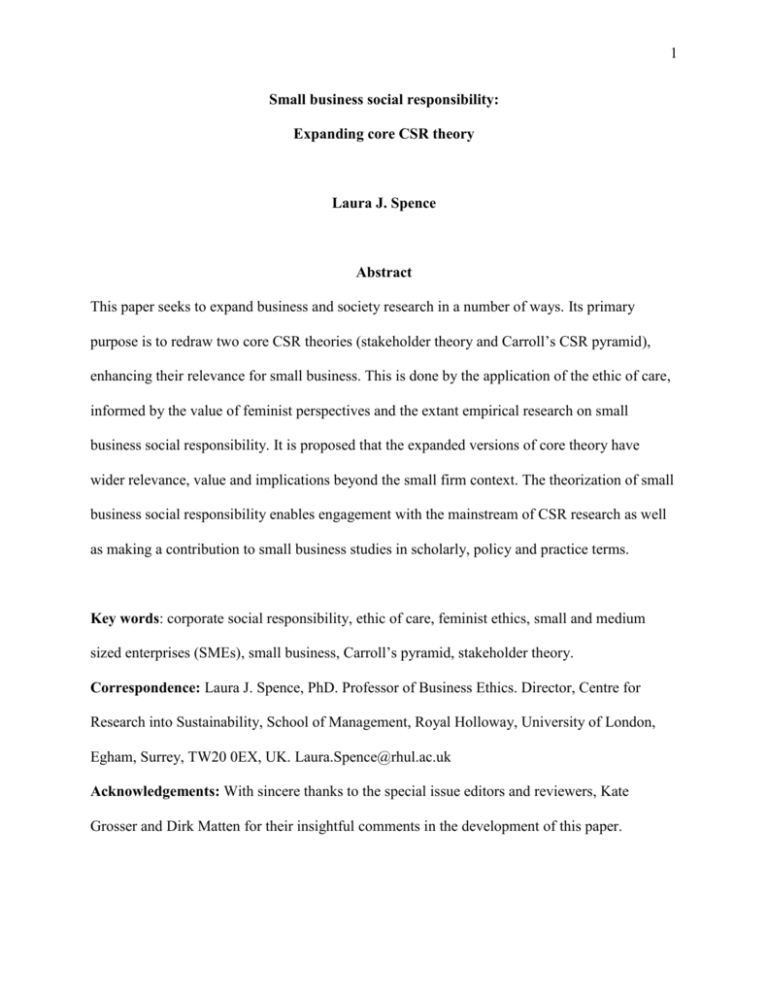

Small Business Ethics

advertisement