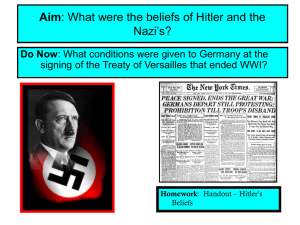

The Collapse & Recovery of Europe (1914-1970s)

advertisement