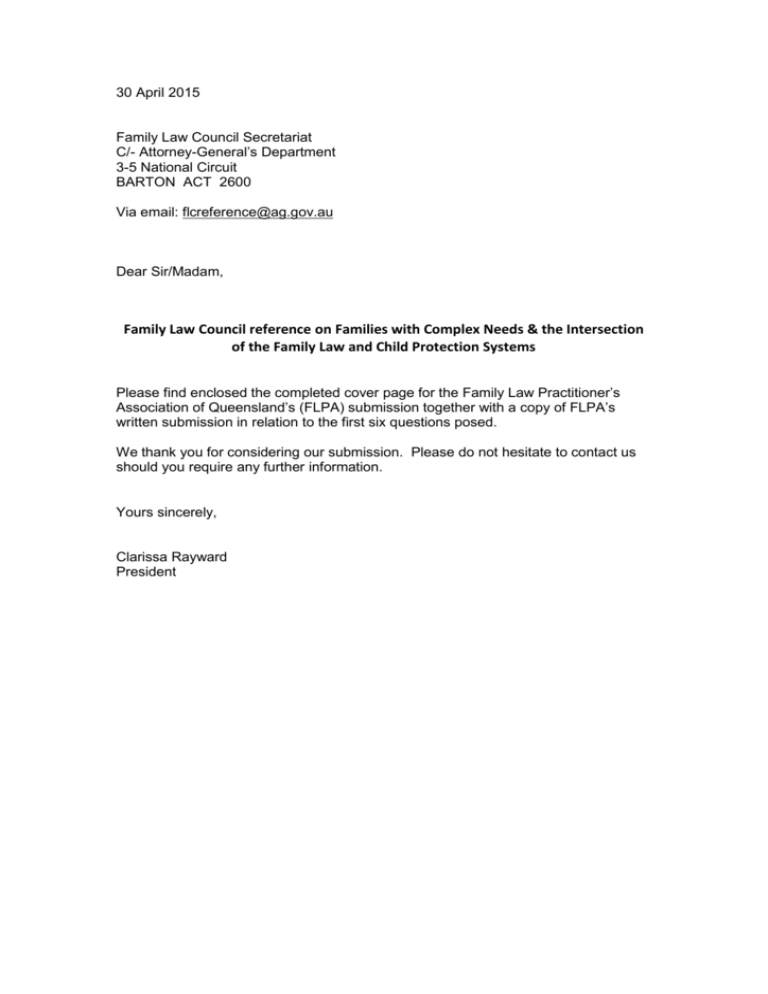

30 April 2015 Family Law Council Secretariat C/- Attorney-General’s Department 3-5 National Circuit BARTON ACT 2600 Via email: flcreference@ag.gov.au Dear Sir/Madam, Family Law Council reference on Families with Complex Needs & the Intersection of the Family Law and Child Protection Systems Please find enclosed the completed cover page for the Family Law Practitioner’s Association of Queensland’s (FLPA) submission together with a copy of FLPA’s written submission in relation to the first six questions posed. We thank you for considering our submission. Please do not hesitate to contact us should you require any further information. Yours sincerely, Clarissa Rayward President 1. What are the experiences of children and families who are involved in both child protection and family law proceedings? How might these experiences be improved? Children and families who are involved in both child protection and family law proceedings often experience confusion for a number of reasons including: 1. Some Magistrates Courts across the country will exercise jurisdiction under the Family Law Act, for example in northern New South Wales, but a number of other Magistrates Courts in Queensland, for example, will not. As a result, hearings in each of these proceedings usually occur in different buildings. 2. There are significant differences in the law to be applied by each Court, in each Court’s processes and even in the participants in the proceedings (particularly if they identify as being Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander). 3. In circumstances where the Department has acted to remove one child, but not other children born subsequently, this can lead families to experience confusion and concern regarding the legal system and processes. Whilst it is understood that the Department must consider the risk of harm to each child, there appears to have been some inconsistency at times in the past in terms of removal of children such that grandparents, aunts and uncles and even siblings have been told by the Department to file family law proceedings due to the Department’s reluctance/failure to act despite them having removed other siblings. 4. The level of support offered by the Department when involved in the child protection system is often different to that provided when involved in family law proceedings. An example of this is when support is provided to kinship carers of children, the subject of child protection orders, to facilitate time for children with their parents, whereas no similar support is available in family law proceedings. There are also differences in financial, medical and educational support for the children provided. FLPA members have experienced challenges in trying to arrange time between siblings when one child has been the subject of a Child Protection Order and another, the subject of family law proceedings. They have also experienced issues trying to work with the Department to facilitate time between two children (one of whom was the subject of a child protection order and the other the subject of a Family Law Act order) and their mother who was at that time incarcerated. In that case, despite both children being placed with the same kinship carer, the Department would not help facilitate time for the mother in prison with the child who was not the subject of a child protection order even though they were assisting with transport for the other child. That same carer also experienced differences in the level of financial, medical and educational support provided for each child as each was being dealt with by a different system concurrently. She was eligible for a lot more support for the child, the subject of the child protection order. Children who are the subject of family law proceedings and whose siblings may be the subject of child protection proceedings often struggle to understand why there are different arrangements in place for their siblings and why they can’t be together with their siblings. Dependent on their ages, children may also experience a different 2 level of involvement in the decision making (eg family group meetings in the child protection context) and the Court processes, depending on the jurisdiction. Children and families are also often worn down by having to tell their story to so many different people when involved in different proceedings. For example their lawyers so they can prepare their affidavits, to the Department, to a family report writer, to a social assessment report writer and/or to a psychiatrist. Children and families’ experiences could be improved by: 1. Courts being properly resourced to hear and determine ‘hybrid’ cases so that all issues in relation to a sibship can be dealt with at the one time. This may involve a transfer of proceedings such that the one Court could determine all relevant issues. This would also require additional funding to both Court systems to ensure that cases involving both child protection issues and family law issues could be heard and determined in a timely manner, in addition to their core caseloads. 2. Ensuring that, in appropriate and practical circumstances, Departmental practice is to assist with the facilitation of time with all children in the sibship not just those the subject of child protection orders. 3. A change to Departmental practice in cases where they have a current child protection order for a child, not encouraging others to commence proceedings in relation to that child’s siblings, to avoid their child protection responsibilities. 4. In the event family law proceedings are on foot, and in cases where the Department has previously been involved with the family, the Department seeking to intervene in family law proceedings to ensure that the Court determining the family law issues has access to all relevant information before it. 5. If proceedings are to remain between the two Courts, information/evidence should be shared between the Courts without the parties having to seek specific leave. The Rules of each Court should be amended to facilitate this. 6. Where possible the same experts should be engaged to ensure that parties/the children are not exposed to too many experts. (It is noted in that regard that those experts will need to consider different issues dependent on the nature of the current proceedings.) 2) What problems do practitioners and services face in supporting clients who are involved in both child protection and family law proceedings? How might these problems be addressed? One of the biggest problems facing practitioners in supporting clients who are involved in both types of proceedings is trying to assist them to understand the differences in the systems. As outlined above, not only do the Courts operate differently; cases are conducted differently; parties/children’s level of participation will be different; the terminology used is different; the grants of Legal Aid are significantly different and more importantly, the law/legal tests to be applied are vastly different. Child protection proceedings are conducted in local Magistrates Courts and are often in different locations to the family law proceedings. Clients have been known to turn 3 up at the wrong Court on the wrong day as a result. As detailed above, it would be of assistance if the one, properly resourced Court, could deal with all child related matters. It is challenging for practitioners and services to assist clients in understanding why they may be eligible for some services/assistance in relation to some of the children in their care but not others. For example, those children within the Child Protection system may be eligible for certain medical treatment, access to education plans, assistance and support in facilitating time with parents and the like whereas these services may not be available in family law proceedings. Some consistency to the provision of services for children who are part of a sibship would be ideal. Practitioners also face the challenge of evidence gathering when involved in different proceedings. Clients are also often worn down by having to tell their story to so many different people and often think that they have told their lawyer something but have not. Relevant matters may then be left out of affidavit material placed before the Court because the client thinks it is already there. Also, some evidence may be available in the family law proceedings which may be of assistance to the Court in the child protection proceedings and the reverse. However, to obtain that information, leave would need to be granted or the other Court would have to make a request for the other Court’s file. Once the information is available there are some evidentiary challenges in placing that material before the Court and in particular as to who is to be responsible for arranging (and paying for) the author of such material to give evidence etc. This could be addressed by a protocol about the exchange of information between the Courts or a Court Rule to the effect that leave does not need to be obtained for a party to rely upon evidence from one Court in the other. Further, on occasions, one Court may make findings about particular issues which may be of relevance in the other proceedings. Clients are often legally aided or selfrepresented in child protection proceedings and may not have access to transcripts of proceedings before the other Court. It would be of assistance if orders could be made for the preparation of transcripts which could be placed on Court files so that the parties/the other Court could make reference to it if required. Another significant issue, is that of supervised time. Children involved in child protection proceedings are often able to spend more regular time with their parents than can be facilitated in a family law context due to the lack of availability of services and the cost of the provision of supervised time. Also, issues have arisen in the past where interpreters have been required so that the supervisor can understand what is being said to the children. Funding was available for this through the Department for children the subject of child protection proceedings but not in a family law context. Again, consistency in approach would be preferred. Further, funding for interpreters for supervised time should be made available irrespective of the type of proceedings the parties are engaged in. 3) What are the possible benefits for families of enabling Children’s Courts to make parenting orders under Part VII of the Family Law Act? In what circumstances would this power be useful? What would be the likely challenges for practice that might be created by this change? Possible benefits for families identified by FLPA members are listed below: 4 1. the ability for separated families to have their dispute resolved in a single Court proceeding dealing with both child protection matters and family law matters, circumventing any need for proceedings to be litigated in two 2. a more straight forward and streamlined process for separated families, once proceedings are commenced in the Children’s Court. 3. a reduction in costs for parties in having to, in effect, start again by commencing family law proceedings if a child protection order is not made. If the Children’s Court were enabled to make parenting orders under Part VII of the Family Law Act, the power would be useful in circumstances where: 1. the Department determines to withdraw a Children’s Court application because a viable carer is identified and that carer has applied for, or has indicated a willingness to apply to the Family Court for parenting orders; 2. where one or more of the parties to the proceedings in the Children’s Court is assessed by the Court as being in a position to adequately protect the child or children from harm. Ultimately, if the Children’s Court had the requisite power, orders could be made without the need for further proceedings to be brought in the Family Court. This would prevent outcomes where orders protecting the child or children (in line with the Department’s intention) are not ultimately made, whether by reason of a failure on the part of the viable carer to bring an application in the Family Court at all, or due to the fact that the outcome in the Family Court jurisdiction is contrary to what the Department had intended. The challenges for practice which might be created by such a change include: 1. a reluctance on the part of the Department or Judicial Officers in the Children’s Court to have further involvement in the matter once the child protection issues are determined; 2. resourcing issues for the Children’s Court to allow for Judicial Officer training and education in relation to family law legislation and rules, and an increase in workload through lengthened (or additional) hearings and supplementary material being filed relevant to family law issues; and 3. whether such proceedings are to be conducted in a closed Court or open Court. 4) What are the possible benefits for families of enabling the Family Court to make Children’s Court orders? In what circumstances would this power be useful? What challenges for practice might be created by this change? A number of the possible benefits for families identified by FLPA members are listed below: 1. a greater awareness being required amongst lawyers practising in family law of the intricacies of child protection laws, and in turn a greater pool of lawyers able and willing to receive instructions and provide advice in child protection 5 matters; 2. the preparation of affidavit evidence and collation of relevant information by the Department for the assistance of the Court when involved as a party to the proceedings in a more concise and focused manner (in the alternative to the usual production of an often lengthy file through the subpoena process); 3. the ability for separated families to have their dispute resolved in a single Court proceeding dealing with both family law and child protection matters, circumventing any need for proceedings to be litigated in two separate Courts; 4. a more straight forward and streamlined process for separated families, once proceedings are commenced in the Family Court if there are welfare issues involved; 5. easier access and greater involvement of third parties (extended family members or friends) seeking to be considered as a viable alternative if the child cannot remain safely in the care of either parent, in family law proceedings which involve separated parents and the Department; Enabling Family Courts to make Children’s Court orders would be useful particularly in circumstances where none of the parties to the proceedings in the Family Court are considered to be in a position to adequately protect the child or children from harm. The unenviable position in which Judicial Officers can be placed under existing laws was highlighted in the case of Ray and Anor & Males and Ors [2009] FamCA 219 by Justice Benjamin, and later in the appeal of that matter by the Full Court in Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services & Ray and Ors [2010] FamCAFC 258. His Honour Justice Benjamin in a later case of Fargo & Lark [2011] FamCA 238 at [14] referred to his obligation in relation to determining what orders needed to be put in place for the child subject to those proceedings as follows: “I will be looking at the least worst option. There is no safe option. The inevitable consequence is that no matter what outcome I provide, the child will be harmed.” In relation to the involvement of the Department, Justice Benjamin at [16] and [17] observed that: “At present, all that can be done is invite State Welfare participation [under section 91B of the Act], however, such invitation is generally not taken up… The consequence is that the artificial division of the private parenting law in the Federal sphere and the child welfare law in the State and Territory sphere leaves children at risk, which could otherwise be avoided or reduced. The ability to impose duties of care or at least supervision on the State welfare bodies is not available except if such bodies volunteer themselves to that course.” His Honour went on at [18] to: “urge the Federal and State Attorneys General and Justice Ministers to jointly 6 introduce policy and legislation to remedy this problem and provide the legislative and resource structures to protect and nurture the children who are most at risk. I am aware that there are serious Constitutional difficulties, however, these can be overcome by referral of powers through constructive, co-operative and effective State and Federal policy.” FLPA submits that serious consideration must be given to ways in which this problem can be overcome. The challenges for practice which might be created by such a change include: 1. resourcing issues for the Department resulting from staff training and education in relation to family law legislation and rules, and the need for representatives to appear at Court events and participate in proceedings generally; and 2. resourcing issues for the Family Court to allow for Judicial Officer training and education in relation to child protection legislation and rules, and lengthened hearings through the involvement of an additional party; and 3. whether such proceedings are to be conducted in a closed Court or open Court; and 4. whether the integration of child protection jurisdiction in the Family Court system would have an adverse impact on the delivery of services to families with no child protection issues at large given that child protection issues are often, by necessity, dealt with quite urgently in the State system. That style of listing would have a direct impact on the processing of other cases in a Court which is already struggling with resourcing issues. As a result, if this was to be implemented additional resources would be required in the Family Court system for the Court to be able to keep to its existing listing/determination guidelines. 5) Are there any legislative or practice changes that would help to minimise the duplication of reports involved when families move between the Family Court and Children’s Court? This question presumes that the Family Court will not have jurisdiction to make Children’s Court orders (and that separate Children’s Court proceedings will be on foot). While, ideally, the representatives (in Family Court proceedings) would be stakeholders in any Departmental intervention and communication (in Children’s Court proceedings), and reports could be commissioned from a single expert for use in both sets of proceedings, the challenge is that:1. The focus of reporting in the Family Court and the Children’s Court is often on different issues (in the Family Court, focus is often on the competing proposals of the litigants, with recommendations often made against that background, taking account of factors raised by each litigant, but in Children’s Court, report writers usually consider harm or a risk of harm and their recommendations are usually directed to analysis of a particular outcome, contended for by the Department, and based on a sub-stratum of facts distilled by the Department). The difference is subtle but important, as it 7 means that expert opinions are buttressed in different ways; 2. Reports prepared for child protection matters often involve interviews with people who may not be witnesses in the family law proceedings and who may have access to information which is not in evidence before the Family Court; 3. It is unlikely that the Children’s Court proceedings would run concurrently with the Family Court proceedings, and timing differences would mean that any ‘point in time’ report commissioned by an expert in one of the proceedings would require updating and/or focus on particular issues which were not addressed in the initial report in order to be of use in the other proceedings. The concern is, therefore, that updating reports to account for these factors would, in any event, consume the same resources as duplication of reports. Further, concern is raised that use of a single expert for reporting in each of the separate proceedings may give rise to dissymmetry in instructions given to the expert, and the way in which those instructions are provided (particularly where it is not necessarily the case that the same legal representatives will be involved in the separate Family Court and Children’s Court proceedings), giving rise to possible challenge to the expert’s opinion in one (or both) of the proceedings (e.g. on the basis that any opinion set forth in an updated report in one of the proceedings is flawed as a result of the instructions provided in the other proceedings), and applications for the appointments of further single experts and/or adversarial experts in one (or both) of those proceedings. Again, therefore, attempt at avoiding duplication, in practice, gives rise to further scope for duplication. It is therefore the submission of FLPA that the duplication of reporting is an unavoidable reality of two separate Court processes, and that the better course is to facilitate information sharing as between the Department and the Family Court, so that the report writing process is more fulsome (as a result of all information being able to be put before the experts in each of the separate proceedings) and less timeconsuming (as a result of information not being required to be produced by the Department pursuant to formal legal process). How this sharing of information might occur is set forth in FLPA’s response to Question 2 and 6 below. 6) How could the sharing of information and collaborative agencies be improved? If there is no jurisdiction granted to the Family Court to make child protection orders It is presumed, for the purpose of this question, that it is directed to the situation where there is child protection agency (‘Department’) involvement, but where the Department has not commenced any proceedings (or that any Children’s Court proceedings have been concluded). Where families are accessing both the Family Court, and simultaneously engaging with the Department, there will usually be a factor which means that an Independent Children’s Lawyer (“ICL”) has been, or should be, appointed, in the Family Court proceedings. It is central to the task of the Judicial Officer in the Family Court proceedings that information arising as a result of Departmental involvement is before it. Equally, it is central to the task of the Department that it be possessed of information to permit its officers to undertake all investigations and interventions deemed necessary. Sharing of information aids in the achievement of both 8 tasks. Whilst there are provisions of the Family Law Act and a Protocol with the Queensland Department for information sharing in place, it is submitted that there are still currently some challenges in ensuring that this sharing of information occurs. The broad experience of those FLPA members who have had input into these submissions is that the Department takes a narrow interpretation of the scope of its involvement. That involvement is usually managed by a non-lawyer case worker, with limited to no knowledge of Part VII of the Family Law Act, and no experience in Family Court proceedings. That case worker is usually focused primarily on the Departmental agenda, and in practical terms, disregards the fact of the progressing Family Court proceedings when meeting that agenda. This, it is submitted, is a missed opportunity for families. The factors at large in the Departmental involvement will inevitably be, at least in part, the same factors at large in the Family Court proceedings. For a Judicial Officer in the Family Court proceedings to:1. Have knowledge of the Department’s objectives and proposed process when making orders; and 2. Know that the Department is aware of orders made in those proceedings, and that those orders are being taken into account in the Department’s approach to its engagement with a particular family; can, it is submitted, only be positive in achieving outcomes for families accessing the Family Court system. This synergy between the Family Court and Department in the making of, and implementation of, orders can be achieved, it is submitted by FLPA, by the Department inviting stakeholders in the Family Court proceedings (including an ICL where appointed) to be involved in the Departmental process (e.g. family meetings, case meetings, etc). Further, requiring the Department to intervene in a meaningful way in family law proceedings where the Department is actively engaged with participants in those proceedings would assist greatly. For example, the Department should be required to file an affidavit in the family law proceedings as to the objectives and expectations of the Department relevant to a party to those proceedings and annexing any case plans. The Court could provide to the Department, at the conclusion of the proceedings, a copy of the Orders ultimately made by the Judicial Officer and any Reasons for Judgment delivered together with any reports prepared in the course of the proceedings. The process can further be enhanced by, where a particular Separate Representative has been appointed in previously concluded Children’s Court proceedings, that same representative being appointed as ICL in the Family Court proceedings or the reverse. Meanwhile:1. Sharing of information between the Family Court and the Department can be achieved by Judicial Officers making a procedural order when an ICL is appointed in terms that the ICL is authorised to provide to the Department such information as is necessary to inform the Department as to the issues raised in and the status of the Family Court proceedings (e.g. Applications of 9 the parties, Orders and Directions made, and upcoming Court events) and to, unless the ICL considers it inappropriate to do so, provide any reports prepared in the Family Court proceedings to the Department; 2. A Form targeted to specific questions (in the style of, for example, a Notice of Risk) can be developed for completion by a Departmental lawyer upon request by a Judicial Officer or an ICL, so that the preliminary information as to Departmental involvement (requested under Section 69ZW of the Act) is more fulsome (the present concern is that requests made of the Department are met with no response, or that insufficient information to be of use in the Family Court proceedings is provided in response); 3. Streamlining of the provision of information and documents specifically requested of the Department can be achieved by the introduction of a procedural form (similar to a Third Party Disclosure Notice) to allow parties and/or ICLs to procure from the Department specific documents and reports from the Department file (rather than the entire file, which is often voluminous, and which usually contains many duplicated documents), rather than via Subpoena or other formal process. 4. A protocol about the exchange of information between the Courts or a Court Rule to the effect that leave does not need to be obtained for a party to rely upon evidence from one Court in the other would assist. 5. The provision of transcripts from the different Court proceedings may also assist in limiting the issues to be determined in either Court. It is submitted that there cannot be sharing of such information with family violence services, or drug and alcohol agencies, given the inability to bind those organisations to any protocols as to the maintenance of privacy of Reports procured during the Family Court process, and appropriate treatment of information contained within them. If jurisdiction is granted to the Family Court to make child protection orders In this situation, the Department would be a party to the Family Court proceedings, and would therefore have the same rights, and entitlements, as parties, in terms of filing of evidence in support of the outcomes sought by it, and disclosure of the evidence on which other litigants rely. In this situation, it is submitted that it is essential that the conduct of the matter be allocated to a Departmental lawyer (rather than an advocate at State Law level), as availability for engagement in the matter (both with the parties, and any ICL) allows outcomes to be achieved (procedurally and globally) other than at Court events. 10