The Parties

advertisement

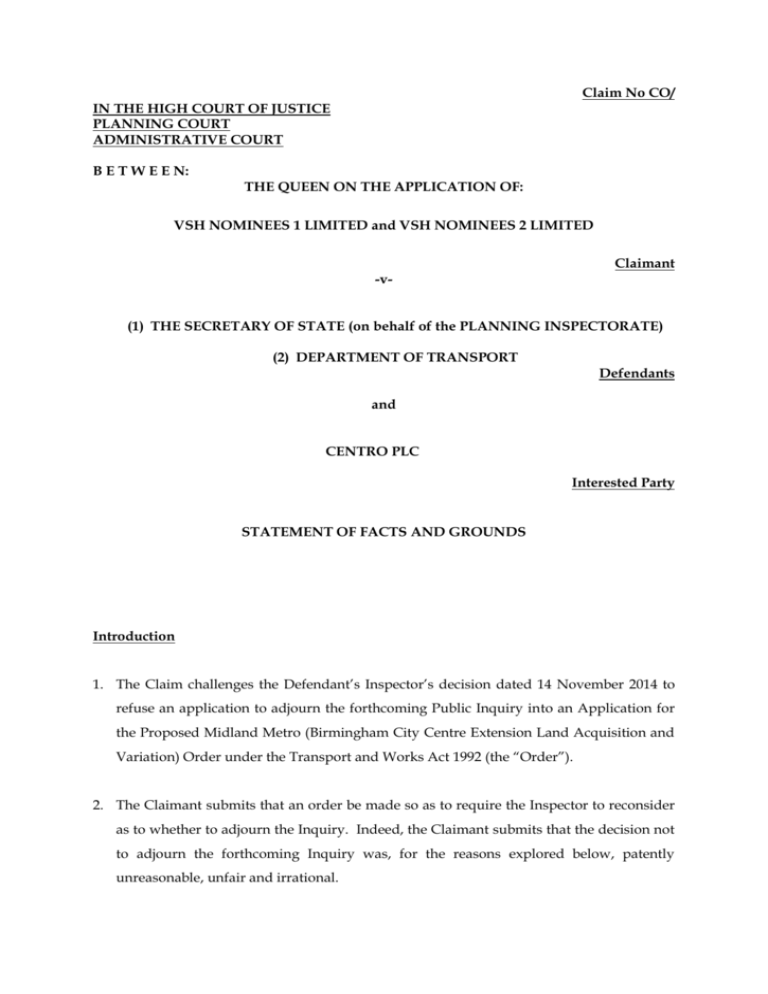

Claim No CO/ IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE PLANNING COURT ADMINISTRATIVE COURT B E T W E E N: THE QUEEN ON THE APPLICATION OF: VSH NOMINEES 1 LIMITED and VSH NOMINEES 2 LIMITED Claimant -v(1) THE SECRETARY OF STATE (on behalf of the PLANNING INSPECTORATE) (2) DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORT Defendants and CENTRO PLC Interested Party STATEMENT OF FACTS AND GROUNDS Introduction 1. The Claim challenges the Defendant’s Inspector’s decision dated 14 November 2014 to refuse an application to adjourn the forthcoming Public Inquiry into an Application for the Proposed Midland Metro (Birmingham City Centre Extension Land Acquisition and Variation) Order under the Transport and Works Act 1992 (the “Order”). 2. The Claimant submits that an order be made so as to require the Inspector to reconsider as to whether to adjourn the Inquiry. Indeed, the Claimant submits that the decision not to adjourn the forthcoming Inquiry was, for the reasons explored below, patently unreasonable, unfair and irrational. The Parties 3. As to the parties and their roles: a. The Claimant is VSH Nominee 1 Limited and VSH Nominee 2 Limited (together “VSH Nominees” or the Claimant). The Claimant is a statutory objector in relation to the Order. b. The Defendant is the Secretary of State on behalf of the Planning Inspectorate and the Department for Transport. c. The Interested Party is the Promoter of the Order. Background 4. Relevant background to this claim is set out in the Witness Statement of Michael Pocock, the Chronology and the correspondence bundle which accompany these grounds of challenge. 5. The scheme to which this Order relates involves the promotion of a tram line in central Birmingham. For present purposes, it is sufficient to emphasise a number of central points. a. The promotion of the scheme has a lengthy history. The specific issues of relevance date back to 1997 and the Secretary of State’s decision to accept the Inspector’s recommendation in 2004 (the “2004 Decision”). The 2004 Decision is of particular relevance because it was made on the basis of the prohibitive lack of feasibility and cost of various alternative routes. b. Material changes to the proposals have occurred since the 2004 Decision. There have been policy changes in terms of decision making; alterations to the alternative routes; other considerations in relation to the immediate property and the route’s effects on pedestrian. For example, the proposed trams are to be wider than examined previously as part of that decision. This will have a material impact on the proposed route given that certain streets (Pinfold Street as just one example) have some limited carrying capacity in terms of their restrictive width. A bus depot is also no longer in situ. c. The Claimant’s land and building is grade II listed. Its environs are of significant heritage importance given that it is the principal pedestrianised area in the locality that is immediately adjacent to a grade I listed building and is located in one conservation area and adjacent to another. Should there be genuine, feasible and affordable options that could avoid the need for those environs to be harmed (insofar as the previous Inspector found such harm to be outweighed by the lack of feasible alternatives) by the proposed route then there is a clear public interest in such alternatives being fully and properly considered. d. It is an essential part, indeed a requirement, of any such Inquiry relating to major schemes for alternative routes to be considered yet, to date, alternatives have only been considered in terms of minor alterations to the promoted route and discrete sections of that route. e. The promotion of the Order must necessarily fail unless and until alternative routes have been fully and properly reconsidered. The previous issues as to the economic viability, cost and effect of possible alternative routes both in terms of their potential effect on the Claimant’s building and also its immediate environs can be overcome through re-routing the proposed tram line away from Victoria Square. f. Given the passage of time since the 2004 Decision, and the substantial amount of new evidence that strongly suggests that a number of the assumptions and conclusions of the previous inspector are now insupportable, it is in the public interest for the scheme, and other alternative route options, to be reconsidered fully in light of the available evidence. Submissions 6. The Claimant’s position in relation the above has been consistent and repeatedly communicated to the Interested Party since before the submission and exchange of Statements of Case back in August 2014. The Claimant’s position has neither changed nor altered to any material extent that could be said to justify the Interested Party’s late and obstructive approach to exchange of evidence, information and documents. Effect upon land and building 7. The Order will cause harm to the Claimant’s building, land and its immediate environs. As noted above, such building, land and area are significant in terms of their heritage and contribution to the built environment of Birmingham City Centre. Indeed, the previous Inspector found that harm would be caused to Victoria Square and its environs (see, for example, para 6.14.3 of the 2004 Decision). 8. Given that the Claimant’s evidence explores the potential for an alternative route to avoid harm to the above assets, it is clearly in the public interest for such to be explored in full at the Inquiry. In view of the fact that it is claimed that the Claimant’s alternative route would also serve the city better in terms of connectivity and in planning terms, it would be unreasonable and/or irrational for the Inquiry to proceed in a manner that would obstruct and/or prevent such exploration from taking place. 9. Furthermore, even on the Interested Party’s own case, some minor alterations have been made to the previously proposed scheme (for example, how it transits through Victoria Square itself). The harm of such alterations must be fully and properly considered at Inquiry. Listing and timetabling 10. It is important to note the context in which preparation for the Inquiry has been undertaken and as a result of which the timetabling occurred. 11. The Inquiry was originally scheduled to last three days (19 November to 21 November inclusive). The Claimant instructed Leading Counsel on that basis. Numerous consultations have taken place between Leading Counsel, the Claimant and its expert advisors. Such timetabling occurred largely as a response to the scope of the Statements of Case submitted by the parties. The Interested Party’s Statement of Case failed to disclose, infer or intimate that it would be relying upon the copious amounts of information and documentation that has been disclosed on exchange of evidence and, in some instances, as late as 10 November 2014 (nine days before the Inquiry and on the final date when evidence could be served as rebuttal). This is clearly prejudicial to the Claimant and contrary to the spirit and intent of the extant inquiries procedure rules. 12. This prejudice is aptly described at paragraphs 17-19 of Michael Pocock’s witness statement, which explains that: a. Prior to receipt of the letter from the programme officer on 14 November 2014, the Claimant’s reasonable assumption was that it would make submissions to the Inspector at the inquiry opening on the 19 November 2014 on the basis that the evidence was largely unchallenged (save for the previous Inspector's conclusions on any written evidence previously considered). The Claimant was going to adopt the same position for the alternative routes. b. As to the CPO of Victoria Square House itself, the Claimant came to the conclusion (again on the basis of the Interested Party’s limited disclosure, evidence and Statement of Case) that the case was a relatively narrow one and related to the effects on the building and immediate environs of Victoria Square. The CPO had not had proper regard to the effects on Pinfold Street and there was no consideration of matters outside of the Variation Order although there was some consideration of Victoria Square. c. All of the above was a position that was rationally and reasonably held given that the Claimant only principally had one or two Gillespie drawings received from the Interested Party to base its position on (without any vertical alignment information). d. Therefore, the Claimant’s understanding was that evidentially the Inquiry would require three days. It was only following exchange of all the evidence that it became clear that the Interested Party was raising substantial new evidence and points in relation to, in particular: its business case, economics, value for money, alternatives, bridges and reports, some of which have still not been received (including that relating to the obtrusive effect upon the listed building and whether it is able to have fixing brackets attached to it). 13. The Inquiry now looks likely to run to around nine days with very significant amounts of new information, evidence and documentation that has been supplied in the manner described above. In particular in relation to the alternative and the evidence concerning the bridges some of which is still absent (including the 2004 evidence) as well as evidence contained in the business case in relation to potential further compulsory purchase of land as well as costings. For the Inspector to have refused to adjourn the Inquiry on the basis that any unfairness can be remedied as a result of the cross examination of the Interested Party’s witnesses fundamentally misunderstands and underestimates the level and nature of work that goes into preparation for such cross examination including briefing notes to counsel by witnesses, particularly when it relates, as it would in the present instance, to detailed and technical expert evidence. This is supported by paragraph 15 of Michael Pocock’s witness statement in which he explains that engineers would “usually quote six to eight weeks to undertake this work. Given the urgency in this matter, notwithstanding his other professional commitments, James Parsons has indicated that it may be possible to produce a draft report in three and a half weeks.” 14. Further to the above, the Inspector’s position is yet more unreasonable and irrational when one considers the fact that much of the recently disclosed documentation relies upon a number of other documents that the Claimant still does not have a copy of. This is perhaps best illustrated in relation to the fact that the scheme, both then and now, has been promoted on the basis that total reconstruction of a significant bridge would be required. That position appears to have been maintained in reliance upon a 2004 Report compiled by a bridge engineer, which the Claimant has still yet to be provided with. Preparation for the Inquiry 15. The Claimant has sought to prepare for the Inquiry in line with the relevant procedural timetable and extant inquiry procedure rules. The Claimant has acted in an open and transparent manner throughout, only requesting further information as and when it has been necessary to do so in the context of the compulsory purchase powers which are sought by the Interested Party. 16. In any event, the Claimant ought never to have been in the position of having to request crucial information a matter of weeks before the Inquiry opened as it should have been supplied earlier, in a timely manner and in the clear knowledge that an Inquiry had been requested by the promoter (and that there were outstanding objections including by the Claimant, whose Statement of Case they had in August as well as many requests for the same information concerning the alternative route and the bridges on Navigation Street). Whilst the 2005 Metro Scheme has statutory approval, the variation to that scheme does not and, additionally, the Interested Party’s compulsory purchase powers for the next phase of the scheme have expired. As such, the Claimant’s requests for further information have, at all times, been reasonable and proportionate to the exercise of the draconian powers of compulsory purchase. Furthermore, the Interested Party is under a legal obligation to make all information in connection with the proposal publicly available in any event in justification of its case. The application for an adjournment 17. The essence of the Claimant’s application for an adjournment of the Inquiry can be summarised very shortly: a. Not only has the Interested Party failed to disclose certain crucial documents (notwithstanding the Claimant’s detailed, timely and repeated requests) but also those documents that have been provided have frequently been provided in an inappropriate form, incomplete, or in a piecemeal fashion. b. Furthermore, the latest series of documents that have been produced are of a scale that is disproportionate and wholly unreasonable in the circumstances. 18. As to a. above: a. The correspondence accompanying these grounds reveals continued attempts on behalf of the Claimant to seek further highly relevant information and full disclosure of highly relevant documents from the Interested Party and other parties such as Network Rail and Birmingham City Council (as that was where the Claimant was directed by the Interested Party). Such attempts have included Freedom of Information and Access to Environmental Information requests that have been met with no cooperation on behalf of the Interested Party whatsoever. b. At no stage has the Interested Party, either through its Statement of Case or otherwise, intimated that such documents would be disclosed at such a late stage or that they existed or that they were in their possession or that they had access to them. c. Notwithstanding such lack of transparency, it now appears that the Interested Party did have access to those documents and relied upon them (and put in a one page extract from them in evidence) that were disclosed as late as 26 October 2014 and 10 November 2014 not only as part of its rebuttal to the Claimant’s evidence but also, and crucially, as part of its promotion of the Order. It is, therefore, inconceivable that the Interested Party cannot have been aware that such documents would require disclosure until such a late stage in the Inquiry preparation procedure. It is simply not sufficient for the Interested Party to suggest that because those documents are recent their obstructive manner is excused. 19. As to b. above: a. To take just one example, on exchange of evidence on 26 October 2014, the Claimant received a substantial quantity of new information not previously disclosed or referred to in the Interested Party’s Statement of Case and some but by no means all of the evidence requested by the Claimant. The new information included over 600 pages of the “Business Case”, which was not available on the Interested Party’s website and whose existence was not previously known of by the Claimant or even mentioned in discussions. b. Notwithstanding its late disclosure, the Interested Party must have known about the likely content of such information and documentation well in advance of 26 October 2014 (when the first tranche was disclosed) and 10 November 2014 (when an even later tranche was disclosed). c. Other new documents have included very detailed engineering documents in relation to which the Claimant must be provided an adequate and meaningful opportunity to seek and receive expert advice. This is particularly so given the central part that such documents will play in any meaningful testing of alternative options (and they are incomplete given that the 2004 report remains missing). d. Furthermore, now that the Interested Party has purported to disclose further documents, those documents are of such a size, detail and complexity that it is inconceivable to think that the Claimant will be in a position to fully and appropriately brief Leading Counsel (or indeed any counsel) in advance of the Inquiry. Sole objector 20. Throughout its preparation for the Inquiry the Claimant has had to attempt to hit a moving target. The importance of this is further emphasised by the fact that the Claimant is the sole objector to the Order. 21. It simply is not a response to such difficulties to say, as the Interested Party may attempt, that the Claimant ought to have known in the circumstances that such information was available and would be supplied in due course or that it is in the public interest for the Inquiry to continue. To accept such an argument would be to miss the essential unfairness that underpins this application. In the context of this matter, in which the Claimant is a statutory objector to an Order promoted by the Interested Party, it is clear that the prejudice that this has caused to the Claimant in its preparation for the Inquiry has been manifest and substantial. 22. Furthermore, given that the Claimant is the sole objector, the adjournment of the Inquiry would cause no prejudice to any third party. That much is plain. 23. It is also not an appropriate response to say that any unfairness caused by the late disclosure and exchange of key information will be remedied by the inquiry process and cross examination. In this instance, the Claimant’s role as sole objector means that cannot occur: there is no other objector that can be relied upon to test the Promoter’s evidence and/or the basis for its assumptions. 24. Given the very serious repercussions that the confirmation of the Order would have for the Claimant, it is unreasonable to expect the Claimant to instruct alternative Counsel even assuming one to be available1: a. This is a complex case with technical issues as to bridge design, alternative routes, planning, conservation, heritage and economic evidence. The Claimant instructed Leading Counsel on that basis. Numerous consultations have taken place between Leading Counsel, the Claimant and its expert advisors. To expect or consider that it would be possible to simply instruct alternative counsel at this late stage is plainly wrong. b. As noted above, the Inquiry was originally timetabled on the basis of three days. This was done as a result of the content of the parties’ Statements of Case. The Interested Party ought not to profit as a result of its own failure to appropriately refer to its intention to rely upon the documents, or essence of the documents, that it has only recently deigned to disclose. 25. Further to the above, to suggest that any consequent unfairness can simply be remedied through the process of cross examination2 is also plainly wrong. Indeed, for cross examination of the relevant witnesses and individuals to be of any worth whatsoever it is essential that the Claimant is: a. Given adequate time to analyse and consider this recently provided information particularly where, as is the case here, the Claimant’s requests for such information have repeatedly been ignored or passed over; and b. Provided with a meaningful opportunity to rebut such information and evidence through the submission of its own evidence if necessary. The Claimant’s Leading Counsel, John Steel QC, is not available during the weeks beginning 24 November 2014 and 1 December 2014 as he has other professional commitments, including a case in the High Court listed for the week beginning 24 November 2014 and a trial listed for 5 days starting on 1 December 2014. 2 As appears to be the suggestion made by the Programme Officer in the third paragraph of her letter dated 14 November 2014. 1 26. Notwithstanding that the Interested Party may attempt to characterise the difficulties outlined above as simply part and parcel of the preparation for an Inquiry3, the fact remains that for the Promoter of this Order to benefit from its own failure to intimate that it would seek to rely upon such information in its Statement of Case, to disclose relevant material promptly or in accordance with the rules of natural justice would be manifestly unreasonable and unfair. 27. Whilst it is clearly the case that professional witnesses are instructed on a fluid basis that may require further work from time to time, such witnesses also have numerous concurrent commitments. The purpose of a Statement of Case is to put another party on notice as to the case that they must meet. This is particularly important in the context of compulsory purchase where the repercussions of confirmation are so inherently serious. Had the Interested Party chosen to disclose its reliance upon such documents at the appropriate time and supplied the relevant information in a timely manner (which, on any basis, ought to have been well in advance of the actual disclosure of such documents), then the Claimant would have instructed its professional witnesses accordingly and would have informed the Planning Inspectorate had there been any problem. Again, an adjournment is the only fair and appropriate response to ensure that the Interested Party does not profit from its own failure to have done so. Summary of Grounds and Conclusions 28. In light of the background to both the promotion of the Order and, more specifically, the recent conduct in relation to the exchange of evidence and documents prior to the forthcoming Inquiry, the Claimant submits that the Inspector’s decision not to adjourn the Inquiry after the first day or at an appropriate moment (as communicated by letter dated 14 November 2014) was unreasonable, unfair and irrational. 29. The Claimant asserts that there are alternative route options that must be fully and properly considered at any Inquiry into the Order. Such options may represent better 3 See, for example, paragraph 11 of letter from Winckworth Sherwood dated 12 November 2014 which suggests that “VSH further seemingly complains that its witnesses have set aside insufficient time to consider Centro’s main and rebuttal evidence. Yet it is to be expected that experienced professionals will make due allowance for this, failing which they will not accept the instructions in the first place. Yet again this found no case for adjournment.” value for money (a key consideration given the Interested Party’s public funding), better connectivity, greater planning benefits and less harm to significant heritage and conservation assets. 30. For such alternatives not to be considered fully and properly solely because of the Interested Party’s failure to intimate and identify in its Statement of Case its intended reliance upon a sequence of documents that have been disclosed late (if at all) would be unreasonable, irrational and unfair. The prejudice that a refusal to adjourn the Inquiry would cause to the Claimant, and to the public interest, is manifest and substantial. Such prejudice would be occasioned not only in terms of the Claimant’s objection to the Order but also as to the promotion of alternative routes. 31. It simply is not a valid response to such concerns, or a reasonable position for the Inspector to adopt, to suggest that any such prejudice can be overcome by the inquiry process (including cross examination), the Claimant instructing alternative counsel or by any other means. It is plain that it cannot. 32. For the above and other reasons, the Claimant asks the Court to grant permission and to order that the Defendant’s inspector reconsider the decision not to adjourn the Inquiry. 33. In view of the urgency of this application, the Claimant may apply to amend its grounds of challenge in due course. JOHN STEEL QC JONATHAN DARBY 17 November 2014