Reading Further - Saving the Ganges

advertisement

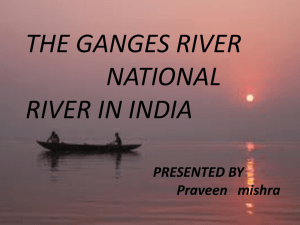

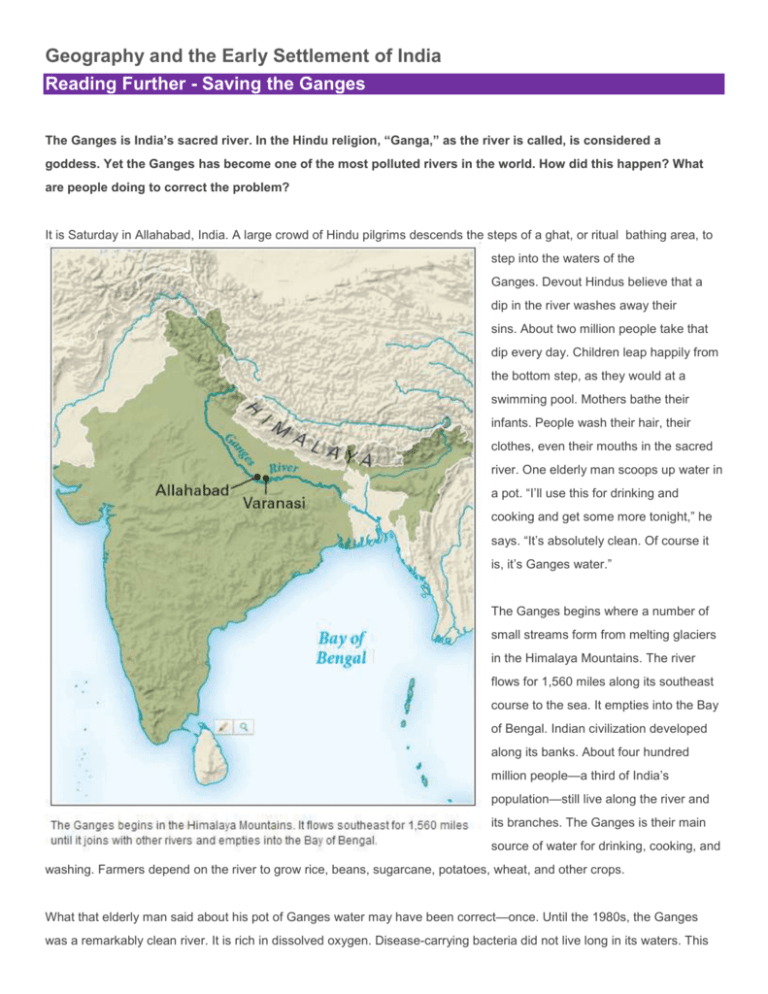

Geography and the Early Settlement of India Reading Further - Saving the Ganges The Ganges is India’s sacred river. In the Hindu religion, “Ganga,” as the river is called, is considered a goddess. Yet the Ganges has become one of the most polluted rivers in the world. How did this happen? What are people doing to correct the problem? It is Saturday in Allahabad, India. A large crowd of Hindu pilgrims descends the steps of a ghat, or ritual bathing area, to step into the waters of the Ganges. Devout Hindus believe that a dip in the river washes away their sins. About two million people take that dip every day. Children leap happily from the bottom step, as they would at a swimming pool. Mothers bathe their infants. People wash their hair, their clothes, even their mouths in the sacred river. One elderly man scoops up water in a pot. “I’ll use this for drinking and cooking and get some more tonight,” he says. “It’s absolutely clean. Of course it is, it’s Ganges water.” The Ganges begins where a number of small streams form from melting glaciers in the Himalaya Mountains. The river flows for 1,560 miles along its southeast course to the sea. It empties into the Bay of Bengal. Indian civilization developed along its banks. About four hundred million people—a third of India’s population—still live along the river and its branches. The Ganges is their main source of water for drinking, cooking, and washing. Farmers depend on the river to grow rice, beans, sugarcane, potatoes, wheat, and other crops. What that elderly man said about his pot of Ganges water may have been correct—once. Until the 1980s, the Ganges was a remarkably clean river. It is rich in dissolved oxygen. Disease-carrying bacteria did not live long in its waters. This was largely due to bacteria-eating viruses called bacteriophages. Unlike most river water, a pot of Ganges water would stay fresh for a long time. The river’s self-purifying nature may be one reason why the Hindu people considered the Ganges a goddess. Today, however, the situation is very different. The Ganges has become so polluted that it can no longer clean itself. Its waters are now unhealthful not only for drinking and bathing but for farming as well. Ancient River, Modern Problems The main source of pollution is untreated sewage. The Ganges flows past some of India’s largest cities. In the last 60 years, India has struggled to develop a modern economy. While population and industry have grown enormously, sanitation has not kept pace. Fewer than half of India’s people have modern plumbing. Millions of gallons of sewage from more than 100 cities pour into the Ganges each day. Treatment plants can handle only a fraction of it. Much sewage does not reach the plants because many sewers are broken. Electricity sometimes goes out. Then the plants shut down, but the sewage keeps flowing. And many cities along the Ganges have no sewage treatment plants at all. Sewage is not the only problem. Cows swim in the Ganges. People wash their laundry in it. Dead bodies and body parts drift in the water, because traditional Hindus do not bury their dead. They cremate, or burn, the bodies. Many Hindus ask to be cremated on the Ganges’ banks. Their ashes are put in the river. But some bodies do not burn completely. And some people are too poor to buy firewood. They simply put the dead bodies of their loved ones into the river. The pollution is very bad at Varanasi. This is a city downstream from Allahabad. To Hindus, Varanasi is the holiest of cities. Every year, millions of pilgrims bathe at its more than 75 ghats. As it enters Varanasi, the Ganges contains 120 times more disease-causing bacteria than is safe for bathing. Then it flows past 24 sewers. Four miles downstream, the bacterial count is3,000 times the safe level. Each day, more than 1,000 Indian children die of cholera, typhoid, or hepatitis. These are diseases caused by water-borne bacteria. There are also the factories and farms. Leather tanning, cloth making, and fertilizer manufacturing use cancer-causing chemicals that end up in the Ganges. And when farmers spray their crops to kill insect pests, these poisons flow into the Ganges, too. The life-giving Ganga has become an agent of death. A Hero of the Planet Dr. Veer Bhadra Mishra is a Hindu priest. He is the head of Sankat Mochan, Varanasi’s second-largest temple. Every morning, he takes his ritual dip in the Ganges. But more than most Hindus, he knows better than to drink the water. Mishra is a scientist, a water engineer who was once a university professor. He has made it his life’s work to clean up “Mother Ganga.” “All our rivers have stories,” Mishra says. “All our rivers are important. But there is nothing anywhere like the Ganga.” Mishra was born a priest. The leadership of his temple has passed from father to eldest son since the 16th century. He inherited the job when he was 14. But his mother urged him to attend college, too. No one in his family had ever been to school. Mishra believes it happened because the Ganges needed his help. Mishra’s education led him to understand that the Ganges was in trouble. But it seemed to him that nobody in India’s government was interested in doing anything about the dangerous pollution. Even other Hindu priests seemed not to care about the problem. So, in 1982, Mishra started the Sankat Mochan Foundation to help people living along the Ganges. The foundation set up a program called “Campaign for a Clean Ganga.” Its goal is to educate people about the causes of pollution. It maintains a Web site, posting articles about environmental issues. India’s news media may use the information for free. Donations came from the United States and other nations. Other foundations, governments, and people also contributed. In 1999, Dr. Mishra won a Time magazine “Hero of the Planet” award. Three years later, the United Nations honored him. The Indian government began to pay attention, too. In 1986, it launched the Ganga Action Plan, or GAP. The plan was to use sewage treatment plants to clean up the Ganges. The GAP was an expensive failure. There were not enough plants to handle the amount of sewage. There was not enough power to run the plants. By 2002, the Ganges was more polluted than ever. Dr. Mishra did not give up. He had another plan that would use simpler technology. With a group of California scientists, he developed a system that did not need electricity. It used gravity to divert pollutants from the Ganges into ponds where they would be stored for 45 days. Helpful bacteria, algae, and sunlight would break the pollutants down into harmless substances. Mishra wanted to try out this plan in Varanasi. He believed it would be cheaper and more effective than the government’s plan. The Varanasi city council accepted the idea. But the state and national governments turned it down. Mishra knew that it would take time to gain acceptance for his plan. In the meantime, he began to educate the people of his city. He wanted to change their age-old habits that harmed the river. His foundation met with priests and pilgrims. It organized citizens and children. Young workers cleaned up litter from the banks of the Ganges. But the problem was so huge that these efforts had little effect. Scientists from other countries heard about Mishra’s project. Steve Hamner, a scientist from Montana State University, traveled to India in 2003. He met with Dr. Mishra and other Indian scientists. Hamner and an Indian government lab made detailed studies of Ganges water. The pollution was measured in a scientific way. The Indian lab brought the findings to India’s Supreme Court. This time the government listened. In 2007, India’s prime minister met with Dr. Mishra. A year later, Mishra heard what he called “the best news in 20 years.” The government was agreeing to support a pilot program of his plan in Varanasi. If it worked there, it could be put into effect all along the Ganges. The Ganges’ story is not over. Time will tell whether it is too late to restore India’s sacred river. But Dr. Mishra seems to have no doubts. As he confidently puts it, “Mother Ganges will help me to save her.”