Hinst for parent of origin effects detected in Inflammatory Bowel

advertisement

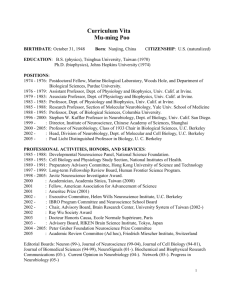

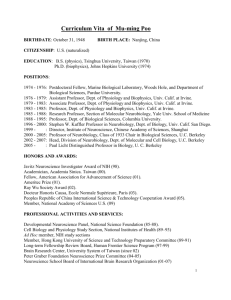

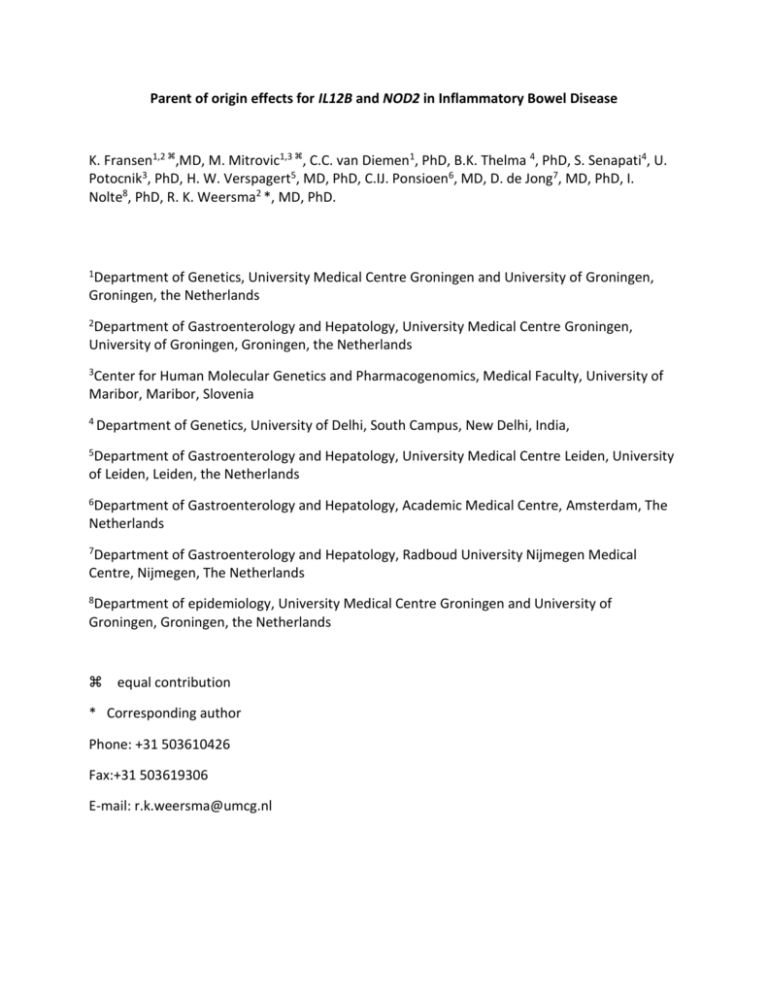

Parent of origin effects for IL12B and NOD2 in Inflammatory Bowel Disease K. Fransen1,2 ,MD, M. Mitrovic1,3 , C.C. van Diemen1, PhD, B.K. Thelma 4, PhD, S. Senapati4, U. Potocnik3, PhD, H. W. Verspagert5, MD, PhD, C.IJ. Ponsioen6, MD, D. de Jong7, MD, PhD, I. Nolte8, PhD, R. K. Weersma2 *, MD, PhD. 1Department of Genetics, University Medical Centre Groningen and University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands 2Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Medical Centre Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands 3Center for Human Molecular Genetics and Pharmacogenomics, Medical Faculty, University of Maribor, Maribor, Slovenia 4 Department of Genetics, University of Delhi, South Campus, New Delhi, India, 5Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Medical Centre Leiden, University of Leiden, Leiden, the Netherlands 6Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 7Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands 8Department of epidemiology, University Medical Centre Groningen and University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands equal contribution * Corresponding author Phone: +31 503610426 Fax:+31 503619306 E-mail: r.k.weersma@umcg.nl Abstract Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for the two main forms of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) have identified 99 independent susceptibility loci explaining ~23% of the total genetic risk for IBD. In the post-GWAS era the challenge is to uncover the remaining so-called hidden heritability. One of the sources might be a parent of origin (POO) dependent risk per allele, named genomic imprinting. This is characterized by a consecutive activation or inactivation of one of the copies of an allele depending on the parent from which it is inherited. An epidemiological study has shown that children from mothers with CD more often get CD than children from fathers with CD, indicating the existence of such a POO effect. We are the first to test for POO effects in IBD. For DNA genotyping we used a custom-made chip, the immunochip, which contains a dense map of ~180 immune disease related loci and ~200.000 variants. In a case-control study of 1367 cases and 2098 controls of Dutch ancestry we confirmed the association of 19 of the 99 known IBD loci (p value<0.001). To test for POO effects we used a recently developed POO-likelihoodratio model that proved successful in determining a PPO effect in type I diabetes. For this study, we tested the 28 loci that are associated with both CD and UC in 187 Dutch child parent trios in which the child suffers from either UC or CD. Additionally, we tested the three known NOD2 variants in CD trios and the UC gene BTNL2 in UC trios, since this gene is already known to be imprinted. In the analysis of the Dutch trios a significant POO effect in the IL12B locus was found (P= 0.019 OR=3.2). In the NOD2 locus the reported frame-shift mutation (rs2066847) showed a POO effect (p=0.013 OR=21.0). No significant POO effects were detected in the BTNL2 locus. Conclusions: Very little is known on the effect of genomic imprinting in complex diseases like IBD. Here we show for the first time that there is a POO effect for IL12B and NOD2 in the Dutch population. In the post GWAS era it is of utmost importance to study new sources to identify the hidden heritability. Follow-up studies with bigger cohort sizes and preferably including different ethnicities are necessary to confirm our findings and unravel the observed maternal imprinting in IBD. Currently we are analyzing a cohort of trios of Indian descent. We will test POO effects of 11 shared risk loci between Indian UC and Caucasian UC cases.