Religious language Revision powerpoint Transcript

advertisement

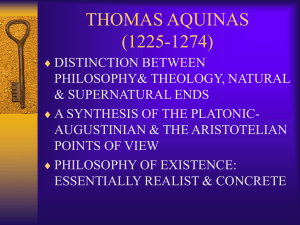

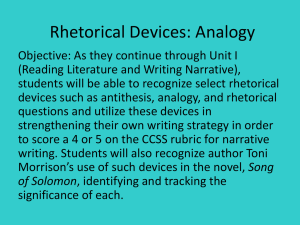

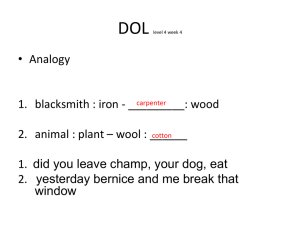

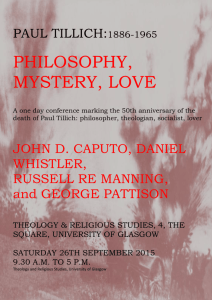

• Religious Language • Your A2 Topic Has Two Aspects: • Verification and Falsification. Some philosophers (particularly Logical Positivists) argue that religious language is meaningless because it cannot be verified or falsified (shown to be true or false). • ourselves, or (b) subject the hypothesis to any new or further forms of testing. Perhaps a lot of what we take for knowledge defies strict verification. Symbol and Analogy. Some philosophers argue that there may be meaning in religious language because it is symbolic (Paul Tillich) or because we can draw analogies between God and other things/properties (Thomas Aquinas). • Some key figures … • What’s the Problem? • Cognitivism and Non-Cognitivism • A major philosophical distinction in language is made between language which expresses knowledge and language which does not. • Cognitive Language expresses facts and knowledge (e.g. Dr. Williams teaches at Wellington College). • Non-Cognitive Language expresses things which we could never know: feelings, values, and (perhaps) metaphysical claims (e.g. Dr. Williams is worth listening too: teachers are a noble breed). • Critics of religion might emphasise the Non-Cognitive nature of much religious language. • First Problem: Verification and Falsification, the Logical Positivists • Formalising the argument: A.J. Ayer • A Problem in Verification • However, the idea of a Verification Principle entails a number of serious problems. How much can we really verify? For example: did King Harold die at the battle of Hastings? We can look at some historical records which say he did, but we cannot (a) observe it 1 • Some Criticisms of Verification • John Hick has criticised Ayer, suggesting that talk of God might be verifiable in principle. Convincing evidence is not apparent now, but it could be in the future; the whole idea of final judgement implies that God will be seen and known. • Richard Swinburne argues that there are propositions which no-one knows how to verify but still are not meaningless. He gives the example of toys which come out of their cupboard at night and dance around, then returning without a trace. No observation could ever establish this as truth, but it’s not meaningless. • The Verification Principle might contradict itself. The claim that a statement is only meaningful if it can be verified analytically or synthetically cannot itself be verified analytically or synthetically. Is the Verification Principle meaningless? • Falsification: Anthony Flew • This is the inverse of verification; Flew claimed that any positive claim we make also assumes that we deny its negation. If I say that College work is fun, I am also saying that College work is not, not fun. • Flew argued that language is only meaningful if we can conceive of some evidence which might count against it. It’s only meaningful to say that College work is fun because students might be able to show contradictory information: boring research projects, or a limited syllabus. • The problem with ‘God talk’ is that it often implies that it could never by falsified: “I know that God loves me in a special and mysterious way which noone may question or disprove”. If God is just a mystery, then we are not using language in a constructive, meaningful way. • Responding to Falsification • The philosopher R.M. Hare took up the idea of falsification and used it to describe certain beliefs which he called ‘bliks’. A blik is a non-rational belief which could never be falsified (disproved). For example, let us say that a student is convinced that his philosophy teacher is trying to kill him but, as his friends point out, there’s no evidence at all that this is the case. The student may say that this teacher is so clever that he would never leave any evidence of any kind. Bliks are not necessarily untrue (some are sane and some insane), but they are groundless. • 3) Evaluation of Verification – your views, criticisms of Verification: Hick, Swinburne, self-contradictory? 4) Falsification – Flew, Hare and the bliks. 5) Evaluation of Falsification – Hick, Mitchell and the freedom fighter. 6) Conclusion – consider and answer: is religious language meaningless? Is it non-cognitive? Does language even have to be verifiable to be meaningful? How might this impact on religion? Clear answers and strong argument throughout! John Hick responds by arguing that there are reasons behind religious beliefs: experiences, Scripture, etc. He also objects that there is no way to distinguish between sane or insane bliks, and the judgement that religion is insane could only ever be arbitrary. • Basil Mitchell’s Objection to Falsification • Finally, Basil Mitchell objects to the idea that religious claims are groundless ‘bliks’. He argues that religious claims are grounded in some facts and that the faithful do allow that evidence may stand against what they believe. They recognise, for example, the problem of evil. However, they do not allow that belief can or should be verified in a simple manner. • Mitchell draws a parable of a man claiming to be the leader of a resistance movement – it seems that he supports the fight but sometimes seems to help the enemy. One could choose to trust him despite the contrary evidence. So with God: one could trust in God while recognising the contrary evidence: that he allows evil and suffering, or disbelief. • Suggested Essay Structure - Paragraphs • Second Issue: Analogy and Symbol • The other area or problem on which you tend to get exam questions is analogy and/or symbol. These could be asked separately or together, or as part of a general question on religious language. So, it’s important to learn it all! • Essentially, we are now looking at attempts to say that religious language can be used meaningfully, only not in a direct or simplistically descriptive sense. Philosophers like Aquinas and Tillich try to show how our language might relate to God. • Aquinas: Why Analogy? • Thomas Aquinas was concerned by the problem of explaining God in human language; God is supposedly perfect and infinite, so he might defy description. • Aquinas stated that we could not speak of God ‘univocally’ (with our language being applied to him with the same meaning), but nor could we speak of him ‘equivocally’ (with our language being applied with a different meaning). This left Aquinas needing to find a way of using language as an indirect description of God. • For this he turned to ‘analogy’. An analogy is an attempt to explain the meaning of something by comparison with an example more familiar to us. • Analogy of Attribution 1) Introduction – basic problem, background, cognitive and non-cognitive language. 2) Verification – Logical positivists, Ayer and the VP, and the weak VP. 2 • • • There are three forms of analogy described by Aquinas: attribution, proper proportion, and improper proportion. The first of these (attribution) is dead easy. Aquinas thought that we could gain understanding of God by considering his role as creator. Simply, if God made the world then we could expect the world to reflect God in some way. So, we would be justified in drawing analogies between the world and God. Aquinas also explains this by the example of a bull and its urine. The health of the animal is present in its urine; we can tell that the bull is healthy by studying this. However, the health of the bull is only complete in the bull itself. So, what the urine tells us is indirect and incomplete. So too with God: what the world tells us of his goodness is meaningful, but it is also limited. • That gives us the order of reference – God’s goodness is foremost, because he is the source of this quality. The world has goodness only in a secondary respect. • Analogy of Proper Proportion • Here, John Hick takes on and develops Aquinas’ views. The basic idea is that humans possess God’s qualities because we are created in his image (Genesis 2). Yet, because God is perfect, we have his qualities in a lesser proportion. • • qualities for the sake of a loose comparison. Hick explains this by giving the example of faithfulness. Humans can be faithful to each other, in speech and behaviour, and so on. Dogs too can be faithful, but there is a great difference between this quality in a person and in an animal. Yet, there has to be a reasonable similarity, or we would not recognise dogs as faithful. So, there is “a dim and imperfect likeness” in the dog, as there is between us and God. An analogy which is just a metaphor and does not really deal with proportionate qualities would be one of improper proportion. For instance, ‘God is a rock’. This ignores essential differences in 3 • Criticisms of Analogy • We could criticise Aquinas’ claims about proportionate analogy, since we may dispute whether humans really were created “in the image and likeness of God”. This is challenged by Darwin’s theory of evolution and rejected by atheist Richard Dawkins. • We might wonder whether the evil in our world is also an analogy to God – this might make a perfectly good God impossible. However, a theodicy (such as Augustine’s) could resolve this problem. • We could also criticise analogy from the standpoint of verification, since the object we are drawing an analogy to (God) cannot be verified. However, for this we can refer back to criticisms of verification. • Richard Swinburne criticises Aquinas for producing an unnecessary theory. He claims that we can speak of God and humans as ‘good’ univocally, it is just that God and humans possess goodness in different ways. It is still the same essential quality, even though God is perfect and humans are not. • Religious Language as Symbolic • Theologian Paul Tillich took a different approach in attempting to show that religious language can be meaningful. He focused on the manner in which symbols may effect humans. • Tillich’s first main point is that symbols are not signs. Both of these point to something beyond themselves, but only symbols ‘participate’ in what they point to. For instance, a road sign just points to a fact about a road, whereas a symbolic flag participates in the power of the king or the nation. • Tillich goes on to number four key features of symbols: (a) They point to something beyond themselves, (b) They participate in that to which they point, (c) They open up levels of reality which otherwise are closed to us, and (d) They open up dimensions of the soul which correspond to those aspects of reality. • To explain (c) and (d), Tillich compared this symbolic language to a great work of art … • Criticisms of Tillich and Symbol • A number of criticisms could be levelled at what Tillich has put forward. Firstly, John Hick has argued that the idea of ‘participating’ in a symbol is unclear. Take the flag example; in what sense does this really do something? Is there really a big difference from signs here? • William Alston has objected that symbolism means that “there is no point trying to determine whether the statement is true or false”. Since Tillich’s symbols are not literally true, Alston feels that they could have no meaningful impact on us. They could not send us to heaven or hell, for example. • He then went on to say that problems in philosophy may occur through misunderstanding that words can be used in different language games. • For Wittgenstein, meaning is all about observing convention – just like in a game. There’s a right way and a wrong way to do things. • So with religion – there might be conventional or unconventional ways to talk about God. • Language Games and Religion • The theory of language games could be important because of the connection it makes with the ‘coherence theory of truth’. This is the view that statements are true if they fit with other statements and beliefs which are internally consistent. • One could argue that the ‘game’ of religious language cannot be criticised because internally it is coherent and intelligible. Religious views fit with other religious views. Perhaps religion is just a ‘language game’, and it will all make sense if we just participate. • Wittgenstein and Language Games • Finally, another area you might be asked to discuss is that of ‘Language Games’. • Much later in his career, years after he had influenced the Logical Positivists, Ludwig Wittgenstein changed his views on how language works. • The danger of this is that it could be too relativistic, allowing that any claims are equally valid. It also doesn’t explain how we could challenge truth claims. • In his Philosophical Investigations (published after his death), Wittgenstein focussed on the uses language can be put to. Famously, he wrote: “Don’t’ ask me for the meaning, ask for the use.” So, he was less concerned with the truth or falsity of language (contrast the Logical Positivists). • Also, it’s not quite clear whether Wittgenstein thought of religion as a ‘language game’. He had a certain respect for religion, but wrote little about it himself. • Some points to think about: • Does language work in a game? Can you give examples? • Is what Wittgenstein says at all comparable to Aquinas or Tillich? • Is religion another ‘language game’? • Is Wittgenstein’s later view right: is the use of language more fundamental than meaning? • For religious language, he thought that function might be more important than meaning. • Language Games • Wittgenstein argued that language works through a series of ‘language games’. That is, meaning only comes out of context; we have to know what ‘game’ that our terms are participating in. 4