Pygmalion review from 1938

advertisement

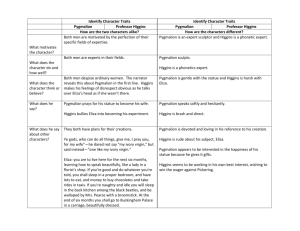

Movie Review Pygmalion (1938) By Frank S. Nugent Published: December 8, 1938 To put a completely straight face upon the matter, Pygmalion, which had its premiere at the Astor last night, marks the debut of a promising screenwriter, George Bernard Shaw. This Mr. Shaw, for many years identified with the legitimate theater, the rotogravure section, and the Letters-to-the-Editor columns, appears to have had little difficulty adapting himself to the strange new medium of the cinema. The difficulty, in fact, may be in the cinema's adapting itself to Mr. Shaw. His jocular boast, in the jocular preface to his picture, is that he intends to teach America what a "film should be like." But that sounds more revolutionary than it is; it is as optimistic as his wish that everyone see Pygmalion at least twenty times. Mr. Shaw is not revolutionizing the cinema in Pygmalion any more than he revolutionized the theater when he first put his comedy on in London in 1914. It caused a "bloody" scandal then, but Mrs. Pat Campbell and Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree were able to ride over it. The film version is no more startling, providing you keep a straight face upon the matter, for the camera is frequently flushing a covey of actors from a conversational thicket and Mr. Shaw sometimes is caught chuckling so hard behind his whiskers that it isn't quite clear what has been making him laugh. All this, of course, providing one keeps a straight face upon the matter. But Pygmalion is not a comedy for straight faces, and anyone who puts one on at the Astor should have his theater-going credentials examined and his sense of humor sent off for repairs. In the Shaw repertory, it is not one of the major items, so need not be taken too seriously. Taken lightly, as befits it, the comedy trips light from the tongue of any troupe—stage or screen— which has the grace to memorize its lines, to say them well and with appropriate gesture, while a good director clears or clutters up his sets and adds the precious element of timing. In each of these rather statistical particulars, Mr. Shaw's first film has been most happily served—although we reserve the right to enter a qualifier or two later. His story of a modern Pygmalion, a phonetics expert named Henry Higgins, who molds the common clay of Eliza Doolittle, cockney flower girl, into a personage fit to meet an Archduchess at an embassy ball, has been deftly, joyously told upon the screen. That instinct for comedy might have been expected of a Higgins by Leslie Howard, or a dustman by Wilfrid Lawson, or a Mrs. Higgins by Marie Lohr. It comes almost more satisfyingly, since unexpected, in the magnificent Eliza of Wendy Hiller. Miss Hiller is a Discovery. (She deserves the capital.) We cannot believe that even Mr. Shaw could find a flaw in her performance of Pygmalion's guttersnipe Galatea. Eliza is the bedraggled cabbage leaf gruff Professor Higgins takes into his home, feeds, clothes, batches (by proxy, of course), and teaches so that she can pass for a gentlewoman at the embassy ball and thereby win his wager. And as Eliza, who progresses from the "Garn, I'm a good girl, I am" days to those poignant ones when she is cat-clawing at her creator's eyes, Miss Hiller is so perfectly right that we wonder how either Mrs. Pat Campbell or Lynn Fontanne (of the Theatre Guild production) could have touched her. The picture has rung a few changes on the play. The embassy ball is a new sequence, instead of an off-stage incident, and has been worked with suspense, comedy, and fresh dramatic interest. The Dustman is not entirely the towering comic figure he was. His plaintive speech about being the victim of middle-class morality has been retained, naturally; but they lopped him off a trifle at the end. Professor Higgins's methods of phonetics instruction are added comic devices, and the scene at the Higgins tea party, when Eliza is getting a dress rehearsal for her social debut, has been enriched by some added Shavian dialogue. "In Hampshire, Hereford, and Hartford, hurricanes rarely ever happen," says Eliza dutifully, hitting her "h's" carefully. That is just before she starts telling about her aunt who drank gin like mother's milk and was "done in" by the fond folks at 'ome. Mr. Shaw truly has taught the American filmmakers something. He is showing them how valuable a writer can be, how unnecessary it is to drape romantic cupids over a theater's marquee, how wise it is to permit a leading man an occasional session of cruelly masculine ranting. But he must learn, too, not to let his cameras freeze too often upon a static scene. And he might have improved upon the film's conclusion—just as he might have bettered that of the play. But that's beside the point, which is that Pygmalion is good Shaw and a grand show. PYGMALION (MOVIE) Directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard; written by George Bernard Shaw, W. P. Lipscomb, Cecil Lewis, Ian Dalrymple, and Mr. Asquith, based on the play by Mr. Shaw; cinematographer, Harry Stradling; edited by David Lean; music by Arthur Honegger; art designer, Laurence Irving; produced by Gabriel Pascal; released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Black and white. Running time: 96 minutes.