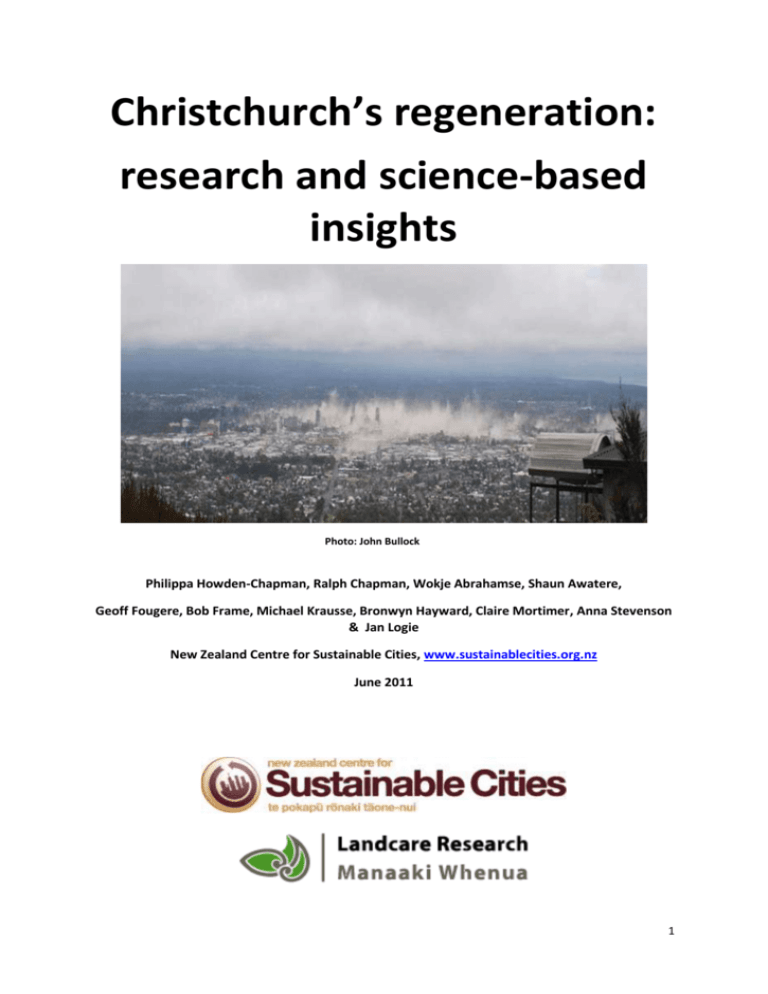

Christchurch*s regeneration: - New Zealand Centre for Sustainable

advertisement