File

advertisement

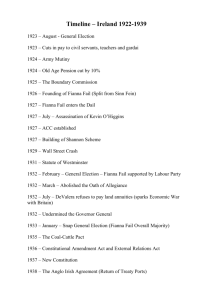

Fianna Fail’s Economic PoliciEs 1932–1939 Ireland’s economic problems proved just as difficult for Fianna Fail to solve as they had done for Cumann na nGaedheal. The difficulties arising from partition, lack of raw materials, limited markets and high competition remained, while national and world depression only served to further aggravate things. Fianna Fail’s solution was based on the acceptance of protectionism and the ideal of national self-sufficiency. This, they argued, would generate enough economic growth to lift the country out of the depression. It was fortunate that such policies were becoming acceptable in the fight against depression, now worldwide since the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Yet any real advance in the economic life of the country was, as always, bound up with agriculture. And in 1932, Irish agriculture was certainly in need of stimulation. The Minister responsible for those was Dr James Ryan. The tillage agricultural areas of the 26 counties were just less than 12 million acres. Of this 12% was given to tillage, 20% hay and 68% pasture. Farms also tended to be rather small – 58% of holdings under 30 acres. At the same time most farms were family run. Paid employees amounted to only 19% of the agricultural labour force. Fianna Fail sought to rectify the situation and chose as its main aims the encouragement of a return to tillage, the break-up of the large ranch-type farms, and the increase in size of most of the existing holdings. In order to do this the powers of the Land Commission would be widened and education and marketing opportunities would be improved. One final aim of the de Valera government in the area of agriculture was their desire to discontinue the payment of land annuities to Britain. The Land Annuities were the repayments to Britain of loans advanced to Irish farmers under the various land acts since 1885. Such payments amounted to £3 million per year, but on coming to power in 1932, de Valera insisted that the Irish government would retain all future payments. Arguments put forwards against payment included: 1. The 1923 and 1926 financial agreements had not been ratified by the Dáil and were therefore not binding. 2. The Northern Ireland government had been allowed to keep the land annuity payments as ‘free gift’. So why not the Southern government? 3. The Depression meant that the money was needed at home if any sort of economic recovery was to be made possible. De Valera’s decision inevitably angered Britain who imposed a 20% tax on Irish cattle and other agricultural exports to Britain. Ireland retaliated by imposing a 5% tax on goods imported from England to Ireland. Thus began the Economic War which proved disastrous for Ireland. Not only did it mean serious depression in agriculture but it also led to almost complete destruction of the cattle industry. Cattle exports to Britain fell from 750,000 in 1930 to 500,000 in 1934. The incomes of farmers deceased while unemployment and emigration increased. In fact, by 1935, Irish agricultural exports to Britain amounted to only £13.9m. In such a situation selfsufficiency became less a policy of economic advance and more a rescue operation. Subsidies were placed on wheat in an effort to encourage a switch to tillage. Farming. Yet although there was a dramatic increase in wheat production from 24,000 acres in 1932 to 254,000 by 1936 and sugar beet also expanded, there was only a 10% increase in crop production overall. The slaughter of cattle and the distribution of free meat were intended not only to discourage pasture farming but also to help those families in dire need. Government spending on agriculture inevitably rose during the Economic War, while the protection of bacon, flour, sugar and other food items from foreign competition caused them to increase in price. Thus, it was that all sectors, but particularly the poor and unemployed, were badly hit. De Valera countered opposition by maintaining that ‘if there are to be hair-shirts at all, it will be hair-shirts all round’. However, while the damage caused to Ireland was clearly great, Britain too suffered. British industry could ill afford to lose its best customer, particularly at the height of the Great Depression. In Ireland, meanwhile, anti-British sentiment was well expressed in the slogan ‘Burn everything British but their coal’. Ireland was also actively considering importing continental coal from places such as Germany and Poland. The sense of urgency thus felt by both sides, coupled with the good working relationship between Sir Warren Fisher (Secretary to the British Treasury) and J.W. Dulanty (Irish Commissioner in London) led to the first easing of tensions in the Economic War. This came in the form of the Coal-Cattle Pact of 1935. The British government agreed to increase the quota of imported Irish cattle by one third, in return for which the Free State undertook to buy its coal from Britain. Thereafter, signs became even more hopeful. This was largely thanks to the worsening international situation and the general policy of appeasement. In order to bring the Economic War to an end, the Irish delegation met with a British delegation in London over a 14 week period. The result was the Anglo-Irish Agreement, April 1938. The Irish delegation was led by de Valera who made it clear that the topics on the agenda were partition, defence, and the disputed repayments. Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister, refused to compromise on the question of partition, believing it to be ultimately a matter for amicable settlement between Ulster and the South. Yet De Valera did manage to secure the unconditional return of the Treaty Ports – Cobh, Berehaven, and Lough Swilly -. This was seen as ‘a wonderful triumph’, furthering, as it did, the concept of Irish independence and paving the way for Irish neutrality during the Second World War (1939-45). The financial arrangement which ended the war can also be seen as a victory for de Valera. Ireland was to pay £10 million as a final settle of all outstanding claims between the two countries. At the same time, the special duties or tariffs, imposed by both sides since 1932 were removed. While this agreement paved the way for increased economic prosperity, the outbreak of the second World War in 1939 prevented this and introduced a period of rationing which continued on into the post war years The world depression and the Economic War with Britain made the task of industrialisation much harder than it might otherwise have been. But Fianna Fail regarded industrial development as crucial to economic success. De Valera appointed Sean Lemass as Minister for Industry and Commerce. Under Leamass the range and scope of State Sponsored Bodies became wider. In all, 13 Semi-State Companies were set up to seal with a wide range of industries and services. The Industrial Credit Corporation was established in 1933 by Lemass. It sought to advance loans with which to found new industries, Aer Lingus, Aer Rianth, the Turf Development Board (later Bord na Mona), the Dairy Disposal Company, and the Irish Life Assurance Company were also set up. These semi-states were given monopolies on the supply of particular items in Ireland. The absence of competition meant that prices were allowed to rise even when quality fell, the cost of which was carried by the consumer. Non-trading enterprises of the same period include Bord Failte, the Hospital Trust Board and the Medical Research Council. Lemass also introduced the Control of Manufacturers Acts in 1932 and 1934 which decreed that some Irish nationals must be involved in all new firms. This was to ensure that new Companies would not be foreign-owned and controlled, but the rule was often broken and ‘token’ Irishmen were not uncommon on the board of British Controlled businesses., At the same time, further employment was crated by a massive slum clearance programme, the construction of new factories and the building and renovation of 132,000 houses, Priority was placed on manufacturing and service industries. Overall between 1932 and 1939 the value of net industrial output rose from £25.6m to £36m, while industrial employment went up from 111,000 to 166,000. There was, however, a price for this achievement. Tariffs and quotas were introduced by Fianna Fail to protect industries and to safeguard home market. The first budget, March 1932 for example contained no less than 43 new duties. This policy was continued over the years, more than 1000 items being affected by 1936. While this did offer protection to smaller industries and encouraged new companies to be set up (textiles, footwear, cutlery, ropes cement and others) these new industries had neither the capacity not the will to export their produce. As for the larger companies, these were not helped, depending as they did on the export market. Guinness managed to solve this in part by developing their Park Royal Brewery near London. Nonetheless, the amounts earned by the export of biscuits, porter and beer fell sharply in the 30s. Indeed there was a marked decline in the whole total of non-agricultural exports while the value of imports (other than food studs) rose. Further difficulties included the fact that incomes remained low and poverty was widespread. In a general sense, therefore, economic problems were only slightly, if at all, eased during the period in question. Fianna Fail accompanied its agricultural and industrial policies with a social policy, the aim of which was to help the disadvantaged and less fortunate members of society. The Unemployment Assistance Act of 1933 for example, increased unemployment benefits and extend them to small farmers and farm labourers In that same year, the National Health Act sought to improve the provision of health insurance, Old Age and Blind Pensions were improved while in 1935, pensions for widows and orphans were introduced. The State also intervened in the area of housing and the Housing Act of 1932 allowed for the State to contribute form one third to two thirds of housing schemes created by the local authorities. Up to March 1937, £3.4m had been used for this purpose and a further £6, was ear-marked for the future. Thus it was that in the 1930s, there as an average of 12,000 houses built per year in comparison with 2,000 per year in the 1920s. Yet while Fianna Fail’s social policy was undoubtedly more generous than that of Cumann na nGaedheal, poverty remained widespread. In real terms, Irish people were comparatively worse off as, by 1931, the average Irish income was 60% of the British average by 1939 this was down to 49%. However the effect on the economy of the Economic War and the World Depression must be borne in mind when assessing the overall saturation.