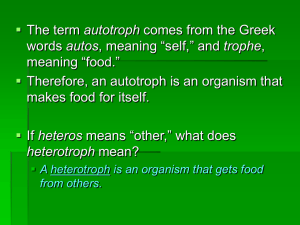

Low phosphate levels and poor nutritional status * is there a link

advertisement

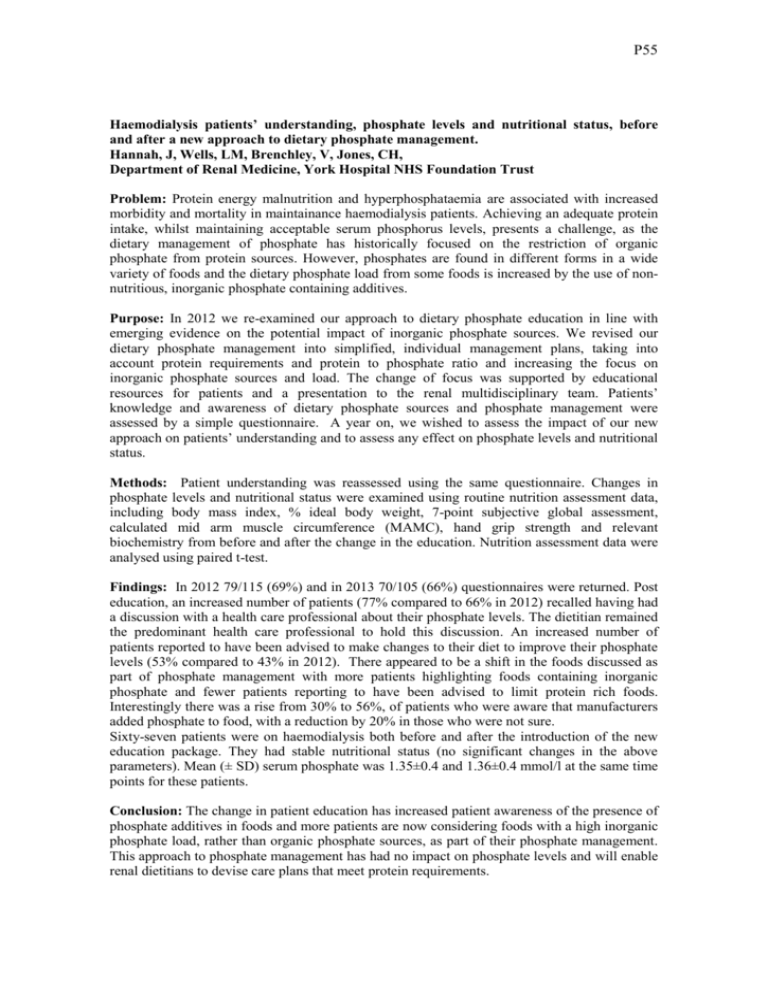

P55 Haemodialysis patients’ understanding, phosphate levels and nutritional status, before and after a new approach to dietary phosphate management. Hannah, J, Wells, LM, Brenchley, V, Jones, CH, Department of Renal Medicine, York Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Problem: Protein energy malnutrition and hyperphosphataemia are associated with increased morbidity and mortality in maintainance haemodialysis patients. Achieving an adequate protein intake, whilst maintaining acceptable serum phosphorus levels, presents a challenge, as the dietary management of phosphate has historically focused on the restriction of organic phosphate from protein sources. However, phosphates are found in different forms in a wide variety of foods and the dietary phosphate load from some foods is increased by the use of nonnutritious, inorganic phosphate containing additives. Purpose: In 2012 we re-examined our approach to dietary phosphate education in line with emerging evidence on the potential impact of inorganic phosphate sources. We revised our dietary phosphate management into simplified, individual management plans, taking into account protein requirements and protein to phosphate ratio and increasing the focus on inorganic phosphate sources and load. The change of focus was supported by educational resources for patients and a presentation to the renal multidisciplinary team. Patients’ knowledge and awareness of dietary phosphate sources and phosphate management were assessed by a simple questionnaire. A year on, we wished to assess the impact of our new approach on patients’ understanding and to assess any effect on phosphate levels and nutritional status. Methods: Patient understanding was reassessed using the same questionnaire. Changes in phosphate levels and nutritional status were examined using routine nutrition assessment data, including body mass index, % ideal body weight, 7-point subjective global assessment, calculated mid arm muscle circumference (MAMC), hand grip strength and relevant biochemistry from before and after the change in the education. Nutrition assessment data were analysed using paired t-test. Findings: In 2012 79/115 (69%) and in 2013 70/105 (66%) questionnaires were returned. Post education, an increased number of patients (77% compared to 66% in 2012) recalled having had a discussion with a health care professional about their phosphate levels. The dietitian remained the predominant health care professional to hold this discussion. An increased number of patients reported to have been advised to make changes to their diet to improve their phosphate levels (53% compared to 43% in 2012). There appeared to be a shift in the foods discussed as part of phosphate management with more patients highlighting foods containing inorganic phosphate and fewer patients reporting to have been advised to limit protein rich foods. Interestingly there was a rise from 30% to 56%, of patients who were aware that manufacturers added phosphate to food, with a reduction by 20% in those who were not sure. Sixty-seven patients were on haemodialysis both before and after the introduction of the new education package. They had stable nutritional status (no significant changes in the above parameters). Mean (± SD) serum phosphate was 1.35±0.4 and 1.36±0.4 mmol/l at the same time points for these patients. Conclusion: The change in patient education has increased patient awareness of the presence of phosphate additives in foods and more patients are now considering foods with a high inorganic phosphate load, rather than organic phosphate sources, as part of their phosphate management. This approach to phosphate management has had no impact on phosphate levels and will enable renal dietitians to devise care plans that meet protein requirements.